A Cessna light aeroplane and a Tecnam microlight collided on final approach parallel runways at Masterton. Tecnam had right of way but Cessna pilot did not see Tecnam. Both pilots died. Pilots should always keep a lookout for other aircraft, listen out for radio calls, obey Civil Aviation Rules, and follow standard operating procedures. CAA and WorkSafe should work with aerodrome owners and operators to ensure that operators and managers of aerodromes receive appropriate training and support.

Executive summary Tuhinga whakarāpopoto

What happened

- On Sunday 16 June 2019, Tecnam P2002 ZK-WAK, a microlight two-seater aeroplane, was on a short local flight around Masterton with a pilot only on board. At the same time, Cessna 185A ZK-CBY, a light aeroplane, was being used for parachuting operations over Masterton Aerodrome.

- At 1112, both aeroplanes were preparing to land back at Masterton Aerodrome when they collided. The collision occurred as ZK-WAK was on the final approach to land on runway 06, the sealed main runway. Meanwhile ZK-CBY had completed its parachute drop and was turning onto the final approach to land on runway 06L, a parallel grass runway. ZK-CBY, the faster of the two aeroplanes, struck ZK-WAK’s right side as it approached from the right and behind.

- Both pilots were killed in the collision and both aeroplanes were destroyed.

Why it happened

- The pilot of ZK-CBY was joining the non-standard right-hand for runway 06L, as this was how they had been instructed to join. The pilot of ZK-CBY, as the joining aircraft, needed to give way to ZK-WAK, but did not see it in time to avoid the collision. The non-standard join was at variance with Civil Aviation Rules (CARs), but had become an accepted practice at the aerodrome. A recommendation was made about the need to address non-compliance and incident reporting, particularly at unattended aerodromes.

- Both aeroplanes were approaching the runways at the same time. The aerodrome chart informed pilots that ‘simultaneous operations’ were prohibited. However, there was no definition of what ‘simultaneous operations’ were, and as a result there were a range of interpretations. A recommendation was made to address this deficiency and review aerodrome charts generally to ensure they are relevant and consistent.

- The Commission has investigated two previous mid-air collisions that have occurred at unattended aerodromes – Paraparaumu in February 2008 and Feilding in July 2010. The investigation into the Masterton incident identified factors that were common to all three mid-air collisions, which included:

- the collisions occurred at unattended aerodromes

- each collision involved an aircraft that was re-joining

- the weather conditions on each occasion were good

- pilots made appropriate radio calls, updating the location and intentions

- all the pilots were familiar with the aerodrome and procedures

- each collision involved a pilot in one of the two aircraft who held a commercial pilot licence or higher qualification.

- As a result, the investigation found safety issues that were common to the three mid-air collisions, including:

- pilots not actively listening to the radio calls from other aircraft

- the adequacy of the training and support of aerodrome managers, especially at unattended aerodromes.

- There was insufficient evidence to determine the level of influence that weather, familiarity and pilot experience may have played as a common factor.

- Recommendations were made to address these deficiencies.

What we can learn

- Pilots, regardless of experience, need to maintain an effective lookout and proactively listen to the radio calls made from other aircraft. Pilots need to be aware of and comply with CARs and follow standard operating procedures.

- Aerodrome owners and operators, in conjunction with the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) and WorkSafe New Zealand, need to collectively ensure aerodrome operators and aerodrome managers are appropriately trained and supported.

Who may benefit

- All pilots, operators, aerodrome operators and aerodrome managers may benefit from the findings, recommendations and lessons in this report.

Factual information Pārongo pono

Narrative

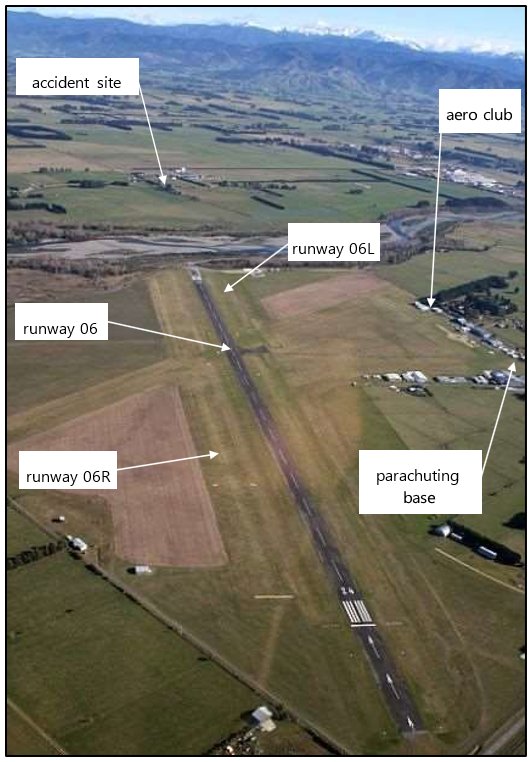

- On the morning of Sunday 16 June 2019, ZK-CBY, a Cessna 185A aeroplane was being used for parachuting at Masterton Aerodrome (known locally as Hood Aerodrome, located on the eastern outskirts of Masterton township). The weather conditions were suitable for parachuting with clear skies and little or no wind. The pilot of ZK-CBY completed one uneventful flight, taking off at 0944 and dropping a tandem pair and a single parachutist over the aerodrome before returning to land on runway 06L (runways are referenced to the nearest 10° magnetic bearing. Runway 06L was the left runway of three runways on a bearing of 060°. The other two runways were identified as 06 (sealed runway) and 06R (right)) at 1001. The pilot of ZK-CBY then shut down the aeroplane engine to allow time to prepare for the next load.

- At 1047:44(times indicate the commencement of each radio call), the pilot of ZK-CBY, after boarding the second load of parachutists and starting the engine, made a call on 119.1 megahertz (MHz), the local radio frequency, advising any other local traffic that ZK-CBY was taxiing for runway 06 (a radio call or broadcast would typically start with ”Masterton traffic” followed by aircraft callsign, location and intentions). At 1050:17, the pilot of ZK-CBY made a second radio call advising they were taking off from runway 06 and climbing to 13,000 feet (4000 metres) for parachuting over the aerodrome. Shortly after, at 1050:29, the pilot and only occupant of ZK-WAK, a Tecnam P2002 aeroplane, made a radio call on the same local frequency advising traffic it was taxiing to runway 06. The pilot of ZK-WRA, a second Tecnam aeroplane, then called advising it was operating four nautical miles (8 kilometres) east of the aerodrome at 3000 feet.

