On 25 March 2025, the Director of Maritime New Zealand replied:

Maritime NZ reject this recommendation

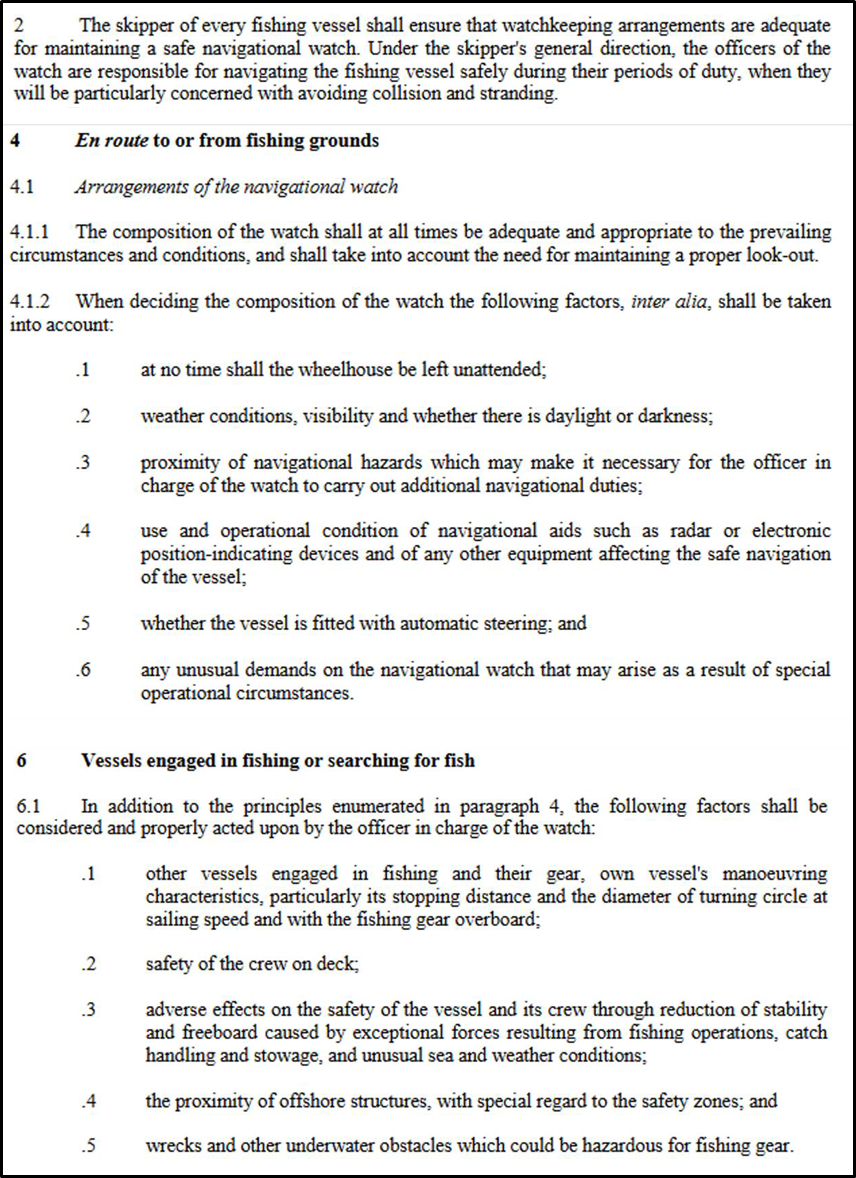

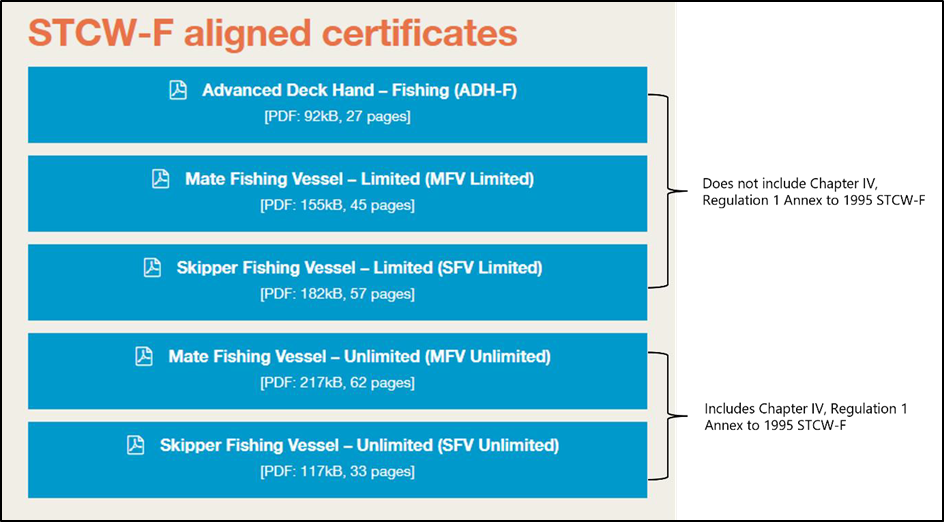

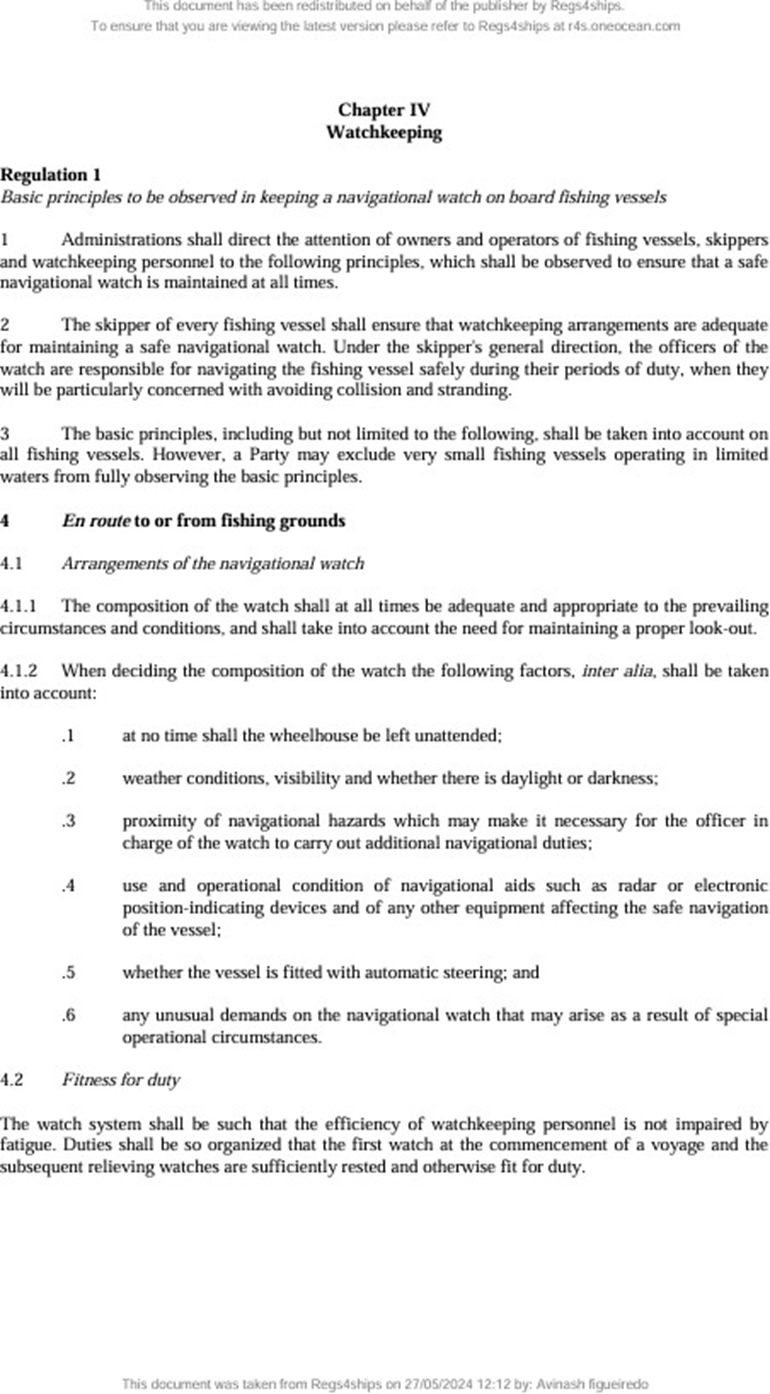

Maritime NZ considers changing the competency framework is unlikely to resolve this issue. The competency frameworks for STCW-F aligned certificates align closely with international requirements. The rules around what is required for watch (including at a competency level) are, in our view, very clear as outlined in our position statement on watch keeping https://www.maritimenz.govt.nz/media/rpkbjmn5/lookout-position-statement.pdf. We do not consider that a review of competency frameworks would have a significant impact on the factors above.

