At about 4am on 28 July 2021, fishing vessel Commission (motoring) collided with the container vessel Kota Lembah (drifting awaiting port berth at Auckland). Damage to fishing vessel stabiliser and wheelhouse. Neither vessel’s hull was breached. Nobody hurt. TAIC recommendations address 3 key issues: watchkeeping standards & practice; adherence to collision prevention rules; and fatigue.

Executive summary Tuhinga whakarāpopoto

What happened

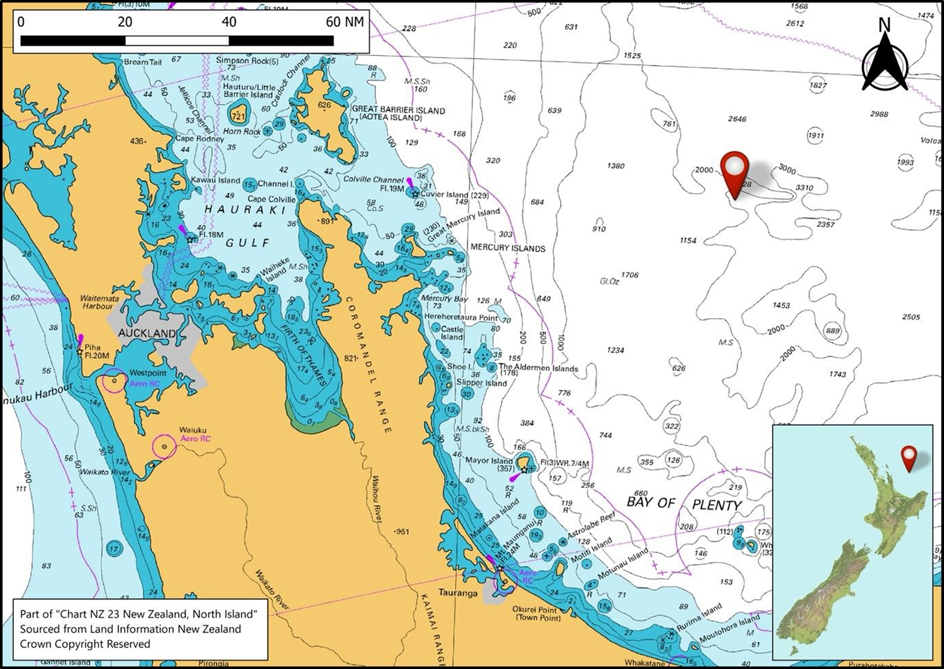

- At about 0400 on 28 July 2021 the longline fishing vessel Commission (F.V. Commission) was motoring at about 6 knots while laying out about 22 nautical miles (NM) of fishing line about 70 NM off the coast in the Bay of Plenty. The F.V. Commission collided with the stationary container vessel Kota Lembah, which had been drifting in the area for several days while waiting for the next available berth at its next port, Auckland.

- The Kota Lembah suffered scraping along its hull near the bow and the F.V. Commission suffered damage to its stabiliser arm and wheelhouse structure. The hull of neither vessel was breached in the collision and nobody was injured.

Why it happened

- The F.V. Commission’s crew had detected the presence of the Kota Lembah on radar but made no attempt to sight the ship or plot it on the radar. There was nobody keeping watch in the wheelhouse at the time of the collision.

- The bridge team on the Kota Lembah had seen and were plotting the F.V. Commission on the radar, and despite the Kota Lembah being required to give way to the F.V. Commission (good industry practice means compliance with minimum regulatory requirements and codes and guidelines published by reputable industry organisations and associations) under the applicable collision prevention rules, it did not do so.

- The watchkeeping standards on both vessels fell well short of good industry practice.

- It was about as likely as not that the F.V. Commission’s skipper was to some degree suffering from the effects of fatigue at the time.

What we can learn

- Adhering to the rules for preventing collisions at sea is the best defence against being involved in a collision. When one vessel deviates from these rules, the risk of collision will be significantly higher. When two vessels deviate from them a collision becomes almost inevitable.

- Fatigue adversely affects human performance and is known to contribute to accidents. Vessels must be resourced so that fatigue can be appropriately managed.

- Non-compliance with standards for achieving navigation safety is also known to contribute to accidents. Anyone involved in keeping a navigational watch needs to be knowledgeable about the collision prevention rules.

Who may benefit

- All seafarers, vessel owners and vessel operators.

Factual information Pārongo pono

Narrative

On board the F.V. Commission

- The F.V. Commission is a 19.5-metre longline fishing vessel. It left Napier on 22 July 2021 with the skipper, two deckhands and an observer (the MPI observer is not considered a crew member and does not become involved in the fishing operation. Their role on board is to monitor the species and quantity caught) from the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) on board. The skipper planned to fish in the area off East Cape and in the Bay of Plenty. The crew made one set of the longline off East Cape and then spent the following three days drifting, waiting for the weather conditions to abate.

- They set the longline again on the night of 26/27 July and then all three crew members slept for about 6 hours while the fishing line ‘soaked’. (left in the water to catch fish) They began hauling the longline at 1430 on 27 July and had retrieved it and stowed the catch by 2200 that evening.

- The F.V. Commission then motored for 4 hours to a new location and began setting the longline for a third time at 0200 on 28 July 2021. The operation involved laying out about 22 NM of line, periodically attaching baited hooks, flotation buoys and Global Positioning System (GPS) locator beacons.

- The operation was undertaken at about 6 knots (one knot equals 1 NM per hour, or 1.852 kilometres per hour) speed. The two deckhands were on the working deck paying the longline over the stern, attaching the hooks, buoys and occasional locator beacon as it went. The skipper was operating the vessel from the wheelhouse. The MPI observer was asleep in a cabin directly forward and below the wheelhouse.

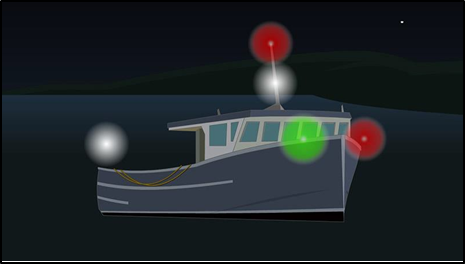

- The F.V. Commission was displaying the usual lights for a fishing vessel when engaged in fishing while ‘underway’.