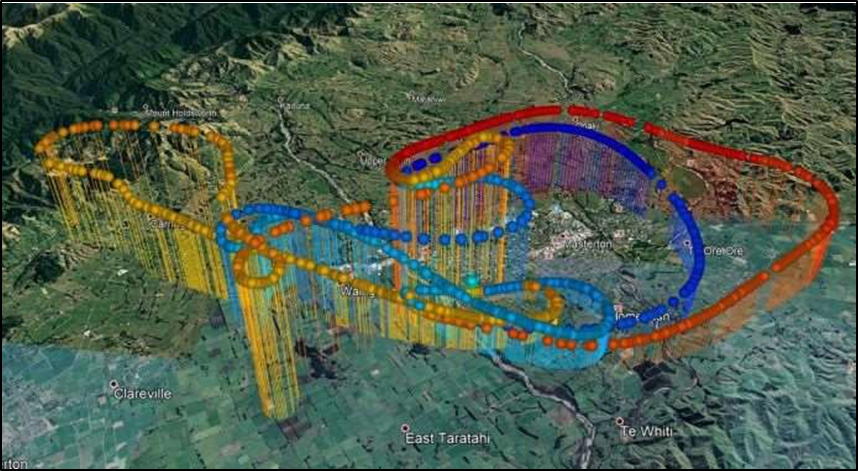

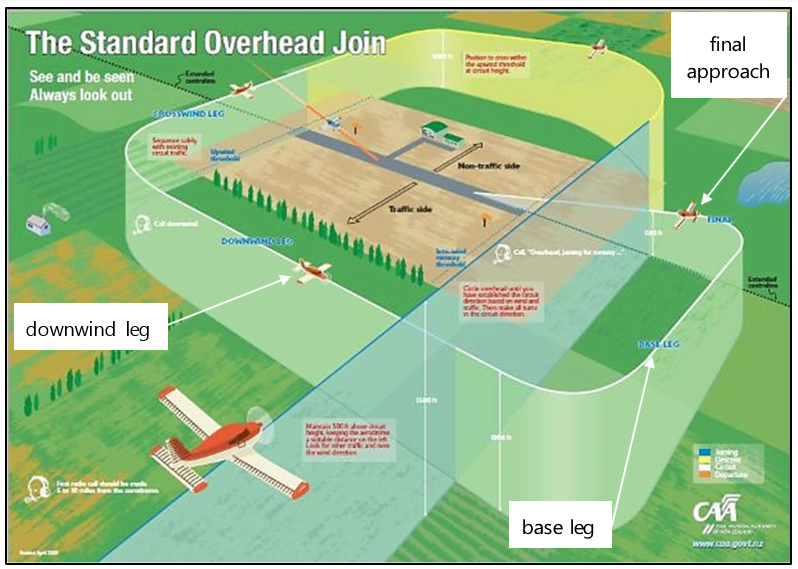

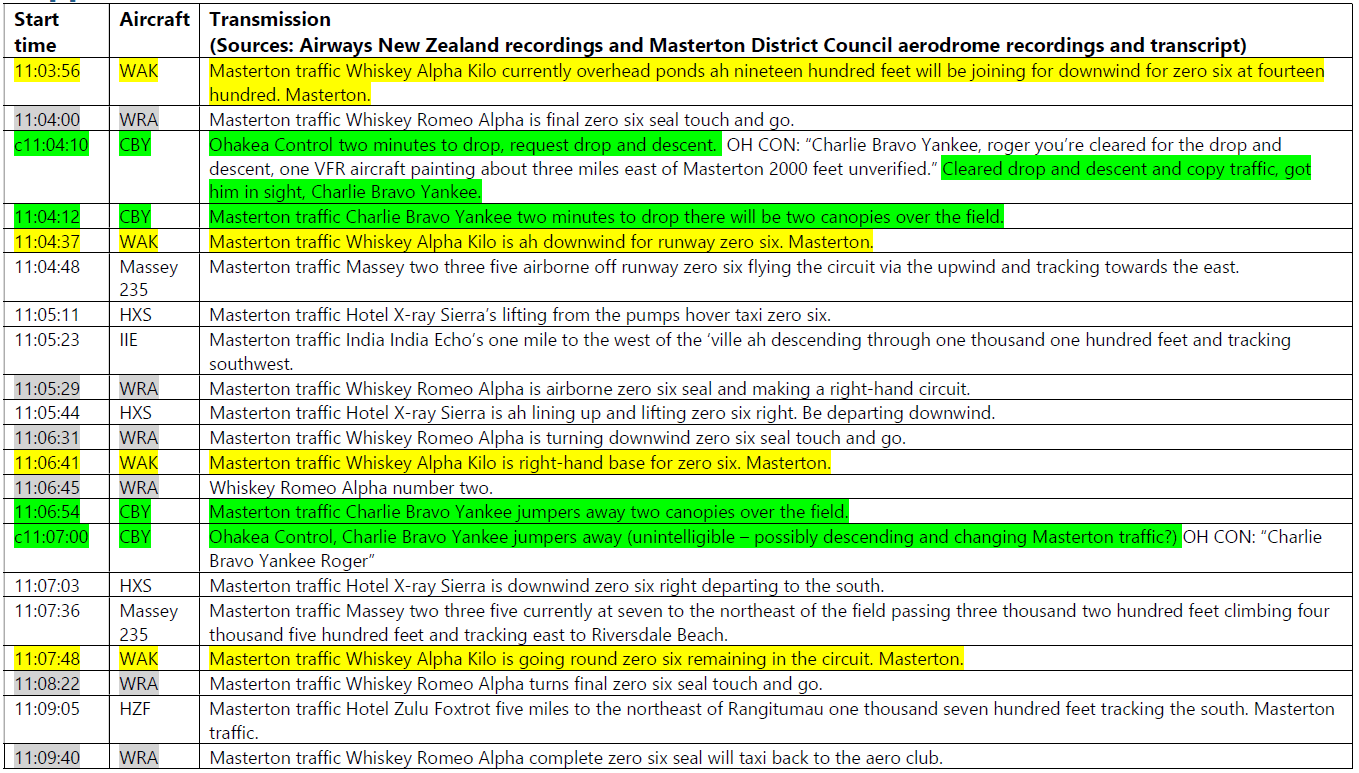

- At 1052:49, the pilot of ZK-WAK called taking off from runway 06 to vacate to the north of the aerodrome, returning to Masterton about 10 minutes later (see figure 4). The second Tecnam, ZK-WRA, was operating in the runway 06 circuit at this time. Between about 1100 and 1104, the pilot of ZK-CBY used the aeroplane’s second radio to call Ohakea Control and obtain air traffic control clearance to enter the controlled airspace and climb to 13,000 feet (4000 metres) over the aerodrome for the drop. At 1104:12, the pilot of ZK-CBY made a call on the local radio frequency advising ”two minutes to drop, there will be two canopies over the field”.

- At 1104:37, the pilot of ZK-WAK called downwind for runway 06. Two minutes later the pilot called right base for 06. At 1106:54, the pilot of ZK-CBY made a radio call reporting “jumpers away, two canopies over the field”. The aeroplane then descended with the pilot only on board. At 1107:48, the pilot of ZK-WAK called ”going around 06, remaining in the circuit”.

- At 1109:40, the pilot of ZK-WRA called that it had landed and was taxiing back to the aero club. This was immediately followed by a call from ZK-WAK, ”Masterton traffic, Whisky Alpha Kilo is downwind for runway 06 Masterton”. A minute later at 1110:42, the pilot of ZK-CBY called ”Masterton traffic, Charlie Bravo Yankee, Ponds 3000 feet tracking to join right base 06 left”. At 1111:53, the pilot of a locally based helicopter radioed ”joining base 06 right number two behind Charlie Bravo Yankee”. The pilot of the helicopter had landed south of the Ponds to uplift a student and was following behind ZK-CBY. The helicopter pilot later reported seeing ZK-CBY, but not ZK-WAK, until the two aeroplanes were very close to each other.

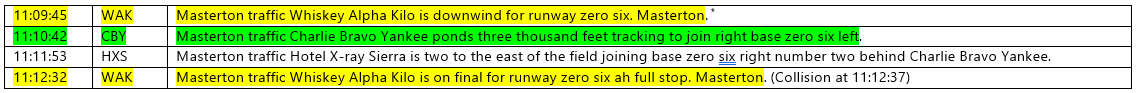

- At 1112:32, the pilot of ZK-WAK radioed advising ”Masterton traffic, Whisky Alpha Kilo is on final for runway 06, full stop Masterton”. ZK-WAK and ZK-CBY collided immediately on completion of this transmission.

- The pilot of the helicopter reported not hearing the landing call from ZK-WAK, but did see the two aeroplanes collide and spiral to the ground. ZK-CBY caught fire as it impacted the ground. The pilot of the helicopter landed nearby and, along with several witnesses, attempted to assist the occupants. The two pilots suffered fatal injuries (see figure 5).

Personnel information

Pilot of ZK-CBY

- The pilot of ZK-CBY held a Commercial Pilot Licence (Aeroplane) and a current ‘class 1’ medical certificate valid until 16 January 2020. The pilot was assessed as fit and healthy, with no restrictions on the medical certificate or known medical conditions.

- The pilot started flying training in March 2017, obtaining a Private Pilot Licence (Aeroplane) in July 2017 and Commercial Pilot Licence (Aeroplane) in July 2018. In late 2018, the pilot visited the operator seeking a job. It was agreed that the pilot needed to gain experience flying tail-wheeled aeroplanes (most aeroplanes, including all the types the pilot had flown to date, were equipped with a main landing gear and nose wheel. Tail-wheeled aeroplanes have distinctly different ground-handling characteristics) before commencing training as a parachute drop pilot.

- The pilot’s logbook recorded that they had returned to Masterton in April 2019 having flown nearly eight hours in a PA18 Piper Cub. The operator’s senior pilot continued the tail-wheel training, flying a further seven hours with the pilot in a DHC1 Chipmunk, all at Masterton.

- On 24 April 2019, the pilot started training on ZK-CBY. The pilot’s logbook recorded him being issued a type rating on the C185 type of aeroplane on 10 May 2019. On 11 May 2019, the pilot obtained a rating for ‘Parachute Drop Operations’ in accordance with the requirements of CAR Part 149 – Aviation Recreation Organisations – Certification (the certificate permitted the pilot to undertake non-commercial parachute drop operations). Between instructional flights, the pilot had also flown as an observer with the instructor on parachuting drop flights.

- On 17 May 2019, the pilot completed a competency assessment with a flight examiner for the issue of a parachute drop certificate in accordance with the requirements of CAR Part 115 – Adventure Aviation – Certification and Operations (the certificate permitted the pilot to undertake commercial parachuting drop operations). The pilot had accrued a total of 272 hours flying at this time, including 108.6 hours as pilot-in-command. The pilot commenced commercial parachute drop operations the next day.

- The pilot last flew on 9 June 2019. At the time of the accident, the pilot had accrued a total of 288 hours, including 24 hours on the C185 type of aeroplane. The pilot had flown 14.6 hours as pilot-in-command on parachute drop operations, completing 30 parachute drops flights.

- A review of the pilot’s 24 and 72-hour history identified no fatigue issues. The pilot’s flatmates and fellow workers reported him to be in good health and his usual self on the day of the accident.

- The toxicology results were negative for any performance impairing substances.

Pilot of ZK-WAK

- The pilot of ZK-WAK held a valid Microlight Pilot Certificate and a current medical certificate. A review of the pilot’s medical assessments and general practitioner notes identified nothing of relevance to the occurrence.

- The pilot commenced flying training in October 2016, obtaining an ‘intermediate’ flight certificate in July 2017, an ‘advanced local’ flight certificate in February 2018 and an ‘advanced national’ flight certificate on 8 February 2019 (the various certificates are about pilot privileges. Under an ‘advanced national’ certificate the pilot was permitted to carry passengers and fly beyond the confines of the local area). The next flight test for the renewal of the certificate was due on 8 February 2020.

- The pilot’s previous flight was on 5 May 2019. At the time of the occurrence the pilot had accrued a total of 99 hours, all on the Tecnam P2002 type of aeroplane and all flown locally.

- A review of the pilot’s 24 and 72-hour history identified no fatigue issues. The pilot was reported to be to be fit and healthy. The purpose of the flight was a short local scenic trip.

- The toxicology results were negative for any performance impairing substances.

Aircraft information

ZK-CBY

- ZK-CBY was a Cessna 185A Skywagon aeroplane, serial number 0420, manufactured in 1962. The aeroplane was powered by a Continental IO-520-D132 engine, serial number 293393R, driving a three-bladed propeller. The C185 was a high-wing aeroplane with fixed landing gear. In its original passenger configuration, the C185 was capable of carrying six occupants.

- The operator purchased ZK-CBY in 2001 and made several modifications in preparation for parachuting. The modifications included installing a three-bladed propeller to reduce noise, adding wing extensions and altering the main door to have it hinge upward and therefore provide a clear path for parachutists to exit. A foot rail was also installed to allow parachutists to gather at the door and exit as a group.

- ZK-CBY had been issued with a standard category Certificate of Airworthiness, which was non-terminating provided the aeroplane was maintained and operated in accordance with the relevant operating limitations and manuals. A review of the documents for the aeroplane show that it was maintained in accordance with the operator’s maintenance programme approved by the CAA.

- The last recorded inspection was a 50-hour inspection completed on 15 March 2019. The last annual review of airworthiness was completed on 19 December 2018. At the time of the accident on 16 June 2019 the aeroplane had flown a total of 17,531 hours.

- The engine had been installed new in the aeroplane on 15 October 1996 and had completed 3,137 hours since new and 1,307 hours since its last overhaul. The engine was fitted with a monitoring system that permitted a pilot to observe cylinder temperatures. There were no known or reported technical issues with either the aeroplane or the engine.

- ZK-CBY was fitted with dual radios that permitted the pilot to listen on two radio frequencies at the same time, but only talk on one. In early 2019, the operator installed an Airborne Collision Avoidance System (ACAS), specifically a FLARM (Flight Alarm). The ACAS was designed to provide an alert to the pilot about other aircraft in the proximity. However, to be effective as an ACAS, the opposing aircraft needed to be similarly equipped. ZK-WAK was not fitted with an ACAS, nor was it required to be. The FLARM also included a tracking facility that recorded the flightpath of ZK-CBY.

ZK-WAK

- ZK-WAK was a Costruzioni Aeronautiche Tecnam P2002-JF aeroplane, serial number 010, constructed in 2004. The Tecnam P2002 is a two-seater, low-wing light aeroplane, popular for initial flight training. The aeroplane was powered by a Bombardier ROTAX 912 S2 engine, serial number 4.923.103, driving a two-bladed Bolly Aviation propeller. The aeroplane was fitted with navigation lights, a strobe light and a landing light.

- ZK-WAK had been issued a flight permit in accordance with CAR Part 103 – Microlight Aircraft – Operating Rules. The Tecnam P2002, with a certified maximum take-off weight of 450 kilograms, was classified as a ‘microlight’ aeroplane. CARs required the aeroplane to be maintained in accordance with the manufacturer’s maintenance schedule and maintenance manual and that ‘annual condition inspections’ be performed. A review of the records for the aeroplane identified some omissions and errors, which mainly related to differences between the newly installed electronic flight time recorder and the manual recording system that continued to be used. Nevertheless, the maintenance documents confirmed the aeroplane was being maintained as directed.