Our strong view, based on ongoing discussions with the sector, are that the drivers of poor lookout and watchkeeping practice are complex; relating to economic constraints (particularly for smaller operators), interactions with other drivers of harm such as fatigue, embedded historical practice, attitudes to government / compliance and a range of other factors. These drivers require an equally multi-faceted harm prevention approach in partnership with the sector and others over time. We would suggest that TAIC considers and encourages work on the wider factors that contribute to poor watchkeeping.

Maritime NZ notes that the STCW framework is being reviewed which will not be complete until around 2030 and the STCW-F framework have just completed a review at the IMO. We are engaging as a priority in this work. If the reviews identify any changes to the conventions or competency requirements we would consider how any changes apply domestically at the appropriate time.

Maritime NZ has had a significant focus on lookout and watchkeeping in the fishing sector for a considerable period of time. As TAIC has noted, this is because good watchkeeping and lookout practice is essential to prevent a range of harms; including collisions, strandings, groundings and safe navigation.

However, ensuring good practice remains a challenge.

Maritime NZ is confident that our current framework, work with the sector, and position statement are closely aligned with STCW-F in regards to watch keeping. As such, Maritime NZ do not support the recommendation.

On 31 March 2025, Pegasus Fishing Limited replied:

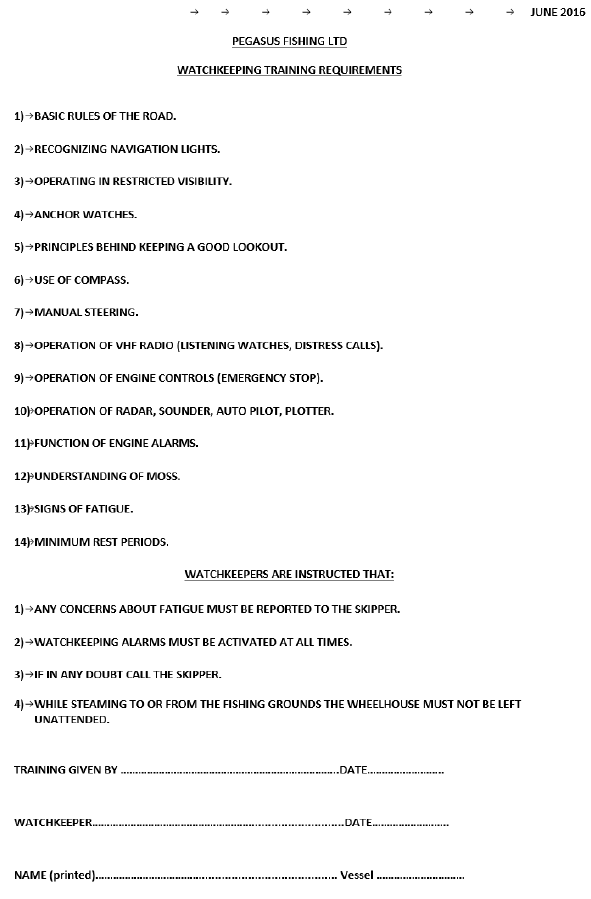

This recommendation can be recorded as accepted and implemented.

Pegasus Fishing took steps immediately after the grounding in September 2023 to review their safety management system which included (but was not limited to) ensuring safe navigational watchkeeping principles were observed during all phases of during the vessel’s operation, including fishing operations.

This included engaging an independent third party to carry out a review of the companies documented procedures and systems, to speak with masters and crew to determine their understanding of policies and procedures, including the respective roles of the master and crew, standing orders, and safety navigational and watchkeeping practices; and to observe the implementation of such practices at sea, by attending and observing fishing trips on each vessel.

Pegasus Fishing also refers to its comments on relevant parts of the draft report as to its safety management system.

Pegasus Fishing ask that paragraph 5.8 of the final report be amended to include a footnote to record that the Commission finalised its report before it had received information from Pegasus Fishing.