- The weather was clear skies with a westerly wind blowing at 20 to 25 knots. It was dark but the meteorological visibility was good. There were 2 to 3-metre wind-waves from the west (weather description determined from crew interviews and what was recorded in Kota Lembah’s deck logbook).

- At about 0320 (time calculated from the skipper’s recollection of distance and the corresponding time on the Kota Lembah’s

- voyage data recorder when the F.V. Commission was 4 NM away) the skipper observed a target on the radar, nearly ahead of the F.V. Commission at 4 NM range. The vessel was later identified as the container ship Kota Lembah, which was stopped and drifting. The skipper assumed that because the F.V. Commission was fishing the Kota Lembah would keep clear of them. The skipper did not plot the Kota Lembah on the radar and did not look for it visually. By about 0330 about half of the longline (11 NM) had been deployed, at which point the deckhands attached one of the GPS locator beacons. The F.V. Commission had previously developed a starboard list (a lean to one side caused by an uneven distribution of weights within the vessel) when the previous catch had been stowed. At about 0345 the skipper left the wheelhouse and went to the engine room to correct the list by transferring fuel. While the skipper was in the engine room the F.V. Commission was being steered by autopilot in the wheelhouse. Engine control had been transferred to alternative engine controls on the working deck, where the deckhands could work the engine if required.

- The F.V. Commission was fitted with a retractable stabiliser arm, which was deployed on the port side. The stabiliser arm is a structure that is dragged through the water to help alleviate any rolling motion. At 0401:40 the F.V. Commission crossed the Kota Lembah’s bow with the narrowest of margins; so close that the stabiliser arm collided with the stem of the ship’s bow. The F.V. Commission pivoted around the stabiliser arm and its port bow collided under the flare of the Kota Lembah’s port bow in the vicinity of where the ship’s port anchor was housed (see figure 4). Still on autopilot, and with its engine still driving ahead, the F.V. Commission slowly scraped along the ship’s hull, as it rose and fell with the waves.

- The skipper was knocked down in the engine room, but not injured. The skipper climbed back to the wheelhouse. It was dark and all the skipper could see was the Kota Lembah’s housed anchor out of the port side wheelhouse window. The deck crew were unaware of what had happened. They made their way to the wheelhouse to don lifejackets. The skipper shouted down through the opening to the cabin below to alert the MPI observer, who had slept through the collision.

- The skipper then put the engine in reverse and the F.V. Commission backed away from the Kota Lembah and stopped several hundred metres off the ship’s port bow. The crew made precautionary preparations for abandoning the vessel before making a damage assessment. It soon became apparent that the watertight integrity of the hull was intact. The skipper then attempted to contact the Kota Lembah by Very High Frequency (VHF) radio, but because the various communication antenna on top of the wheelhouse had been damaged this was unsuccessful.

- The crew then severed the fishing line and departed the scene, heading for Tauranga some 70 NM to the west. The F.V. Commission arrived without further incident early the following day, 29 September 2021.

On board the Kota Lembah

- The Kota Lembah departed the port of Lyttelton on 22 July 2021 bound for Auckland. Port congestion in Auckland meant a berth would not be available until 30 July. The ship slow-steamed up the east coast, and rather than proceeding direct to anchor off Auckland the ship stopped on 25 July 2021 and began several days of drifting in the Bay of Plenty, about 70 NM east of Tauranga (this decision was made by the vessel owners due to bunker fuel management).

- At 0000 hours on 28 July 2021, the Kota Lembah was drifting with its main engine on 30 minutes notice should it be required. The ship was displaying the required navigation lights for a ship its size when underway, as well as deck working lights aft and along either side of the main deck.

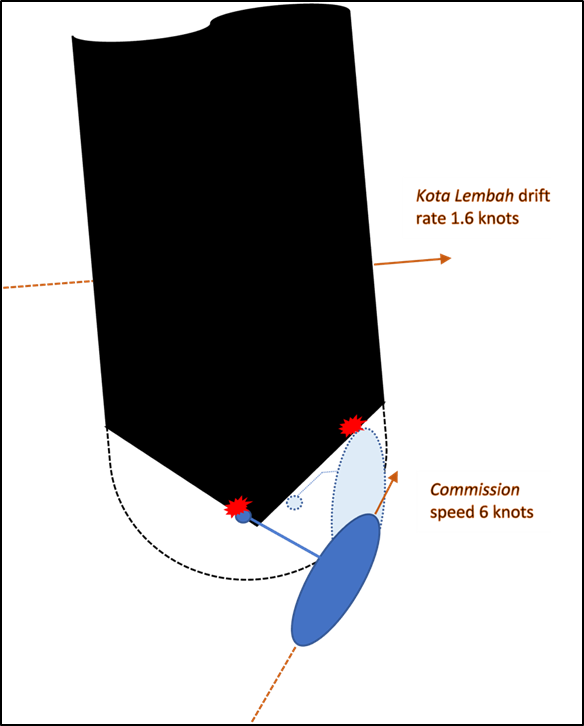

- The second mate was on watch, supported by a watchkeeper Able Body Seaman (AB). The ship was pointing broadly south on a heading of 172 True, but was drifting sideways towards the east under the influence of the westerly wind (refer to figure 5).