- The last scheduled inspection of ZK-WAK was a flight permit, also known as an annual condition inspection, performed on 7 February 2019. At the time of the accident, the aeroplane had flown approximately 1680 hours and had about 20 hours to run to the next scheduled 100-hour inspection. The technical log for the aeroplane recorded no outstanding or relevant technical issues for the aeroplane.

Communications and recorded data

- Radio transmissions made on the Masterton Aerodrome local area frequency of 119.1 MHz were recorded by the aerodrome operator and made available to the investigation. The transmissions recorded were of good quality and included those made by the pilots of ZK-CBY and ZK-WAK as they flew about the local area and re-joined to land. Recordings of the radio transmissions made by the pilot of ZK-CBY on the Ohakea Control frequency of 125.1 MHz during the time the aeroplane was operating within controlled airspace were also obtained by the Commission. See Appendix 1 for a full transcription of the radio transmissions.

- The FLARM tracking data from ZK-CBY for the approximately 30 previous flights were obtained as part of the investigation. The data provided an accurate record of the flightpaths of ZK-CBY from power-up to shut down, including all of the accident flight information (see figure 6).

- Airways New Zealand radar facilities recorded much of the flightpaths of the two aeroplanes as they flew about the local area, but the coverage did not extend to lower levels. The recordings for ZK-WAK showed the aeroplane flying the downwind leg, but ceased at about the time the aeroplane turned and started descending around the base leg. The radar recordings for ZK-CBY closely matched the FLARM tracking data previously referred to.

Aerodrome information

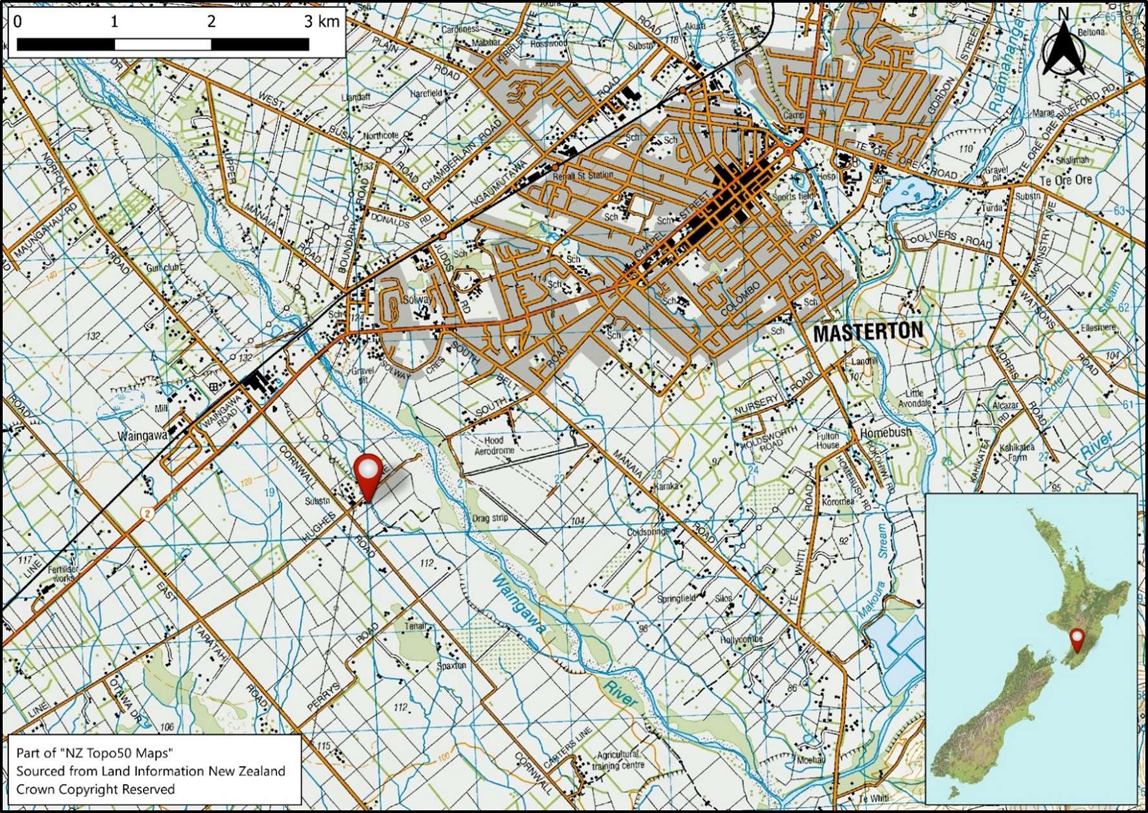

- Masterton Aerodrome, known locally as Hood Aerodrome, was a non-certificated aerodrome (an aerodrome is required to be certificated when it is used for regular international flights or regular air transport involving aeroplanes with a seating capacity of greater than 30 passengers) located on the southern boundary of Masterton township. The aerodrome was owned and operated by the Masterton District Council (MDC), who appointed an aerodrome manager. The manager’s primary function was to manage operations on the aerodrome, including running aerodrome facilities and liaising with aerodrome users and others.

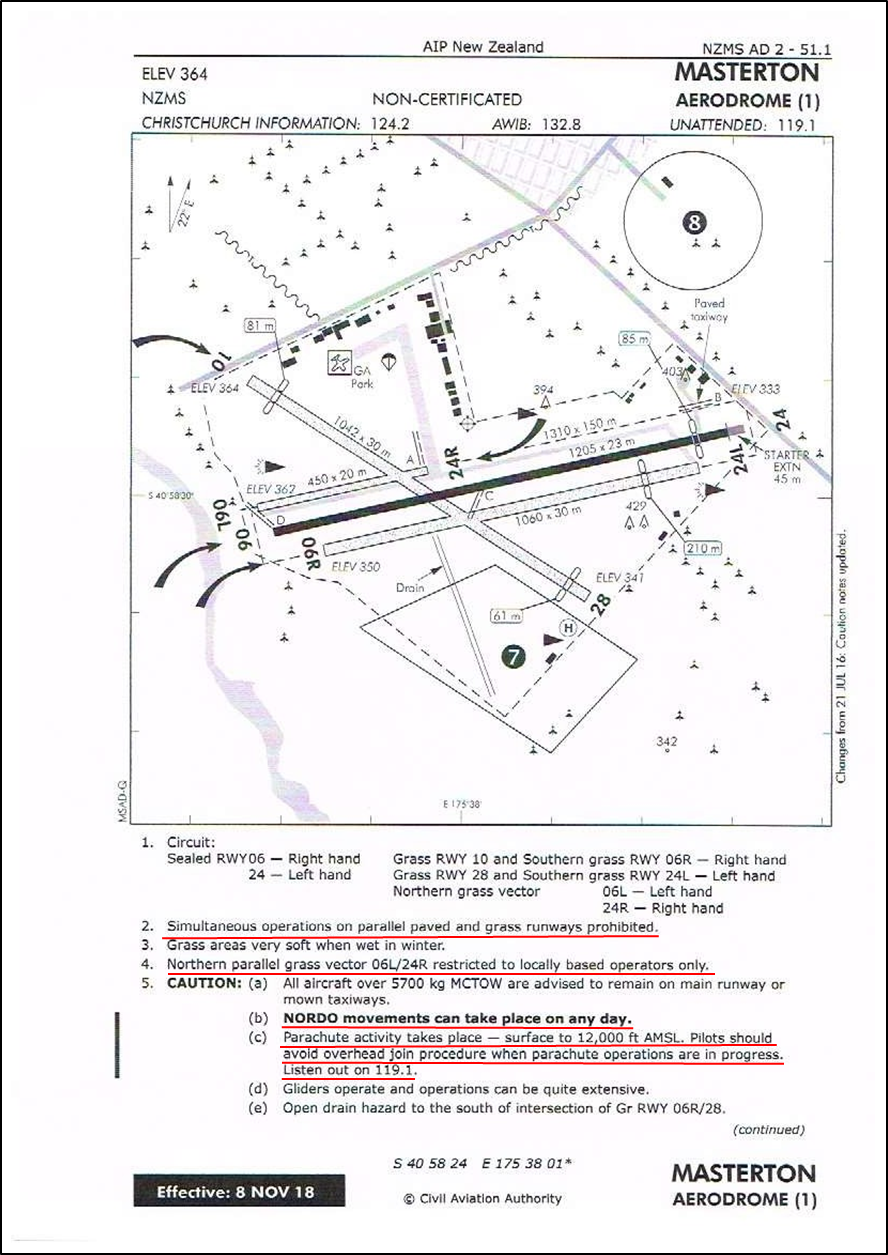

- The aerodrome chart for Masterton recorded the aerodrome as 364 feet (110 metres) above mean sea level. The aerodrome consisted of one bitumen and two grass runways aligned 06 or 24, depending on the take-off and landing direction. A fourth cross-grass runway, runway 10/28, was also available for use (see figure 7). On the day of the accident, the 06 runways were the primary runways in use.

- The standard circuit pattern in New Zealand is left hand unless the aerodrome chart directs a right-hand circuit be flown. The downwind leg of a circuit is to be flown at a height of 1000 feet above the aerodrome elevation unless the aerodrome chart directs otherwise.

- At Masterton half the circuits were right-handed, which was to keep traffic away from the township and minimise any adverse effects, such as noise. The downwind leg was typically flown at 1400 feet above mean sea level to conform to the 1000 feet above the aerodrome.

- The three parallel runways aligned 060° magnetic were identified as either 06L (for 06 left), 06 (for the centre bitumen runway) and 06R (for 06 right). Runway 06L was a left-hand circuit, while 06 and 06R were right-hand circuits. The three runways were located about 75 metres apart when measured from the centrelines of each runway.

- Runway 06L was originally located further to the north within a large grassed area. It was established to provide a designated runway for local operators, including helicopters and the many vintage aircraft based at the aerodrome. The performance capabilities of these aircraft meant that they were able to remain clear of the township and close to the aerodrome when flying circuits. In about 2003, building development near the eastern end of the runway required the runway to be repositioned closer to the main 06 bitumen runway.

-

The Masterton Aerodrome chart published by the CAA and current at the time of the accident contained numerous notes for pilots when operating at the aerodrome. Notes relevant to this occurrence included:

1. Simultaneous operations on parallel paved and grass runways prohibited.

2. Northern parallel grass vector 06L/24R restricted to locally based operators only.

3. NORDO (non-radio equipped aircraft) movements can take place on any day.

4. Pilots should avoid the overhead join procedure when parachute operations are in progress (this was emphasised in another note, recommending the standard overhead join be flown except when there was parachuting taking place).

5. Agricultural aircraft operate from the aerodrome, departing and approaching at low level (see figure 8).

- The aerodrome was located within uncontrolled ‘class G’ airspace with no air traffic control service present. See paragraphs 2.59 to 2.67 about CARs and procedures

- The aerodrome was equipped with an Aerodrome and Weather Information Broadcast (AWIB) facility. Local weather information, including wind direction and strength, could be obtained by transmitting four quick pulses on 132.8 MHz.

- An aerodrome user group had been established to help coordinate activities on the aerodrome and met semi-regularly. Minutes of the group’s meetings for the preceding two years were reviewed as part of the investigation.

- The position of chair of the group’s committee was held by the owner of Skydive Wellington. The group had established an aerodrome safety officer position to assist in addressing any safety-related matters. This position was initially filled by a retired commercial pilot with extensive local experience. At the time of the 16 June 2019 accident the MDC had appointed two safety officers on a casual basis. The aerodrome manager attended committee meetings in a coordination role, but to avoid any potential conflict of interest was never in the position of committee chair.

- The aerodrome manager at the time of the accident was employed by the MDC in February 2016 on a part-time basis, a position previously held by an independent contractor. The council provided a job or position description for the role of the manager, which was primarily to promote aviation and activities on the aerodrome in line with the council’s vision. The manager advised there was no formal qualification or training for the role. The manager had relied on a handover from the previous contractor, attending conferences and training opportunities, networking and their aviation background to do the job (the aerodrome manager held a private pilot licence qualification).

- In 2018, the aerodrome manager established an aerodrome safety committee. The purpose of the committee was to discuss hazards and issues on the aerodrome and determine ways of making improvements. The committee had met on three occasions before the accident on 16 June 2019.

- The aerodrome manager and the safety committee were also collating a documented risk management framework, known as a safety management system (SMS), for aircraft operations (a system for hazard identification and risk management, safety targets and reporting processes, procedures for audit, investigations, remedial actions and safety education). Masterton Aerodrome, as a non-certificated aerodrome, was not required to have an approved SMS and the MDC reported there was some opposition to adopting one. However, it was agreed by the aerodrome manager and major users that an SMS would provide a useful safety tool. Any work on the aerodrome was undertaken in accordance with MDC’s health and safety policy.

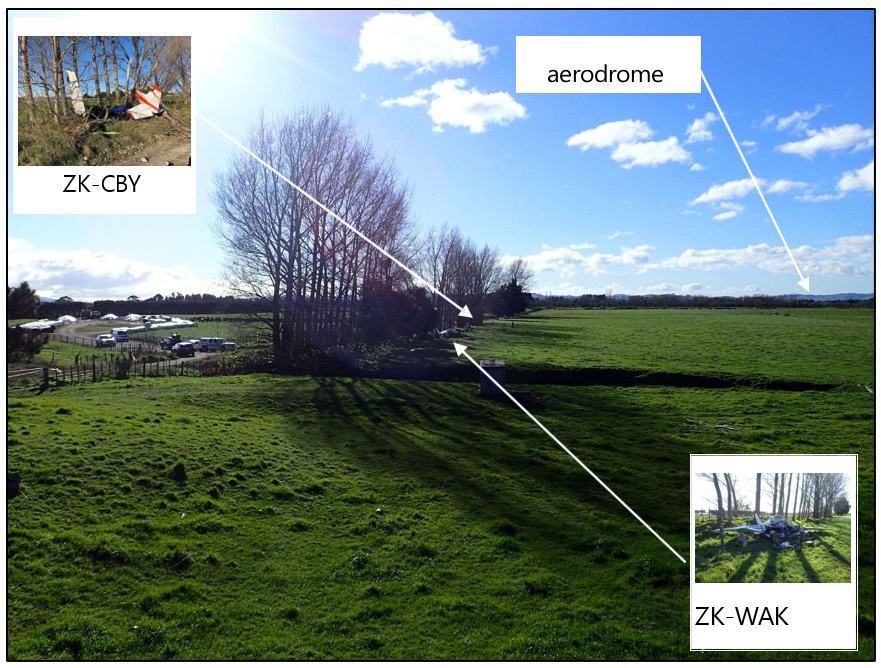

Site and wreckage information

- The two aeroplanes collided over sparsely populated farmland, approximately 300 feet (90 metres) above the ground. The collision occurred in line with runway 06, approximately 1.2 kilometres short of the runway threshold. Pieces of debris from both aeroplanes, including propeller fragments, Perspex and other light items, were spread over an area of about 200 square metres. The main structures of the two aeroplanes had fallen nearly vertically to the ground, approximately 55 metres apart and along a row of trees adjacent to a shingle road.

- ZK-CBY descended through the trees nose first, catching fire as it struck the trees and ground. The pilot of the helicopter following ZK-CBY had landed nearby, and using the helicopter’s fire extinguisher attempted to extinguish the fire, but was unsuccessful. The fire destroyed much of the aeroplane, with the exception of the outer sections of the wings and tailplane.

- ZK-WAK struck the ground nose first, causing the fuselage to split open forward of the wings. After striking the ground the aeroplane rocked back onto its main wheels and tail. There was no fire.

- The two aeroplanes were examined on-site before the remaining fuel in ZK-WAK was drained. The two aeroplanes were then dismantled, where necessary, and removed for further examination.

- The degree of damage sustained by both aeroplanes meant that it was not possible to determine the configurations of the two aeroplanes at the time of impact, including the position of the landing flaps and aeroplane lighting.

- Examination of ZK-WAK identified rubber transfer marks on the right side of the cabin area, about in line with the aeroplane’s seating. Paint transfer was also evident on the right upper wing surface, between 1 and 2 metres in from the wingtip. There were gouging or dents coincidental with the paint transfer marks. The transfer marks were of a pale red or orange colour. This colour matched the colour painted on ZK-CBY. The damage on the upper surface of the right wing of ZK-WAK was also consistent with the damage sustained by the right wingtip of ZK-CBY (see figure 9).

Organisational information

Skydive Wellington

- ZK-CBY was owned and operated by Sky Sports (NZ) Limited, trading under the name of Skydive Wellington (the operator). The operator was established in about 1992 and was certificated under CAR Part 115 – Adventure Aviation – Certification and Operations. The operator started parachuting flights at Masterton Aerodrome in 2001 and undertook both commercial and sports jumping. This included tandem jumping, involving a tandem master and rider, and solo parachutists. ZK-CBY was the operator’s only aircraft.

- The operator’s chief executive, who was also the sole director and shareholder, was an experienced parachutist and parachute instructor with over 6,000 jumps since 1970. The chief executive held no pilot qualifications, and so piloting-related matters were usually delegated to the operator’s regular pilot (the instructor) who held an instructor qualification.

- The instructor undertook aeroplane type training for the operator and parachute drop ratings for the Part 149 approved New Zealand Parachute Industry Association. For the jump training of the pilot of ZK-CBY, the pilot accompanied the instructor as observer on about 15 parachuting flights before they started flying with parachutists (during parachuting operations, the second pilot’s seat had to be removed to provide a clear path for parachutists to exit the aeroplane).

- At the time of the accident, the operator was working towards implementing an SMS, to update and replace their current organisational management and quality assurance systems. However, this was still in draft form and had yet to be submitted to the CAA for approval in the agreed timeframe, which was 1 February 2021 (some 19 months after the accident).

Wairarapa and Ruahine Aero Club

- ZK-WAK was owned and operated by the Wairarapa and Ruahine Aero Club, more commonly known as the Wairarapa Aero Club. The club owned two Tecnam P2002 aeroplanes, ZK-WAK and ZK-WRA. The club operated under a CAR Part – 149 Aviation Recreation Organisation, where club members could hire an aeroplane for a private flight.

- The club ran an online booking system, where members could pre-book an aeroplane. Depending on the member’s experience and qualifications, a booking may have needed the approval of one of the club’s instructors. The pilot of ZK-WAK had pre-booked the aeroplane online in accordance with the club’s procedures and was permitted to undertake the flight.

Civil Aviation rules and procedures

Rules

- Rules on ‘right-of-way’ and ‘operating on and in the vicinity of an aerodrome’ were contained in CAR Part 91 – General Operating and Flight Rules (part 91 was amended on 10 May 2019, but none of the changes affected the CARs referred to in this section of the report).

- CAR 91.127 – Use of aerodromes – detailed the conditions on the use of an aerodrome and included the requirement to comply with notified limitations and operational conditions.

- CAR 91.223 – Operating on and in the vicinity of an aerodrome – directed pilots to observe other aerodrome traffic for the purpose of avoiding a collision and to conform with or avoid the traffic circuit formed by other aircraft. A pilot was to perform a left-hand circuit when approaching to land unless the published landing chart directed a right-hand circuit.

- CAR 91.227 – Operating near other aircraft – directed that no pilot was to operate an aircraft so close to another aircraft as to create a collision hazard.

- CAR 91.229 – Right-of-way rule – directed all pilots, when weather conditions permitted, to maintain a visual lookout so as to ‘see and avoid’ other aircraft. The pilot of an aircraft that is obliged to give way to another aircraft must avoid passing over, under, or in front of the other aircraft unless well clear.

- CAR 91.229 – described various situations where a collision might occur, including overtaking and landing. The pilot of an aircraft overtaking another aircraft must avoid that aircraft. An aircraft on final approach had priority.

- See Appendix 2 for the full text of the relevant CARs.