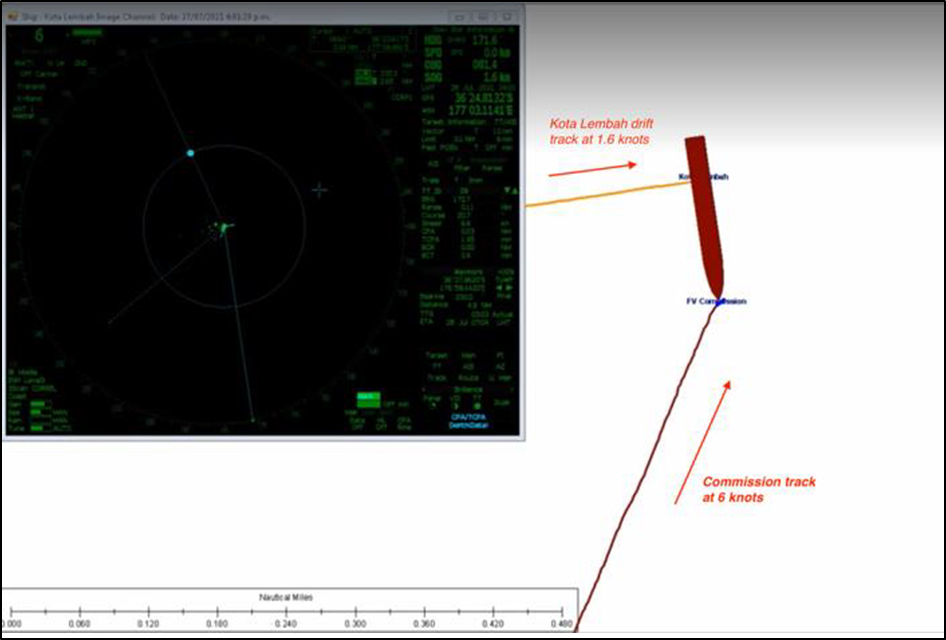

- At 0310 the AB reported to the second mate a small vessel (the F.V. Commission) 6–7 NM away and fine (relates to direction – at a small angle to starboard of the ship’s heading) on the starboard bow. At 0323 the AB began plotting the F.V. Commission on the radar (using the Automatic Radar Plotting Aid (ARPA) feature on the radar) when it was about 3.8 NM away.

- At 0330 a second watchkeeping AB took over the shift from the first. The first AB told the second AB about the F.V. Commission, which was by then about 3.1 NM away and still on the starboard bow. The second AB reported to the second mate that the F.V. Commission was showing a small Closest Point of Approach (CPA).

- The second mate was not concerned. Having noted the F.V. Commission was doing about 6 knots, the second mate assumed that it was a fishing vessel. The second mate’s expectation was that fishing vessels usually altered course and would keep out of the Kota Lembah’s way, especially as the ship was drifting. Meanwhile the second AB was using a red laser pointer directed at the F.V. Commission to warn its crew of their presence.

- At 0350 the second mate became concerned that the F.V. Commission was getting closer and did not appear to be altering course.

- At 0355 the chief officer arrived on the bridge to begin taking over the watch from the second mate. The chief officer spent a few minutes familiarising himself with the ship’s situation, and then went with the second mate to the electrical equipment room behind the bridge to investigate a water leak that had developed in there during the night.

- At 0358 both were back on the bridge and the chief officer asked about the F.V. Commission, which was by then 0.5 NM away and still closing.

- At 0401 they lost sight of the F.V. Commission in the blind sector ahead of the ship caused by the container stow. At this distance the ship’s radar lost definition of the target and any displayed data became unreliable, and they were beginning to wonder what the F.V. Commission’s intentions were. They were more concerned about the possibility that the F.V. Commission’s crew might be attempting to board the Kota Lembah, rather than colliding with them.

- At 0401:40 the F.V. Commission collided with the Kota Lembah, but the bridge crew said they did not see, hear or feel the collision. The chief officer and second mate sent the AB forward with a radio to investigate, while each went to a different bridge wing in an attempt to see what was occurring at the bow.

- At about 0405 the F.V. Commission emerged from the Kota Lembah’s port bow and remained in the vicinity for about 10 minutes. The bridge crew then saw it heading away from their ship towards the west. They made no attempt to contact the F.V. Commission. Nothing was recorded in the bridge logbook and the master was not informed.

- The Kota Lembah resumed its voyage to Auckland the following day and berthed at Auckland on 30 July 2021.