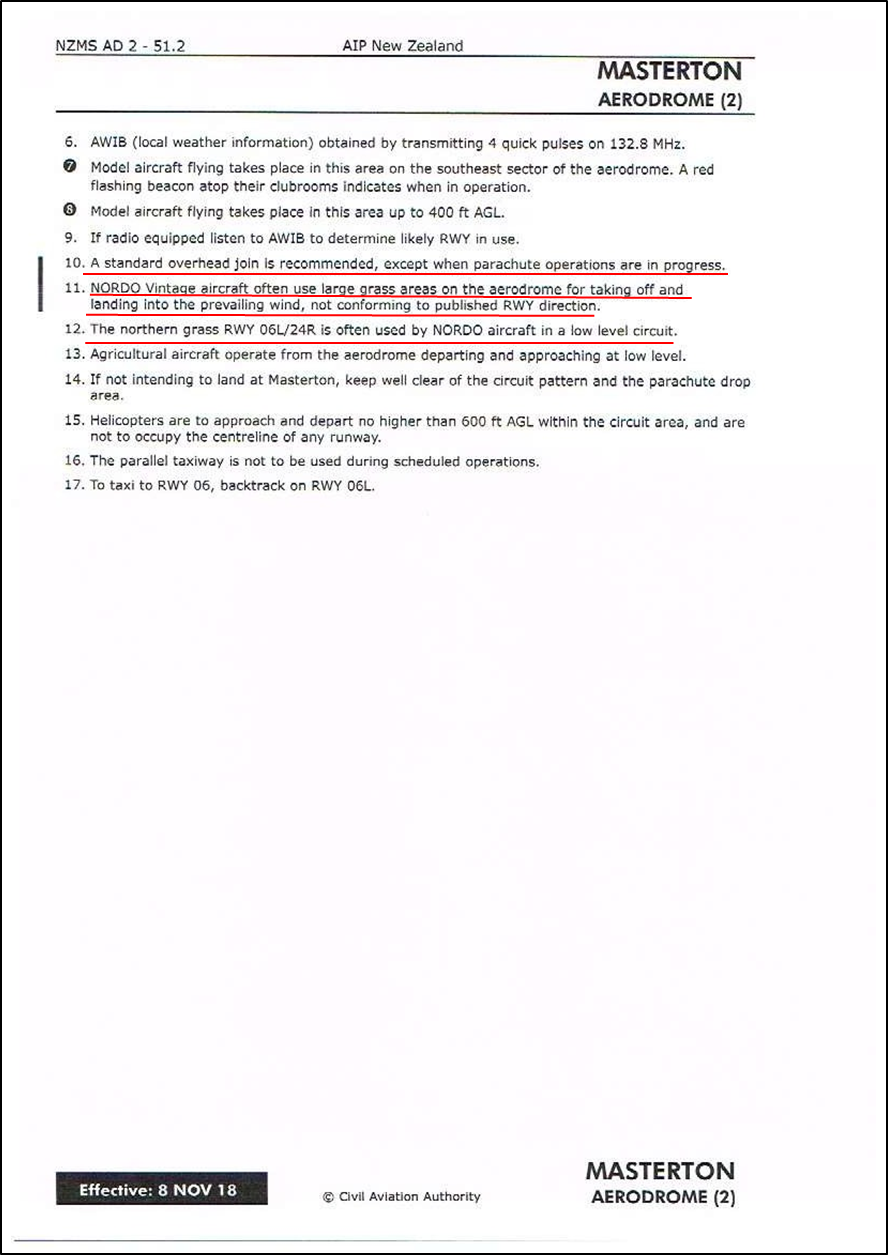

Joining procedures

- The joining procedures to be followed at aerodromes in New Zealand were contained in the Aeronautical Information Publication New Zealand (AIP). Some aerodromes around New Zealand, mainly those with an air traffic service, had specific joining procedures for pilots to follow, but most uncontrolled aerodromes did not (exceptions generally included those uncontrolled aerodromes where parachuting took place, for example Taupo). Unless stated otherwise, a pilot could therefore join an aerodrome via any part of the circuit, including the downwind, base or final approach, provided it complied with CAR 91.223 (see figure 10).

- Where a pilot was unfamiliar with an aerodrome or unsure about the conditions, they could join via a standard overhead join. The CAA Flight Instructor Guide stated that “The standard overhead join procedure is a recommended means of complying with this rule…”, referring to CAR 91.223 (CAA, 2021). The AIP included similar directions.

Mid-air collisions

- The Commission has investigated two other fatal mid-air collisions since 2008. On both occasions the collisions occurred over or near non-certificated aerodromes.

Paraparaumu, 17 February 2008

- On 17 February 2008, a light aeroplane and a small helicopter collided over Paraparaumu Aerodrome. A student pilot in the aeroplane and an instructor and student pilot in the helicopter were all killed (TAIC Report 08-001, Cessna 152 ZK-ETY and Robinson R22 ZK-HGV, mid-air collision, Paraparaumu, 17 February 2008).

- The pilot of the aeroplane was following a standard joining procedure for a sealed runway that took it into the path of the helicopter, which was operating in an opposing circuit direction for a parallel grass runway. The investigation determined that the three pilots had probably been concentrating on flying their aircraft and planned manoeuvres to the detriment of listening and maintaining an effective lookout. The pilots of both aircraft had made appropriate radio calls that should have alerted the other as to their position and intended flightpath, but none of them responded to the other’s call and none appeared to take any avoiding action.

- The Commission made a number of recommendations to the CAA to improve safety, including the need to monitor operations at non-certificated aerodromes, the need for effective visual scanning and active listening, and to review operations at other aerodromes around New Zealand that have opposing circuits (left and right circuit directions for parallel runways).

Feilding, 26 July 2010

- On 26 July 2010, two light aeroplanes collided near Feilding Aerodrome. An instructor and a student in one of the aeroplanes were killed, while a student pilot in the second aeroplane managed to make an emergency landing onto the side of a runway (TAIC Inquiry 10-008: Cessna 152 ZK-TOD and Cessna 152 ZK-JGB mid-air collision near Feilding, Manawatu, 26 July 2010).

- The instructor and student were practising a joining procedure when their aeroplane collided with the second aeroplane that was in the process of departing to a training area. The investigation determined that the pilots of the two aeroplanes had made the appropriate radio calls announcing their locations and intended flightpaths. However, the pilots appeared not to have comprehended the relevance and importance of the other’s calls and did not take appropriate action in time to avoid the collision.

- The Commission made a number of recommendations to the CAA to improve safety, including educating pilots on the importance and limitations of the principle of ‘see and avoid’ as a final defence against a collision and of radio calls, both transmitting and listening.

- The two reports detailed above made reference to 12 previous mid-air collisions that had occurred in New Zealand in the preceding 20 years and to several overseas studies. See Appendix 3 for relevant extracts from the reports into the two mid-air collisions and recommendations made as a result.

CAA and WorkSafe New Zealand

-

Masterton Aerodrome was a non-certificated aerodrome, which was therefore not subject to the same regulatory and auditing oversight of certificated aerodromes. On 30 October 2020, in response to questions posed by the Commission, the CAA advised by letter that a:

…risk-based approach is an inherent feature of [the] New Zealand’s aviation safety regulatory system. It is also articulated in the CAA’s Regulatory Operating Model; a model that recognises regulatory resources are not unlimited and must be deployed in a risk-based approach in which the nature of the aviation activity conducted and the impact on any third parties of safety failure will inform the type and level of oversight.

- Further, the CAA advised that it was the designated agency ”only for aircraft in operation” (emphasis in original), and “That ‘WorkSafe [New Zealand] is the primary regulator for aerodromes under the HSWA” (Health and Safety at Work Act 2015). They also advised that ”Nothing in the designation serves to detract from the primacy of WorkSafe as the lead regulatory agency for aerodromes as a Person Conducting a Business or Undertaking (PCBU) under their HSWA obligations”.

- While WorkSafe New Zealand was New Zealand’s primary workplace health and safety regulator, CAA had, under Prime Ministerial designation, been designated with limited health and safety functions for the civil aviation system. CAA’s jurisdiction covered:

- work preparing aircraft for imminent flight

- work on board an aircraft for the purpose of imminent flight or while in operation

- aircraft as workplaces while in operation.

- For the purposes of CAA’s health and safety regulatory function, ”in operation” means while the aircraft is taxiing, taking off, flying or landing. CAA had further defined this to mean from the moment of initial movement of the aircraft until the aircraft fully ceases movement, the intent of the pilot being that the operation has ended.

- WorkSafe New Zealand is the workplace health and safety regulator for the aviation sector in all other circumstances. This would include the health and safety practices associated with the operation and management of the aerodrome by MDC.

Analysis Tātaritanga

Introduction

- A pilot is ultimately responsible for ensuring the safety of their aircraft (CAR 91.201 (2), CAR 91.227 and CAR 91.229. 24 In multi-crewed aircraft this is the captain as the pilot-in-command). To help achieve this a pilot needs to build and maintain a mental picture or model of the surrounding world to help identify potential threats and choose the most effective and safest course of action, which has often been termed ‘maintaining situational awareness’. The need to maintain this is especially important in uncontrolled airspace where a pilot does not have the direct support of an air traffic controller. A pilot is therefore solely responsible for ensuring that a safe separation from other aircraft is maintained.

- This accident occurred in a ‘class G’ uncontrolled airspace. Therefore the ‘see and avoid’ principle was both the primary and final defence in preventing a mid-air collision. To assist with this, pilots would follow the rules and approved procedures. They would also make radio broadcasts on the local area frequency, stating their position and intentions. However, not all aircraft are fitted with radios, nor were they required to be.

- In this accident, the pilot of ZK-WAK very likely never saw ZK-CBY approaching from the right and behind, while the pilot of ZK-CBY did not see ZK-WAK in sufficient time to take action and avoid a collision.

- The following section analyses the circumstances surrounding the accident to identify those factors which increased the likelihood of the mid-air collision occurring. The analysis also examines the occurrence regarding previous mid-air collisions that displayed significant similarities, and any safety issues which have the potential to adversely affect future operations.

- Four safety issues were identified as a result and these are described below.

What happened

- On Sunday 16 June 2019, the pilot of ZK-WAK had just completed a short local scenic flight and returned to Masterton Aerodrome to operate in the right-hand 06 runway circuit. At 1112, the aeroplane was on a final approach to land.

- At the same time, the pilot of ZK-CBY was re-joining to land on the left-hand 06L runway, having previously released some parachutists overhead of the aerodrome. The re-join was in a non-standard right-hand direction, as this was how the pilot of ZK-CBY had been instructed to join during their training (see figure 11).

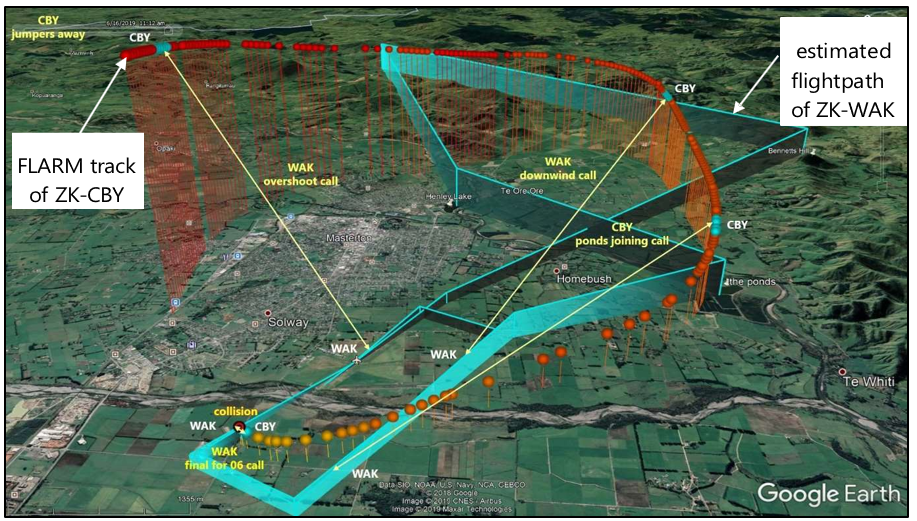

- As ZK-CBY flew around the base leg, ZK-WAK would have been in front of and below ZK-CBY. The pilot’s view of ZK-WAK would therefore have very likely been obscured by ZK-CBY’s engine cowling. As both aeroplanes approached their respective runways, ZK-CBY flying at an approach speed estimated to be at least 50 knots (90 kilometres per hour) faster than that of a Tecnam, rapidly closed-in on ZK-WAK. With ZK-CBY banked to the right as it turned to line up with runway 06L, its right wheel and right wing struck the right side of the cockpit and right wing, respectively, of ZK-WAK (see figure 12). The two aeroplanes collided heavily and initially tangled before separating and spiralling to the ground.

- The two pilots were killed in the collision.

- The investigation found that both pilots were fit and healthy, and fatigue was not a factor. The weather, fine and calm with nearly unlimited visibility, was also not a factor (the effect of the sun is discussed in paragraph 3.15). Both aeroplanes were in an airworthy condition and no mechanical issues were identified. The pilots of both aeroplanes had made appropriate radio calls at various locations along their flightpaths and should have been able to hear the radio transmissions from other aircraft. The failure of a radio receiver in either aeroplane in the few minutes leading up to the collision could not be fully excluded. However, this was considered exceptionally unlikely in the circumstances. The investigation therefore focused on pilot performance and training, operating procedures and oversight.

Civil Aviation rules and procedures

Rules and procedures

- The pilot of an aircraft joining an aerodrome or circuit is required to conform to the established traffic circuit and give way to aircraft that are already operating in that circuit (CAR 91.223 (1) and (2)). On the day of the accident, aircraft at Masterton were using 06 as the designated runway. There were three runways aligned on 06 that could be used. Two runways, 06 and 06R, were designated as right-hand circuits and the third runway, 06L, was a left-hand circuit. Parachuting was also taking place.

- The pilot of ZK-WAK had re-joined the circuit via the right-hand downwind leg for runway 06, the sealed centre runway. This was logical as the pilot had taken off only 10 minutes before and was returning from northeast of the aerodrome. The pilot was therefore familiar with the local conditions and joining almost directly into the downwind leg was the most efficient means of doing so. It also avoided flying a standard overhead joining procedure that may have conflicted with the parachuting taking place.

- The pilot of ZK-CBY returned via a wide descending right turn to join on a right-base leg for runway 06L. This was not in accordance with CARs as runway 06L was a left-hand circuit (CAR 91.223 (3)). To join for 06L and ensure compliance with CARs, the pilot needed to remain clear of the 06 and 06R circuits and join via either a wide left base or a long final straight-in approach, thereby also remaining clear of any parachutists. The possible reasoning for joining via a right base is discussed in paragraph 3.34.

- The pilot of ZK-CBY, as the joining, faster and overtaking aeroplane, needed to give way to ZK-WAK as the slower aeroplane on final approach (CAR 91.229 (d), (e) and (f)). However, this was dependent on the pilot of ZK-CBY being aware of ZK-WAK and observing it in sufficient time to take avoiding action. This is discussed further in the following paragraphs.

See and avoid

Seeing other aircraft

- The CAA Rules direct pilots to observe other aircraft to avoid a collision. Witness observations, weather reports and photographs confirm that the weather conditions at the time of the collision were good and there should have been no environmental impediment to pilots seeing other aircraft in the circuit area.

- At 1112, the sun was determined to be 23° above the horizon and on a bearing of 015° True. As ZK-CBY flew around the base leg, the sun would have been to the front of and above the pilot. The pilot was not wearing sunglasses or a ballcap, but the aeroplane was equipped with a sun visor that if needed the pilot could have used to reduce any downward glare. Further, as the two aeroplanes closed, ZK-WAK was below ZK-CBY and so the sun should not have restricted the pilot of ZK-CBY’s view in this direction. The accuracy with which ZK-CBY was being flown around the base leg and positioned to land on 06L suggests the pilot of ZK-CBY had no difficulty looking in this direction.

- ZK-WAK was mainly painted in white, which should have provided a reasonable contrast against the generally green background. The pilot of ZK-WAK was reportedly trained to have the strobe light on during aeroplane operations. The light was controlled by a rocker switch. The damage sustained meant it was not possible to confirm the position of the switch prior to the collision, but it was considered very likely to have been on. However, a small aircraft on a bright day can still be challenging to locate. Knowing where to look, perhaps directed by a radio call, enables a pilot to focus their attention in a certain area and increase the likelihood of detection.

- The pilot of ZK-WAK had priority to land and was likely unconcerned about ZK-CBY as it was behind ZK-WAK and joining for a different runway. Therefore, as the two aeroplanes closed, the pilot of ZK-WAK would very likely have been looking forward and focusing on preparing to land, not back and to the right. There would have been no expectation that an aeroplane would approach from the rear quarter. Also, the cabin structure of a Tecnam, like most aircraft, would have made it difficult for the pilot of ZK-WAK to see out the rear.

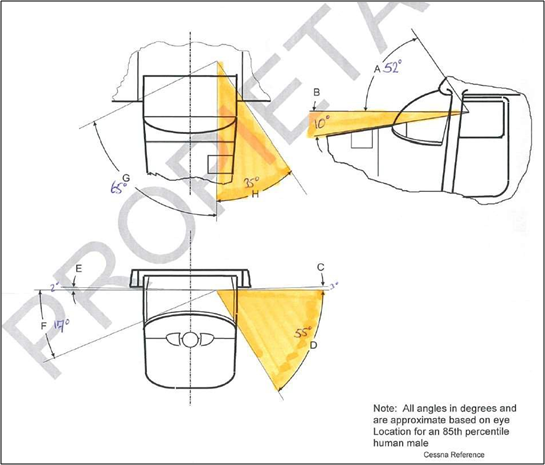

Field of view

- The engine cowling and propeller of a Cessna 185 type of aeroplane extends some 1.6 metres in front of the pilot’s instrument panel. This limits a pilot’s field of view when looking forward. Figure 13 shows the ‘field of view’ chart for the Cessna 185 aeroplane. The chart is based on the ‘85th percentile human male’ (the chart applies to 85% of all males and the pilot would have fitted into this grouping).

- Working back from the known collision point and impact angle, the recorded approach path and speed of ZK-CBY and the likely approach speed of ZK-WAK (based on limited primary radar recordings and flight manual guidance material), it was possible to determine the approximate relative bearings of the two aeroplanes leading up to the collision. From this, it was determined to be very likely that the pilot of ZK-CBY’s view of ZK-WAK would have been obscured by the aeroplane’s engine cowling in the approximately 15–20 seconds leading up to the collision.

- During training, pilots are taught about blind spots and the need to check these areas to ensure they are free of potential hazards. This may be by moving the head and upper body, or by manoeuvring the aircraft. To assist in locating and identifying other aircraft, pilots can also use their radios if fitted.

The need to listen and look

- In the approximately 25-minute period that ZK-CBY and ZK-WAK were airborne, both pilots made the prerequisite radio calls as they flew about the local area and back into the circuit. The recorded radio calls were clear and able to be easily heard and understood. In the five minutes leading up to the collision there were nine radio calls made. Two were from two aircraft transiting through the area. Two were from ZK-WRA, the second Tecnam, reporting ‘finals’ and taxiing in. Two were from a helicopter operating in the vicinity. The final three calls were made by the pilots of ZK-CBY and ZK-WAK. The calls from ZK-CBY and ZK-WAK did not interfere with any of the other calls and suggest that the two pilots were able to hear radio transmissions from other aircraft. See Appendix 1.

- Why the pilot of ZK-WAK called “going round 06 remaining in the circuit” could not be determined. It may have been because it was always their intention, they were not happy with the approach, or simply a realisation that the preceding downwind call did not advise whether it was to be a landing or a touch and go. The subsequent calls were appropriate and gave no indication of any concern by the pilot.

- These radio calls should have alerted the two pilots to each other’s location and intention. If there are any concerns about another aircraft, a pilot is encouraged to challenge or question the pilot of that aircraft (this is communicated in a variety of ways, including CARs, pilot licence flight test guides and CAA Vector magazine articles. Advisory Circular AC91-9, Radiotelephony Manual states: “If there is doubt that a message has been correctly received, a repetition of the message should be requested in full or in part”). For example, by asking them to repeat their position report or confirming they have them in sight. That the calls made by the pilots of ZK-CBY and ZK-WAK did not elicit any response from each other indicates that the pilots either did not consider the other aeroplane to be a threat or they were not actively listening to the content of the calls.

- For the pilot of ZK-WAK, the radio call from ZK-CBY reporting at the Ponds reporting point likely indicated to the pilot that this aeroplane was well behind and (as the joining aircraft) would keep clear of ZK-WAK. The pilot of ZK-WAK may therefore not have considered ZK-CBY to be a threat.

- For the pilot of ZK-CBY, the downwind radio call from ZK-WAK was made as ZK-CBY was still well to the north at about 5000 feet. The pilot of ZK-CBY therefore needed to locate ZK-WAK to ensure a safe separation was maintained as both aeroplanes approached to land on 06 and 06L.

- The downwind call by the pilot of ZK-WAK call was immediately preceded by a separate call from the club’s second Tecnam, ZK-WRA, advising that it had landed and was taxiing back to the club. The sequence and timing of these two calls meant that the pilot of ZK-CBY should not have mistaken ZK-WRA for ZK-WAK. The downwind call from ZK-WAK should have again alerted the pilot of ZK-CBY to be aware there was an aircraft ahead.

- ZK-WRA and ZK-WAK, pronounced over the radio as Whisky Romeo Alpha and Whisky Alpha Kilo, were similar callsigns. However, while confusion on behalf of the pilot of ZK-CBY about the position and intended flightpaths of the two Tecnams cannot be fully discounted, it was considered very unlikely for a number of reasons, including:

- The aero club and parachuting operator were located close to each other on the aerodrome and the pilot of ZK-CBY would very likely have known there were two similarly coloured Tecnams and their callsigns.

- The voices of the two Tecnam pilots sounded different over the radios.

- The radio traffic on the aerodrome frequency (nine radio calls spread over the five minutes leading up to the collision) meant that the frequency was not busy. The nine calls included three from ZK-WAK and two from ZK-WRA.

-

The proximity of the two aeroplanes when the ‘finals’ call from ZK-WAK was made gave the pilot of ZK-CBY no time to locate ZK-WAK (very likely hidden from view) and avoid the collision.

Technologies for collision avoidance

- Advances in technology have resulted in the development of electronic systems that help alert pilots to the presence and threat posed by other aircraft. These include both airborne collision alerting and avoidance systems and ground-based alerting systems such as ‘short-term conflict alert’. ZK-CBY was equipped with a FLARM airborne alerting system. However, these alerting systems usually require both aircraft to be similarly fitted. ZK-WAK was not similarly equipped, nor was it required to be. In uncontrolled airspace, aircraft are not required to be fitted with a traffic alerting device and they may not even have a radio. Therefore, while these technologies would assist in preventing mid-air collisions, the need to ‘see and avoid’ remains critical. The Commission welcomes advances and efforts to implement these technologies as widely as possible.