Site examination

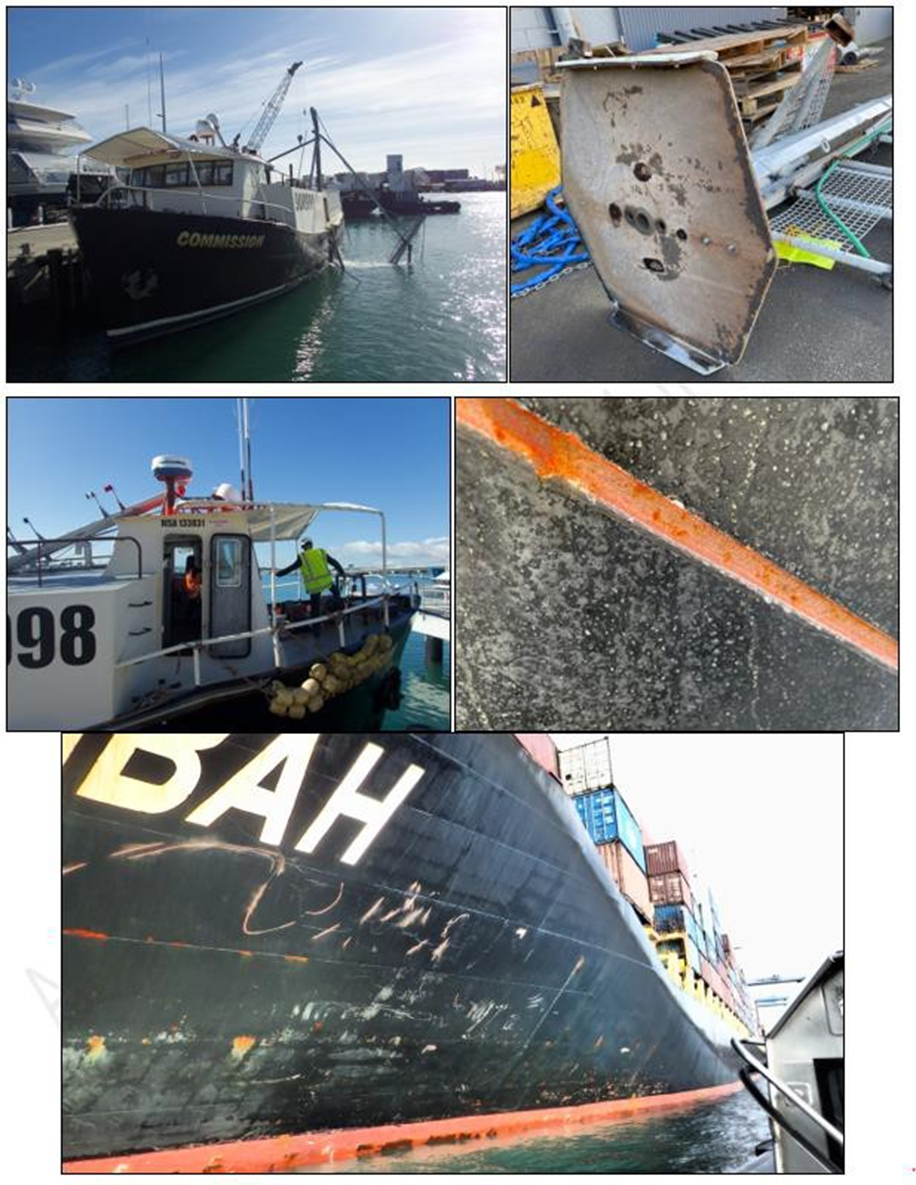

- Damage to the F.V. Commission was confined to the stabiliser arm and the upper wheelhouse structure.

- The stabiliser arm was bent around the point where it struck the stem of the Kota Lembah’s bow, with black paint transfer marks on many parts of the structure. The above-water area of the Kota Lembah’s hull is black. Red paint transfer marks were evident on the ‘foot’ of the stabiliser, which would have been below the sea surface at the time of the collision. The colour of this paint was consistent with the colour of the boot-topping and/or antifouling paint observed on the Kota Lembah’s hull.

- The top of the wheelhouse was scattered with black paint flakes. The main mast housed an array of navigation lights and communication antenna. The mast was broken off at base level. Several other standalone antennae were also damaged.

- The Kota Lembah suffered deep gouging of the paintwork under the starboard bow but was otherwise undamaged (refer to appendix 1 for photographs).

- The voyage data recorder from the Kota Lembah and the GPS from the F.V. Commission were downloaded and used to recreate the circumstances of the collision.

Other relevant information

Watchkeeping

- The F.V. Commission was under 24 metres in length. Under Maritime Rules Part 31 Crewing and Watchkeeping, the minimum manning requirement was a certified skipper and a certified engineer. In this case the skipper was certified as both skipper and engineer. The skipper was the only person on the vessel who had received formal training from an approved training provider in keeping a navigational watch.

- Maritime Rules 31 (Maritime Rules Part 31.85 Fishing Vessels Within the Inshore Fishing Limits or Fishing Vessels <24 Metres in Length Beyond Fishing Limits But Within Coastal or Offshore Limits) states how the “owner and master of the ship and any person engaged in navigational watchkeeping duties on the ship must take account of the standards for navigational watch keeping”, which are defined in the International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Fishing Vessel Personnel (STCW-F).

- The rule also states that the master must ensure that any watchkeeping arrangements are adequate to maintain a safe watch. Chapter IV of the STCW-F describes the suitable arrangements of a navigational watch and states that a lookout must be maintained in compliance with the Collision Regulations (COLREGS) (the International Regulations for Preventing Collision at Sea 1972).

- Section 5 of the F.V. Commission’s Maritime Transport Operator Plan (MTOP) says the owner/operator is committed to arrange for training of a crew member in the key functions of operating the vessel in a safe manner in the event the skipper becomes incapacitated. The MTOP also states that it is the responsibility of the operator and skipper that a refresher training regime is in place to ensure that the relevant competency levels are being maintained.

- The F.V. Commission’s MTOP was silent on watchkeeping standards altogether, and it did not refer to training in watchkeeping for unqualified deckhands.

- The two deckhands on board held no formal qualification in watchkeeping. Although they were not engaged in watchkeeping duties leading up to the collision, they were however made to keep watches when the F.V. Commission was transiting to and from and in between fishing areas. When interviewed they were unable to demonstrate any knowledge of the COLREGS.

Analysis Tātaritanga

Introduction

- It was dark but the visibility was clear when the Kota Lembah and F.V. Commission collided. The crew of both vessels had detected the presence of the other in ample time to assess the risk of collision and take the necessary action to avoid each other.

- The following analysis discusses the circumstances resulting in the collision and, in particular, the poor standard of watchkeeping on both vessels and the standards of watchkeeping on smaller fishing vessels in general.

- The analysis also discusses the issue of fatigue and how it about as likely as not was a factor contributing to the collision.

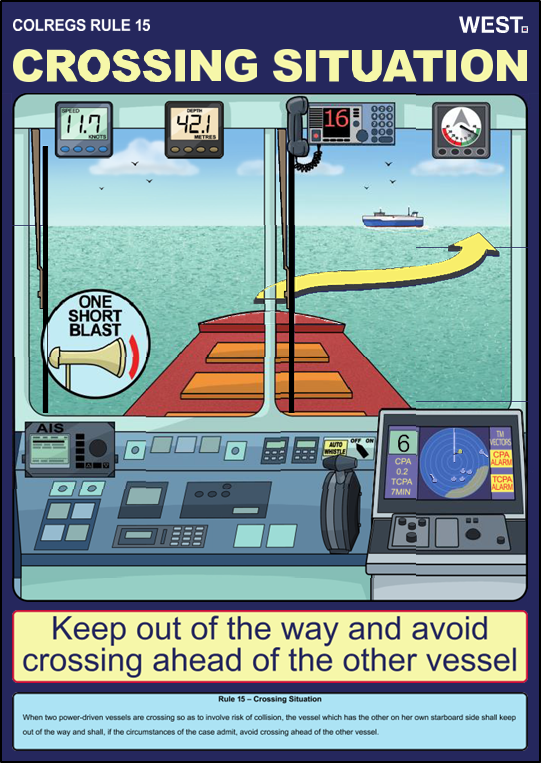

The Collision Regulations

- The International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, known as the COLREGs, were introduced by the International Maritime Organization in 1972. The COLREGs set out, among other things, the ‘rules of the road’ or navigation rules to be followed by vessels and other vessels at sea to prevent collisions between two or more vessels. The COLREGs are derived from a multilateral treaty called the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea.