Aerodrome practices

Safety issue: Non-compliance, unless addressed as soon as practicable, can quickly become accepted and normalised, increasing the risk of an accident.

Safety issue: The lack of a definition of what was meant by ‘simultaneous operations’ had created confusion for pilots.

Non-compliance in the circuit as an accepted practice

- On the accident flight the pilot of ZK-CBY was re-joining via a right base leg for runway 06L when the collision occurred. The pilot had followed the same procedure on the earlier flight that morning. This procedure was not in accordance with CAR 91.223, which stipulated that pilots were to either conform with or avoid the circuit established by other aircraft and perform a left-hand circuit for 06L. The pilot therefore needed to remain clear of the 06 and 06R circuit patterns.

- To land on 06L, the pilot could have re-joined either via a wide left base or straight in. With parachuting taking place it would not have been safe to re-join via either a standard overhead joining procedure or the downwind leg. The notes on the aerodrome landing chart reflected this.

- A review of the FLARM tracking data for ZK-CBY showed that the pilot of ZK-CBY would return via the Ponds reporting point, regardless of the runway in use. The data showed that when the 06 runways were in use, it had become routine practice for the pilot to take-off on 06 (the aeroplane would be heavier and so the longer runway was required) and land on 06L on some six occasions since 8 June (two earlier flights on 18 May, the pilot’s first day of commercial dropping, landed on 06R). All other flights had landed on runway 24.

- The pilot had been taught during training to re-join via the Ponds reporting point and, when 06 was in use, to join right base and land on 06L. This informal practice dated as far back as 2015 or 2016. It was reported to Commission investigators that an experienced and long-time local pilot had recommended to the then parachute drop pilots to re-join via right base for 06L. This procedure offered several advantages, including:

- ‘the Ponds’ was a well-known and obvious location and reporting point that suited the descent profile of the parachuting aeroplane for both runways

- it avoided flying near the township, thereby minimising noise nuisance

- it was easier to land a tail-wheeled aeroplane on grass (a grass surface was better for directional control, especially for low-time pilots still learning to handle the unique characteristics of a tail-wheeled aeroplane).

- landing on grass resulted in less wear on the tyres

- it was closer to the operator’s base and avoided having to cross other active runways after landing

- it avoided two aircraft being ‘belly up’ (having the underside of an aircraft facing the opposing traffic, thus limiting a pilot’s view in this direction) to each other as they turned onto finals, making it more difficult to see the opposing aircraft.

- This non-standard procedure was then adopted by the operator’s pilots and passed onto any new pilots who joined. The operator-owner was aware ZK-CBY was being landed on 06L, but was not a pilot and therefore not aware the procedure was in conflict with CARs. The operator-owner instead relied on the company’s pilots to manage the flying side of the business.

- Interviews of current and former local pilots at Masterton confirmed that the non-standard procedure flown by ZK-CBY, and sometimes other aircraft, had become an accepted routine practice at Masterton. The interviews included many experienced local pilots of long-standing, aerodrome personnel, and current and former CAA staff who flew at Masterton.

- A review of the aerodrome’s user group records going back five years and the safety committee meeting minutes found no reference to the non-standard joining procedure. The CAA’s incident data base also identified no incidents, complaints or reference to the non-standard procedure.

- Safety culture is an expression of how safety is perceived, valued and prioritised at all levels within an organisation (including an aerodrome environment) and reflects the extent to which individuals, and groups are committed to safety (the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Safety Management Manual (Doc 9859), 2018). Fostering an environment where there is a willingness to report and manage risks to safety is an essential component of a healthy safety culture.

- The passive acceptance of the non-compliant behaviour, the absence of proactive safety reporting and the resistance to adopting an aerodrome SMS indicate that the safety culture at Masterton was deficient.

Identification of non-compliant behaviours

- Further to the questioning about circuit behaviours, a sample of flight examiners, chief flying instructors and senior pilots from around the country were contacted to determine if routine non-compliance at aerodromes was a wider issue than just Masterton. Most of those contacted confirmed that non-compliance was not unusual and was almost solely confined to unattended aerodromes – those without an air traffic service in attendance.

- This general non-compliance at unattended aerodromes is understandable. When an incident occurs at an attended aerodrome there would usually be at least three parties present, one being a controller or possibly an aerodrome flight information service person (a person located in a tower providing aerodrome information only, for example weather and runway conditions, but not a controlling service). It was therefore less likely that the incident would be ignored or hidden. Whereas, at a small unattended aerodrome the pilot(s) involved may not wish to officially report an incident for whatever reason. Also, at an unattended aerodrome, if the incident was a near collision one or both of the pilots may never have seen the opposing aircraft and might not be aware of how close they had come.

Incident reporting

-

Following the Paraparaumu and Feilding mid-air collisions, the CAA commissioned a review of joining procedures at uncontrolled aerodromes (review of Joining Procedures at Uncontrolled Aerodromes, Aviation Safety Management Systems Ltd, 2 July 2013). The review found, among other things, that:

…there is significant under-reporting of incidents at uncontrolled aerodromes.

Anecdotally, the level of under-reporting appears to be in the order of only 1-in-5 to 1-in-10 incidents are reported, with the extent of under-reporting varying across aerodromes.

This was evidenced at Paraparaumu Aerodrome where a flight information service was established following the mid-air collision there in February 2008. The incident reporting rates increased significantly, despite the traffic levels remaining about the same

- Should a non-compliant action or procedure go unchallenged or be accepted it risks becoming normalised. This may suit local operators who are aware of the non-compliance and modify their actions to accommodate it. However, it may also increase the risk of an accident, especially for those unfamiliar with the ad hoc procedure. Were a new non-standard action or procedure to be identified that might offer some benefit, then it needs to be considered by the appropriate parties and a risk benefit review undertaken. If accepted, it might then be added to the notes for all users to be informed. An example of this was the note on the Masterton landing chart that overhead joins were to be avoided when parachuting was taking place.

Simultaneous operations

- The two aeroplanes were on final approach to land when they collided 1 kilometre from the threshold or start of the runways. The aerodrome chart included a note stating that ”Simultaneous operations on parallel paved and grass runways prohibited”.

- Interviews of local pilots provided different interpretations of what simultaneous operations meant. Responses ranged from not allowed to be side-by-side with another aircraft to not allowed to cross the threshold of a runway until the other aircraft had cleared the far end of a runway.

-

CAA documents did provide some guidance. However, most of this related to parallel runways at controlled aerodromes and involved aircraft landing under instrument flight rules. There was no guidance material that related to parallel runways at uncontrolled aerodromes, such as Masterton. Early editions of the CAA’s Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP) – Planning Manual did provide a definition which stated:

Simultaneous operations

Two or more aircraft operating from parallel runways, taking off and/or landing at the same time. In this context take-off is from the start of the take-off roll to becoming airborne, and landing is from touchdown to completion of the landing roll.

However, with the digitisation of the AIP in about 1999, this definition was removed.

- Had there been a clear definition that was understood by pilots, and if the pilots of ZK-CBY and ZK-WAK had been aware of each other, the pilot of ZK-CBY may have been more alert to ensuring the required spacing with ZK-WAK was maintained.

Landing charts

- The investigation found that when reviewing the aerodrome charts for a range of aerodromes, many of the charts used different terms and did not accurately reflect the current status of the information referred to. For example, parachuting operations may have ceased or moved location on the aerodrome.

- The CAA advised that a comprehensive review of all aerodrome charts was to be undertaken to ensure they were both consistent and current as far as practicable.

Mid-air collisions

Safety issue: The defence of ‘see and avoid’ is not foolproof against mid-air collisions and, despite repeated efforts to educate pilots about safety around aerodromes, these types of accidents continue to occur.

- The mid-air collision at Masterton on 16 June 2019 was the third such collision at an unattended aerodrome that the Commission has investigated since 2008.

Common factors

- The three mid-air collisions share some common factors, including:

- the collisions occurred at unattended aerodromes

- each collision involved an aircraft that was re-joining

- the weather conditions on each occasion were good, with little or no cloud and near unlimited visibility

- on each occasion the pilots had made the appropriate radio calls, which should have been heard by the pilot(s) of the opposing aircraft

- all the pilots were familiar with the aerodrome and procedures

- one of the pilots involved in each of the collisions held a commercial pilot licence or higher qualification.

- The Commission’s Paraparaumu report made reference to several international studies. These studies identified similar common factors, such as that most of the collisions occurred at small aerodromes in good weather conditions and involved pilots with a wide range of experiences. See Citations on page 48 for the list of references.

- Following the 2008 Paraparaumu mid-air collision, the Commission conducted a review of mid-air collisions in New Zealand. It found that none of the 12 collisions that had occurred over the preceding 20 years had done so in controlled airspace. Five of the collisions had occurred on or near an aerodrome and the 2010 mid-air collision at Feilding was no different.

Joining an aerodrome

- The international studies into mid-air collisions found that they mostly occurred in or near the circuit. This was consistent with New Zealand’s relatively small sampling and was not surprising. Aerodromes are where there is a greater concentration of aircraft, increasing the risk of a mid-air collision. This is even more so at non-certificated and unattended aerodromes where there is no controller present to oversee and ensure the safe, orderly flow of traffic.

- The joining procedure is an area of potentially higher workload for a pilot. A pilot needs to assess the aerodrome and runway conditions, complete aircraft checks, make radio calls, locate other traffic and manoeuvre the aircraft to fit in with the traffic. At unattended aerodromes, this may include non-radio equipped aircraft. A note in the Masterton landing chart made reference to non-radio equipped aircraft using the large grassed area adjacent to runway 06L.

Weather

- The prevailing weather conditions for the three mid-air collisions were good and so there was no obvious impediment to sighting the opposing aircraft as they flew about the aerodromes. However, bright, fine conditions can mean that aircraft navigation lights and anti-collision beacons may be less conspicuous when compared to duller conditions. Pilots therefore need to be equally alert to sighting other traffic in both good and bad weather conditions. For the three New Zealand mid-air collisions there was insufficient evidence to determine the level of influence the good weather conditions may have played.

Radio calls

- The pilots in the three mid-air collisions all made the required radio call leading up to the collisions. The transmitting of a radio call stating aircraft identification, position and intentions helps other pilots maintain a good mental picture or situational awareness of where other aircraft are and what they are doing. It therefore assists with ‘see and avoid’.

- Pilots may, however, think that having made their pre-requisite radio call they have informed other traffic and can therefore relax. When a radio call is made, pilots need to immediately give it their full attention to determine its relevance and respond appropriately. Should a pilot continue to be unsure about another aircraft, either about its position or intentions, they can use the radio to address these issues and manage any potential risk.

Familiarity

- All seven of the pilots involved in the three collisions were familiar with the applicable aerodrome and its procedures. For six of the pilots it was their home base and the aerodrome they did most, if not all, of their flying from. They therefore had a level of familiarity with the local environment and were likely comfortable in it. However, like the effect of weather, there was insufficient evidence to qualify the effect this might have had in each of the three collisions.