- The COLREGS have been given effect in New Zealand through Maritime Rules Part 22 Collision Prevention. Part 22 applies to all New Zealand ships, including fishing ships, wherever they are, and to foreign ships while in New Zealand waters (‘New Zealand waters’ are defined in the Maritime Transport Act 1994 and extend out to the territorial sea). The collision occurred in New Zealand’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), but outside the territorial sea (the territorial sea extends out to 12 NM from the New Zealand coast, while the EEZ extends out to 200 NM from the coast), so Part 22 applies to the F.V. Commission but the COLREGS apply to the Kota Lembah, being a foreign flagged vessel. There is no difference of any substance for the purposes of this investigation between the Maritime Rules, Part 22 and the COLREGS. For simplicity, the term COLREGS is used for both vessels.

- This collision occurred in open waters where no other special rules applied. Fishing vessels that are engaged in fishing have special considerations under the COLREGS. The F.V. Commission was engaged in fishing and was displaying the appropriate lights to show that it was, being two all-round lights in a vertical line, the upper being red and the lower being white (COLREGS Rule 26 (c)(i) Fishing Vessels). As the F.V. Commission was underway (not at anchor, or made fast to the shore, or aground) it was also displaying red and green side lights and a stern light (see figure 6).

- The Kota Lembah was drifting with its engines stopped. Nevertheless, under the COLREGS it is still considered to be a power-driven vessel underway and was therefore required to follow the COLREGS and take the appropriate action to avoid a collision. The Kota Lembah was displaying the appropriate lights for a ship of its size, this being one forward and one aft masthead light, each located on the centreline of the ship, with the aft being higher than the forward, as well as red and green sidelights and a stern light. These navigation lights are often referred to colloquially as steaming lights.

- In addition to the standard navigation lights the master had instructed the watchkeeping officers to turn on the working lights illuminating the aft mooring station and the deck-level lights along the main cargo deck on each side of the vessel. The master ordered this to indicate to other vessels that the Kota Lembah was drifting. The COLREGS state that “…no other lights shall be exhibited, except such lights as cannot be mistaken for the lights specified in [the] Rules or do not impair their visibility or distinctive character” (COLREGS Rule 20(b) Application).

- It could not be established whether exhibiting these additional lights would have impaired the visibility of the steaming lights. However, in the context of this collision they were immaterial because the F.V. Commission’s skipper made no attempt to sight the Kota Lembah after noticing it on the radar at 4 NM distance and did not visually see it until after the collision.

- The Kota Lembah was drifting sideways at about 1.6 knots under the influence of the westerly wind, while its heading was broadly in a south direction. The F.V. Commission was approaching the Kota Lembah from the ship’s starboard bow at a speed of about 6 knots. This is considered a crossing situation under the COLREGS, with the Kota Lembah being the give-way vessel. Also, the F.V. Commission was engaged in fishing, which meant the Kota Lembah must not impede it.

- The Kota Lembah bridge crew had detected and were plotting the progress of the F.V. Commission on their radar. They had identified the F.V. Commission as a crossing vessel, but it did not occur to them that they needed to take action to give way (refer to figure 7). The bridge crew were working on two false assumptions. First, that because their vessel was drifting this entitled their ship to be given way to by others. Secondly, because the F.V. Commission was probably a fishing vessel, it would give way to them by virtue of their size.

- To exacerbate the matter, the Kota Lembah’s engine had been put on 30 minutes notice, which meant that the bridge crew could not have manoeuvred as required by the COLREGS, even if they intended to. The master had chosen 30 minutes notice with avoidance of grounding in mind. The requirement to manoeuvre in accordance with the COLREGS had not been considered.

- On board the F.V. Commission, little thought had been given to manoeuvring in accordance with the COLREGS. The skipper had detected the presence of the Kota Lembah when 4 NM away but made no attempt to sight or plot the vessel. The skipper was working on the assumption that because they were fishing, everything else would keep out of their way.

- Although the F.V. Commission was the ‘stand-on’ vessel, the COLREGS are clear that despite the Kota Lembah being the give-way vessel, as soon as it became apparent to the F.V. Commission that the Kota Lembah was not taking appropriate action as required by the rules, the F.V. Commission may take action to avoid collision by its manoeuvre alone.19 This is often referred to as the ‘both-to-blame clause’, which means that a collision is rarely solely attributable to one vessel.

- However, the skipper had neither sighted nor plotted the Kota Lembah, so they had little idea what the target on the radar was or whether a risk of collision existed. Also, the F.V. Commission making last-minute evasive manoeuvres was not possible because there was nobody in the wheelhouse in the minutes leading up to the collision. The deckhands were on deck focused on setting the longline and the skipper was in the engine room transferring fuel. Nobody was keeping watch.

- The F.V. Commission’s skipper assumed that as the F.V. Commission was fishing, other vessels would keep out of its way. Similarly, the bridge crew on the Kota Lembah assumed, contrary to the COLREGS, that the F.V. Commission would avoid colliding with their vessel.

- Under these circumstances, and with the coincidental crossing of paths, the collision was inevitable.

Fatigue management on board fishing vessels

- When undertaking commercial fishing operations, the crew are required to comply with the Health and Safety Work Act 2015 (HSWA). HSWA obligations are overseen by Maritime New Zealand (MNZ) (in addition to administering the Maritime Transport Act (1994), MNZ is charged with the oversight and regulation of the HSWA on board commercial fishing craft) and operators are required to provide evidence of compliance with the HSWA as part of their Maritime Safety Operating System (MOSS), as documented in their MTOP.

-

The HSWA identifies fatigue as a potential risk that is required to be managed. The responsibility for managing fatigue is shared between those conducting or in charge of the business and those employed to carry out the work. Regarding maritime activity, MNZ gives the following interpretation (Health and Safety: A Guide for Mariners, MNZ):

Maritime operators and masters both have duties under HSWA. Some of these duties overlap while others are different. In practice, the maritime operator and the master must work together to meet their duties.

Although the duties of a maritime operator and a master are slightly different, they address the same or similar things with regard to health and safety. The duties are shared or partially shared and the degree of responsibility depends on the circumstances of a given situation.

The duties of the maritime operator and the master apply at the same time. The master is in control of the ship when it is at sea. While the operator may not be present, they must still fulfil their duty to ensure that the ship operates safely. The operator cannot contract out or transfer their duties to the master or anyone else.

In practice, the operator must make appropriate arrangements with the master to ensure that the operator’s duties are met when the ship is at sea. For example, the duties of an operator include putting in place processes to manage risks and hazards.

-

Regarding commercial fishing activity, MNZ provides advice for individuals employed on fishing vessels about how fatigue can be recognised and mitigated while at sea. MNZ also provides detailed guidance for fishing vessel owner/operators on how to formulate a Fatigue Management Plan specific to their operation. Recommended rest is outlined as follows:

A number of things can lead to fatigue, including long or irregular work hours, sleep disruption, extreme environmental conditions, physical and mental work demands, and stress. And without a doubt, the best remedy is sleep. So how much rest is needed?

The standards set by the International Labour Organisation Convention 180 are: either a maximum working limit of 14 hours in any 24-hour period and 72 hours in any seven-day period, or a minimum of 10 hours’ rest in any 24-hour period and 77 hours’ rest in any seven-day period. While these rules apply to international vessels, they give you a good indication of what are thought to be safe levels of rest.

Fatigue management on board the F.V. Commission

Safety issue – Although the MTOP referenced fatigue as a significant on board hazard, there was no evidence that the operator was properly auditing the actual application of fatigue management on board the F.V Commission.

- Section 4 of the F.V. Commission’s MTOP contained the Health and Safety Policy for the vessel. The policy detailed the responsibilities of those involved in the vessel operation, as well the various measures to be undertaken to comply with the HSWA. This included safety procedures to be adhered to on board the vessel, and a means by which to identify and manage hazards.

- The MTOP referenced fatigue as a ‘significant’ on board hazard. Fatigue was recorded as such in the F.V. Commission’s Hazard Identification Register. The skipper was listed as the person responsible for managing this hazard. The register noted that while fatigue could not be eliminated, steps could be taken to minimise its impact. The documented control by which to manage fatigue on board was stated as: maintain proper rest hours.

- According to section 7 of the MTOP, one of the six Standing Orders for the vessel was: make sure crew are not fatigued while working. Section 4 listed examples of how to recognise the symptoms of alcohol or drug use or fatigue (It is well established that the performance impairments caused by fatigue are similar to those caused by alcohol (Williamson & Feyer, 2000; Falleti et. al., 2003; Lowrie & Brownlow, 2020; Lowrie, J., 2020)):

- Irritable

- Uncommunicative, or unclear when they speak

- Slur or muddle their speech

- Forget things quickly

- Cut corners when completing tasks

- Take out of the norm risks

- Miscalculate distance and time

- Clumsiness

- Obviously sleepy.

- The MTOP falls well short of addressing the issue of fatigue. The statement ‘maintain proper rest hours’, while appropriate, was not achievable because insufficient resources were provided to achieve the desired outcome. The MTOP listed the skipper as being responsible for managing the hazard of fatigue, and yet they were the most vulnerable to succumbing to it.

- While statements in a manual may well give the impression that the matter has been managed, a good audit would test to see how it was being achieved. This is discussed further in the following section.

- A recommendation has been made to the F.V. Commission’s owner/operator to review and amend the MTOP for management of fatigue on board.

Resourcing the F.V. Commission adequately to minimise the risk of fatigue and meeting good industry watchkeeping standards

Safety issue – There are indications that the requirement for fishing deckhands to be sufficiently trained in watchkeeping is not being fully adhered to by some owners of the New Zealand under 24-metre fishing fleet.

- The minimum manning requirements for the F.V. Commission referred to in previous sections are, as the name suggests, an absolute minimum. The owner and skipper, however, are responsible for ensuring there is sufficient crew on board commensurate with the nature and length of the voyage. This responsibility extends not only to ensuring there are sufficient crew on board to adequately manage the risk of fatigue, but also that those crew used for watchkeeping are adequately trained to keep a safe watch.

- The two deckhands did not have sufficient knowledge of the COLREGS to keep a safe watch, yet they routinely kept watch to enable the skipper to sleep when the F.V. Commission was in transit and not fishing. Also, it was common practice for everyone on board to sleep while the F.V. Commission was drifting and displaying the lights for a ‘vessel not under command’ (two all-round red lights, one vertically above the other – the definition of a vessel not under command is a vessel which through some exceptional circumstances is unable to manoeuvre as required by the COLREGS and is therefore unable to keep out of the way of another vessel). Neither practice was compliant with the COLREGS or Maritime Rules.

- There is anecdotal evidence that these practices are not uncommon amongst New Zealand’s fleet of smaller fishing vessels.

- The F.V. Commission had been at sea continuously for some five days when the collision occurred. The skipper had managed to obtain some sleep over that time by engaging in one or other of these non-compliant practices. Nevertheless, the skipper often still struggled to get sufficient sleep.

- The collision occurred at approximately 0400 hours which, given the description of the crew’s sleep/wake cycles before the event, places the occurrence within the time the skipper would have been experiencing a natural dip in biological alertness level. Circadian rhythm is an individual’s natural sleep/wake cycle across 24 hours; the most significant natural dip in alertness levels being between 0300 and 0500 hours.

- At the time of the collision, the F.V. Commission’s skipper had been awake for approximately 20 hours. This 20 hours was a mix of high physical activity and mental planning, with the occasional brief period of relaxation as the F.V. Commission located the setline, hauled it in and processed the catch. This had been preceded by a sleep period of approximately 5–6 hours between 0230 and 0830 on the morning of 27 July. Periods of extended wakefulness will impact on human performance, and while the exact threshold for performance decrement will vary, there is broad agreement that impairments will begin to occur after 17 hours of awake time (impairments range from: psychomotor hand-eye coordination after 17 hours of awake time (Dawson & Reid, 1997); significant visual perceptual, complex motor and simple reaction tasks after 19 hours of awake time (TSB, 2014); and being awake for at least 24 hours is deemed equal to having a blood alcohol content of 0.10% (Dawson & Reid, 1997; Lamond & Dawson, 1999)).

- The presence of a ship in the immediate area where the F.V. Commission was fishing was a potential threat that should normally have been assessed and monitored. The skipper appears to have ignored the threat in favour of focusing on the fishing task at hand. Cutting corners and taking or accepting out of norm risks are two symptoms of tiredness or fatigue. Given his awake/sleep pattern it is therefore about as likely as not that fatigue was a factor contributing to the accident.