Pilot experience

-

Each of the three collisions involved both students or pilots with low experience and pilots holding a commercial pilot licence. Two of the commercial pilots held instructor qualifications. This was in line with the international studies that showed that mid-air collisions were not experience dependent. Even high-time and highly qualified pilots are having mid-air collisions.

Safety at unattended aerodromes

Safety issue: Aerodrome managers, in particular those at unattended aerodromes, lacked the guidance and understanding of their roles and accountabilities regarding the CARs and the Health and Safety at Work regulations, which was necessary to be able to discharge their responsibilities and ensure the safe operation of their aerodrome.

- The Commission’s investigation into this and previous mid-air collisions identified a lack of guidance and support to aerodrome managers on how to safely operate unattended aerodromes. This was initially highlighted in the Commission’s report into the Paraparaumu accident, which had recommended to the Director of Civil Aviation that CAA staff “monitor aerodromes, particularly non-certificated aerodromes, to ensure safety efforts are best directed to promote the coordinated safe management of flying activities”.

-

In response to the recommendation, the Director of Civil Aviation replied that:

As advised in previous correspondence, as Director of Civil Aviation I have limited regulatory powers with respect to non-certificated aerodromes.

Within the resources available to it, the CAA directs its attention to those aerodromes where risk is assessed as being highest –in this case to certificated aerodromes and non-certificated aerodromes engaged in regular passenger transport operations using 19-seat or more aircraft.

The CAA does not have the resources available to it to monitor all aerodromes ‘equally’. However, CAA staff (e.g., aviation safety advisers, etc), actively engage with aerodrome users and others to identify risks and associated mitigations.

Consequently, I accept the recommendation in principle, with the caveat that the CAA’s actions and engagement are driven by:

-

Assessment of risk; and

-

Targeting resources to areas of highest risk.

This is the CAA’s current practice, which will continue.

- Under CARs, the operators of non-certificated aerodromes were only required to establish procedures to ensure the safe movement of aircraft "on parts of an aerodrome where an unsafe condition exists" and monitor and report ”traffic movement data” for the aerodrome. As a result, CAA oversight of aerodromes was often limited to non-regular visits by aviation safety advisors and possibly other staff. Certificated aerodrome operators by comparison were subject to greater regulatory direction and interaction with the CAA, for example regular audits.

-

On 1 October 2020, the Commission wrote to the CAA seeking an update on the CAA’s role regarding non-certificated aerodromes and the application of the HSWA. The CAA replied, in part, that:

…a risk-based approach is an inherent feature of New Zealand’s aviation safety regulatory system. It is also articulated in the CAA’s Regulatory Operating Model; a model that recognises regulatory resources are not unlimited and must be deployed in a risk-based approach in which the nature of aviation activity conducted and the impact on any third parties of safety failure will inform the type and level of oversight.

The priority CAA may assign to its oversight of various elements of the aviation sector is based on relative risk and not driven by rules or legislation, which are enabling tools.

The CAA recognises that continued oversight is required for private and recreational activity in the civil aviation system but assigns less regulatory resources to this area due to the general lower consequences of failure and impact on the safety of third parties.

- The CAA advised that there was no schedule for visiting non-certificated aerodromes. Visits by aviation safety advisors, for example, are generally driven by Aviation Related Concerns (ARCs). The CAA advised that an aviation safety advisor had visited the aerodrome on 12 occasions in the five years leading up to the accident. Four of the visits were for meetings with a specific person or operator and one to attend an airshow. The purpose and content of the remaining visits were not recorded. There was no record of any meeting with the aerodrome manager or attendance at any of the aerodrome user group meetings.

- The CAA’s priority was on higher capacity operations where the risk consequences of an accident were potentially far greater. The risk-based approach was heavily reliant on the CAA receiving information, for example ARCs, that might generate an increased level of engagement. However, because of the under-reporting referred to in paragraphs 3.42 and 3.43, the level of risk for unattended aerodromes may be significantly higher than suggested by the available information.

- Despite the overlap of HSWA responsibilities between the CAA and WorkSafe New Zealand about the ground and air operations in an aerodrome, the two organisations had no coordinated approach in this area. WorkSafe New Zealand advised that its engagement with aerodromes was limited to post-accident investigations only. There was no proactive support of key participants at an aerodrome, in particular for aerodrome managers.

- Most small unattended aerodromes with low traffic volumes are privately owned. Other larger unattended aerodromes with a mix of private and commercial operations like Masterton are mainly owned and operated by local councils. Commission investigators visited several of these aerodromes to determine if some of the issues identified at Masterton were also present elsewhere.

- Most of the aerodrome managers spoken to did not have an aviation background. In some cases, they had been given the role based on their experience managing council green spaces. As one manager said, they knew how to grow and cut grass and aerodromes typically had a lot of grass

- None of the aerodrome managers spoken to had been given any formal training in this role. Instead, they either learnt on the job or sought guidance from other aerodrome managers. The managers were aware they were required to ensure a safe operating area for aircraft and provide the CAA with an annual report of traffic movement data (CAR 139.505). However, the understanding of what this constituted and how it was to be presented varied. This suggests a need for associated training and support to help ensure the safe operation of their aerodromes.

- Most managers spoken to were aware of CAA’s Advisory Circular, AC139-17-Aerodrome User Groups, and said that they did have a ‘user group’ on the aerodrome. However, the frequency of meetings and the effectiveness of the groups varied.

Role of other organisations

- Commission investigators spoke to WorkSafe New Zealand, NZ Airports Association and Local Government New Zealand (LGNZ) representatives. The NZ Airports Association membership consisted of some 80 members, including about 37 aerodrome operators. Of this about 10 were non-certificated and unattended aerodromes. The chief executive advised that much of the effort was directed to larger commercial aerodromes, but they were still concerned about the support and management of the smaller aerodromes. Their reach into this area was, however, limited given the small number of members from this section of the aviation industry.

- LGNZ is the representative organisation for all 78 local government councils in New Zealand (LGNZ website, current at the time of releasing this report). It therefore has the ability, through its membership, to directly connect with the owners and managers of aerodromes like Masterton. LGNZ representatives spoken to confirmed that LGNZ had had no interaction with the CAA about the support of councils and aerodrome managers in the safe operation of aerodromes.

WorkSafe New Zealand

- In the CAA’s letter dated 30 October 2020, referred to in paragraph 2.76, the CAA advised that the CAA’s participation in activities on non-certificated aerodromes was limited and that ”safe aviation practices were actively promoted through visits by CAA aviation safety advisers”. However, the CAA’s interaction with the aerodrome manager, the aerodrome user group and other key players at Masterton was sporadic, a situation that was repeated at other non-certificated aerodromes around the country.

- The CAA also commented that WorkSafe New Zealand was ”the lead safety regulatory agency for aerodromes as a Person Conducting a Business or Undertaking (PCBU) under their HSWA obligations”. The CAA’s engagement was therefore effectively limited to the operation of aircraft. Some of the aerodrome managers spoken to were not aware that under the HSWA they were considered a PCBU.

- An aerodrome by its very nature involves both aerial and ground activities. It would therefore seem logical that both the CAA and WorkSafe New Zealand would engage with the various operators or organisations on an aerodrome to help promote safer activities taking place on and around an aerodrome.

- The Commission could find no evidence of any collaborative approach by the CAA and WorkSafe New Zealand about aerodromes. WorkSafe New Zealand representatives spoken to by the Commission confirmed that the only interaction WorkSafe New Zealand had had with aerodromes was to do with regulatory enforcement action. WorkSafe New Zealand confirmed that there was the potential for a more proactive safety-focused engagement. Logically, this should be done in coordination with the CAA and potentially involve representative organisations like LGNZ. More formalised support for aerodrome managers could also result in improved safety efforts and results.

Pilot qualifications

- On 11 May 2019, the pilot of ZK-CBY was issued a parachute drop rating in accordance with CAR 61.651 (CAR Part 61 Pilot Licences and Ratings). The Rule required the pilot to hold at least a private pilot licence and have accrued at least 200 hours of flight time, including 100 hours as pilot-in-command. The pilot’s logbook showed that the pilot met this requirement, having accrued a total of 270 hours, including 107 hours as pilot-in-command. The rating permitted the pilot to perform non-commercial parachute drops.

- The holder of an adventure aviation operator certificate was required under CAR 115.559 (for commercial parachuting operations in accordance with Part 115 Adventure Aviation, Initial Issue – Certification and Operations) to ensure that its pilot(s), including the pilot of ZK-CBY, met the following requirements:

- hold a current commercial pilot licence,

- hold a current parachute drop rating,

- hold an aircraft type rating for the type of aircraft to be used, and

- acquired at least 150 hours flight time as pilot-in-command of the category of aircraft to be used for parachuting.

- The operator’s Operations Manual also stipulated a minimum of ”at least 200 hours flight time as pilot & at least 150 hours as PIC [pilot-in-command]”.

- The pilot’s logbook showed that on 17 May 2019, when undertaking the competency assessment check flight to be able to conduct commercial parachuting, they had accrued a total of 108.6 hours only as pilot-in-command. At the time of the accident that pilot had accrued a total of 288 flight hours, including 123 hours as pilot-in-command. The pilot of ZK-CBY therefore did not meet the 150-hour ‘pilot-in-command’ requirement.

- The operator, the instructor who did the training and the flight examiner who performed the assessment were all aware of the 150-hour requirement. However, they were unaware that the pilot did not have the required flight hours at the time of the assessment. Both the instructor and examiner contended that the pilot of ZK-CBY, while not meeting the hours requirement, was nevertheless competent to perform the tasks of a parachute drop pilot. The pilot had completed 28 parachuting drop runs before the accident flight.

- The form used for the parachuting competency assessment did not make provision for a pilot’s ‘pilot-in-command’ hours to be recorded, only the total time flown. See Other safety actions, paragraph 5.24, for further comment.

Findings Ngā kitenge

Masterton

- The pilots were both qualified on the aircraft type being flown and the weather conditions were suitable for flying.

- The pilot of ZK-CBY did not meet the flight time requirement for the issue of a commercial parachute drop rating, but this was almost certainly not a contributing cause of the mid-air collision.

- The pilot of ZK-CBY was flying a non-standard and non-compliant join, as this was how the pilot had been instructed to join.

- Local pilots were aware of the non-standard join, which had become accepted practice on the aerodrome.

- The pilot of ZK-CBY, as the joining aircraft, was required under the CARs to give way to ZK-WAK.

- The pilot of ZK-CBY did not see ZK-WAK in time to avoid the collision.

- ZK-CBY struck ZK-WAK on ZK-WAK’s right side as ZK-CBY closed from the right-rear as it turned onto the final approach to land. The two pilots did not survive the collision.

- The circumstances of the accident, an aircraft joining at an uncontrolled aerodrome, were similar to two previous mid-air collisions investigated by the Commission.

General