- Maritime Rules Part 31 attempts to strike a balance between requiring smaller fishing vessels to carry so many crew members that they become economically unviable and achieving adequate navigation safety. There is provision for owners and skippers to train unqualified deckhands to a level of skill where they can keep a safe navigation watch. However, the F.V. Commission’s MTOP makes no reference to training deckhands in watchkeeping, and clearly the two deckhands on board had received no such training.

- This situation is not dissimilar to that on board the fishing vessel Leila Jo when it collided with the bulk carrier Rose Harmony off the port of Lyttelton in January 2020 (TAIC report MO-2020-201, Collision between bulk carrier Rose Harmony and fishing vessel Leila Jo, off Lyttelton, 12 January 2020).

- Following that inquiry, a recommendation was made to MNZ to use its audit function to review the adequacy of watchkeeping training programmes for upskilling unqualified deckhands to a level that meets good industry practice and complies with the requirements of Maritime Rules Part 31 (refer to section 5 of this report). The recommendation is equally applicable to this occurrence.

Findings Ngā kitenge

- The Kota Lembah was the ‘give-way’ vessel under the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGS) – the F.V. Commission was the stand-on vessel.

- The Kota Lembah did not, and could not, take the correct action required under the COLREGS because its engine was not readily available for manoeuvring.

- The F.V. Commission did not take the correct action required under the COLREGS when the Kota Lembah failed to give way because: there was nobody in the wheelhouse at the time of the collision; they had not previously maintained a proper lookout; and they had not established whether a risk of collision existed between it and the Kota Lembah.

- The standard of watchkeeping on board the F.V. Commission did not meet the standards required in Maritime Rules Part 31 Crewing and Watchkeeping, neither in the period leading up to the collision, nor during routine fishing operations.

- The standard of watchkeeping on board Kota Lembah in the period leading up to the collision did not give full effect to the COLREGS and was not consistent with good industry practice.

- It is about as likely as not that the F.V. Commission skipper’s decision-making was to some degree influenced by the effects of fatigue in the period leading up to the collision.

- The skipper was the only qualified watchkeeper on board the F.V. Commission and the two deckhands were not sufficiently trained to conduct a watch, which meant it was almost certain that the F.V. Commission would not be able to achieve full compliance with the COLREGS and Maritime Rules Part 31 without the skipper becoming chronically fatigued during routine fishing operations.

- There is mounting evidence that a compromise in crewing levels aimed at keeping small fishing vessel operations economically viable is resulting in fishing crews either not achieving full compliance with national and international legislation or operating when fatigued. Either way, the result will be a higher risk of these vessels being involved in collisions or groundings.

Safety issues and remedial action Ngā take haumanu me ngā mahi whakatika

General

- Safety issues are an output from the Commission’s analysis of factors that have contributed to the occurrence. They typically describe a system problem that has the potential to adversely affect future operations on a wide scale.

- Safety issues may be addressed by safety actions taken by a participant, otherwise the Commission may issue a recommendation to address the issue.

- Recommendations are made to persons or organisations that are considered the most appropriate to address the identified safety issues.

- In the interests of transport safety, it is important that safety actions are taken (or any recommendations are implemented) without delay to help prevent similar accidents or incidents occurring in the future.

- Two new safety issues were identified in this investigation:

- Although the MTOP referenced fatigue as a significant on-board hazard, there was no evidence that the operator was properly auditing the actual application of fatigue management on board the F.V Commission.

- There are indications that the requirement for fishing deckhands to be sufficiently trained in watchkeeping is not being fully adhered to by some owners of the New Zealand under 24-metre fishing fleet.

Previous recommendation 003/21 made to Maritime New Zealand

Safety issue – There are indications that the requirement for fishing deckhands to be sufficiently trained in watchkeeping is not being fully adhered to by some owners of the New Zealand under 24-metre fishing fleet.

- On 27 May 2021, the Commission recommended that MNZ, when assessing or auditing operator safety systems for fishing vessels, review the adequacy of watchkeeping training programmes for upskilling unqualified deckhands to a level that meets good industry practice and complies with the requirements of Maritime Rules Part 31 (003/21).

-

On 16 June 2021 MNZ replied:

We agree with this recommendation. The majority of fishing vessels to which this recommendation applies are covered by mandatory safety systems such as the Maritime Operator Safety System (MOSS) under Maritime Rules Part 19. Fishing vessels under 6m may instead have Safe Operating Plans (SOP) under Maritime Rules Part 40D.

MNZ has a rigorous entry-control process for new commercial operators entering the MOSS and SOP safety systems, including obtaining evidence and undertaking a site visit to ensure, amongst other safety-critical issues, that fishing vessels are manned by appropriately trained and qualified masters and crew as required by Maritime Rules Part 31.

Ongoing compliance, under both safety systems, is assured through regular statutory audits of operators under section 54 of the Maritime Transport Act 1994, as well as other focused inspections and investigations as needed.

In response to this recommendation from the Commission, MNZ will consider how to incorporate this recommendation into our audit processes within the MOSS and SOP safety systems. Specifically, we will consider implementing a quality assurance process to specifically monitor operators’ watchkeeping training programmes for unqualified deckhands. We will aim to provide an update on our response to this recommendation in the first half of 2022.

-

On 23 February 2022, MNZ provided updated information on its response as follows (in part):

MNZ conducted 122 face-to-face MOSS and [Safe Operational Plan] audits from August to December 2021. Four cases were identified where unqualified deckhands were required to undertake watchkeeping duties. Maritime Officers asked specific questions relating to good watchkeeping practices. These questions were designed to assess compliance with Maritime Rules Parts 22, 3127 and 9128. The Maritime Officers provided comments and advice to the operators, depending on the response to these questions. Maritime NZ is currently considering options to further address issues related to crew fatigue and watchkeeping on fishing vessels, including targeted stakeholder engagement and a potential review of Maritime Rules Part 31. In the meantime, an article about watchkeeping was also published in the October 2021 issue of our public newsletter, SeaChange.

Recommendations Ngā tūtohutanga

General

- The Commission issues recommendations to address safety issues found in its investigations. Recommendations may be addressed to organisations or people, and can relate to safety issues found within an organisation or within the wider transport system that have the potential to contribute to future transport accidents and incidents.

- In the interests of transport safety, it is important that recommendations are implemented without delay to help prevent similar accidents or incidents occurring in the future.

New recommendations

Recommendation to the owner of the ‘F.V. Commission’

-

On 23 March 2022, the Commission recommended that Oceanic Fishing Limited enhance its training system to upskill deckhands in watchkeeping practices that meet the minimum requirements of Maritime Rules Part 31 and adequately reduce the risk of accidents and incidents resulting from poor watchkeeping practices and fatigue. (002/22)

On 11 April 2022, Oceanic Fishing Limited replied, in part:

We have engaged a maritime specialist to review our MOSS system with view to making improvements to our operation and MOSS system.

-

On 23 March 2022, the Commission recommended that Oceanic Fishing Limited have appropriate fatigue management policies and procedures in place and a method to audit these to ensure that they are being applied effectively on board vessels in their fleet. (003/22)

On 11 April 2022, Oceanic Fishing Limited replied, in part:

We have had a meeting with our skippers and crew and discussed the importance of following our rules and procedures for managing fatigue, including limiting hours of work and taking breaks.

Recommendation to the operator of the ‘Kota Lembah’

- On 23 March 2022, the Commission recommends that Pacific International Lines disseminate the findings and lessons arising from this report to its fleet and audit the navigational practices of its fleet for compliance with the COLREGS at all times. (004/22)

Key lessons Ngā akoranga matua

- The International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea provide the mandated standard to be followed by all vessels at sea to prevent collisions of two or more vessels. The risk of collisions will inevitably be high if they are not adhered to by one or more vessels.

- All vessels have a part to play in preventing collisions at sea, regardless of whether they are the stand-on or give-way vessel.

- Making assumptions based on no or scanty information about the intentions of other vessels is high-risk, which will inevitably result in collisions at sea.

- Fatigue is a significant risk that must be properly managed during fishing operations, including providing sufficient resources on board commensurate with the length of the voyage and type of fishing operation.

Data summary Whakarāpopoto raraunga

Details

Data summary Whakarāpopoto raraunga

Details

Conduct of the Inquiry He tikanga rapunga

- On 28 July 2021, MNZ notified the Commission of the occurrence. The Commission subsequently opened an inquiry under section 13(1) of the Transport Accident Investigation Commission Act 1990 and appointed an Investigator-in-Charge.

- Preliminary inquiries identified the container ship Kota Lembah as potentially the other vessel involved in the reported collision with the F.V. Commission.

- The Commission notified the Kota Lembah’s Flag State Singapore of the ship’s potential involvement in the accident. Singapore declined to investigate but offered to assist the Commission in its inquiry as required.

- The Commission issued three protection orders. The first protection order was to prevent the tampering or altering of any evidence on board the F.V. Commission. The second protection order was to download and protect the voyage data recorder on board the Kota Lembah. The third protection order was to prevent tampering with any parts of the ship’s external hull and paintwork.

- On 29 July 2021, a team of three investigators travelled to Tauranga to conduct the site investigation at the F.V. Commission and interviewed all of the people on board at the time of the collision, as well as the vessel’s owner.

- On 30 July 2021, the three investigators relocated to Auckland to meet the Kota Lembah. They interviewed the master and key watchkeeping personnel on duty at the time of the collision and collected relevant documents. The Kota Lembah’s voyage data recorder was successfully downloaded.

- On 19 January 2022, the Commission approved a draft report for circulation to nine interested persons for their comments. Submissions were received from five interested persons. Any changes as a result of those submissions have been included in the final report.

- On 23 March 2022, the Commission approved this final report for publication.

Glossary Kuputaka

- Aft

- At, near or towards the stern of a vessel

- Bow

- The front of a vessel

- Bridge

- The place on a ship from which the vessel is normally controlled

- Circadian rhythm

- The circadian rhythm is a well-recognised physiological phenomenon. The time that an accident occurs is commonly analysed as part of investigative processes. (NTSB, 2006; TSB, 2014)

- Centreline

- An imaginary line running from forward to aft in the middle of a vessel

- List

- A lean to one side caused by an uneven distribution of weights within a vessel

- Port

- The side of a vessel that is left when facing forward

- Starboard

- The right side of a vessel when the viewer is facing forward

- Watertight integrity

- A portion of a vessel, normally below the main working deck, is sealed off to provide buoyancy. If a vessel has watertight integrity it means these spaces have not been breached

- Wheelhouse

- Enclosed area on a ship from which it is steered

Bibliography Rārangi pukapuka

Falleti M., Maruff P., Collie A., Darby D. G., McStehen M. (2003) Qualitative similarities in cognitive impairment associated with 24 h of sustained wakefulness and a blood alcohol concentration of 0.05%. J. Sleep Research, 12, 265-274.

Lamond N. & Dawson D. (1999) Quantifying the performance impairment associated with fatigue. J Sleep Res. 1999;8(4):255-62.

Lowrie J., Brownlow H. The impact of sleep deprivation and alcohol on driving: a comparative study. BMC Public Health 20, 980 (2020)

Williamson A. & Feyer A. (2000). Moderate sleep deprivation produces impairments in cognitive and motor performance equivalent to legally prescribed levels of alcohol intoxication. Occupational and environmental medicine, 57(10), 649–655.

National Transport Safety Board (2006). Methodology for investigating operator fatigue in a transportation accident. NTSB.

Transport Safety Board (2014). Guide to Investigating sleep-related fatigue. TSB: Quebec.

Appendix 1. Photographs of damage to the F.V. Commission and Kota Lembah

Related Recommendations

The Commission recommended that Oceanic Fishing Limited have appropriate fatigue management policies and procedures in place and a method to audit these to ensure that they are being applied effectively on-board vessels in their fleet.

The Commission recommends that Pacific International Line disseminate the findings and lessons arising from this report to its fleet and audit the navigational practices of its fleet for compliance with the COLREGS at all times.

The Commission recommended that Oceanic Fishing Limited enhance its training system to upskill deckhands in watchkeeping practices that meet the minimum requirements of Maritime Rule Part 31 and adequately reduce the risk of accidents and incidents resulting from poor watchkeeping practices and fatigue.