TAIC has resolved this inquiry, satisfied that the Interim Report published in May 2018 identified the salient safety issues, which Rolls-Royce had already addressed. The Commission’s early investigations prompted the engine manufacturer to improve its system for forecasting when the fatigue might happen. Affected turbine blades have been replaced in 99% of the global flying fleet.

Executive summary

On 5 December 2017, ZK-NZE, an Air New Zealand (the operator) Boeing B787-9 aeroplane, was being operated on a scheduled passenger flight from Auckland to Narita, Japan. During the climb phase of flight, the right engine started to ‘spool down’ or reduce in speed. The crew completed the necessary checks, and as a result shut down the engine and returned to Auckland International Airport without further incident. The Transport Accident Investigation Commission (Commission) opened inquiry AO-2017-009 into this occurrence. On 6 December 2017, ZK-NZF, another of the operator’s Boeing B787-9 aeroplanes, departed Auckland on a scheduled passenger flight to Buenos Aires, Brazil. During the climb phase of flight, the flight crew received engine ‘over temperature’ alerts for the right engine. The crew completed the necessary checks, reduced the thrust lever for the right engine to idle and returned to Auckland International Airport without further incident.

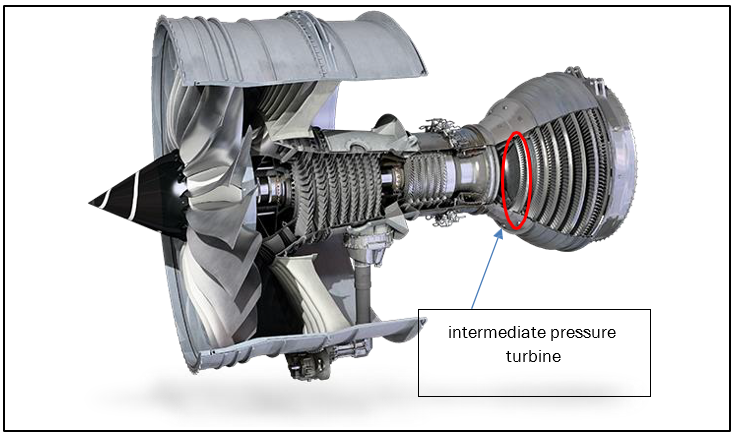

The Commission opened inquiry AO-2017-010 into this occurrence. Early in the investigation, the Commission was made aware of six previous Trent 1000 intermediate pressure turbine (IPT) blade separations.

Like the two New Zealand occurrences, the six failures had all involved the same type of IPT blade, and all had occurred soon after take-off or in the climb phase of flight. According to the engine manufacturer, the blade separations followed cracking in the blade shanks initiated by a ‘corrosion fatigue mechanism’. The manufacturer believed the mechanism involved a combination of blade design or construction, engine operational factors and environmental air contaminants.

Glossary Kuputaka

- Cycle

- One engine operation from start to stop

- Engine teardown

- The disassembly of an engine for detailed examination or repair

- Extended diversion time operations

- Flights by a twin-engine turbine powered aeroplane where the flight time (calculated at the cruise speed in still air with one engine inoperative) from any point on the route to a suitable alternative aerodrome is greater than 60 minutes.

- Maximum diversion time

- The maximum flight time, calculated at the cruise speed in still air with one-engine inoperative, that a multi-engine, turbine powered aeroplane on extended diversion time operations may be from a suitable alternate aerodrome.

- Offset

- Reduced life limit for the engine

- Shank

- That portion of the blade inserted into the turbine disk

Data summary Whakarāpopoto raraunga

Details

north of Auckland

35° 33´ south

173° 27´ east

Conduct of the inquiry He tikanga rapunga

- At 1100 on 5 December 2017 the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) advised the Transport Accident Investigation Commission (Commission) that a Boeing 787-9 aeroplane being operated by Air New Zealand Limited (the operator) had shut down one of its two Rolls-Royce Trent 1000 (Trent 1000) engines and had returned to Auckland.

- The Commission opened an inquiry and appointed an investigator in charge. The United Kingdom, being the State of engine manufacture, and the United States, being the State of aircraft manufacture, were notified and in accordance with Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, each appointed an accredited representative to the Commission’s investigation. The accredited representative of the United Kingdom appointed Rolls-Royce PLC (the engine manufacturer) as its adviser, in accordance with Annex 13.

- Commission investigators began the investigation at Auckland on 5 December 2017 with an inspection of the engine and damage to the airframe. The flight crew and pertinent staff from the operator’s engineering and operations divisions were interviewed. The flight recorders were downloaded.

- On 6 December 2017 another Boeing 787-9 operated by Air New Zealand experienced an engine anomaly. The flight crew reduced thrust on the affected Trent 1000 engine and returned to Auckland without further incident. The Commission opened a new inquiry for this incident with the same investigation team (Inquiry AO-2017-010, Boeing 787-9, ZK-NZF, engine operating anomaly, Auckland, 6 December 2017).

- On 22 February 2018 engine number 10231 from the first incident was received at Singapore Aero Engine Services Private Limited by an investigator from the Transport Safety Investigation Bureau of Singapore on behalf of the Commission. The preparation of the engine for a teardown examination was performed under the supervision of that investigator.

- Between 26 February and 2 March 2018, two Commission investigators oversaw the teardown of engine number 10231 by staff of Singapore Aero Engine Services and staff from the engine manufacturer. The affected turbine blade set was later sent to the Rolls-Royce laboratory at Derby, England, for detailed examination under the supervision of the accredited representative of the United Kingdom.

- On 19 March 2018 the teardown examination of engine number 10227 from the second incident began at Singapore Aero Engine Services under the supervision of a Commission investigator. The affected turbine blade set from this engine was also sent to the Rolls-Royce laboratory at Derby, England, for detailed examination under the supervision of the accredited representative of the United Kingdom.

- The Commission had various meetings with the operator, airworthiness managers with the CAA, and representatives of the engine manufacturer.

- On 6 March 2018 the Commission approved a draft interim report that was sent to interested persons for comment. The draft interim report raised safety issues that had been identified early in the inquiry, and included draft recommendations aimed at addressing those safety issues. The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and New Zealand CAA were invited to consider the draft recommendations. Submissions were received from Rolls-Royce, EASA and the CAA. The Commission considered these submissions and any changes as a result have been included in this interim report.

- EASA, the FAA and the CAA took safety actions that addressed the safety issues raised and met the intent of the draft recommendations. Therefore no final recommendations were issued.

- On 20 April 2018 the Commission approved the publication of this interim report.

- The inquiry into these two occurrences is continuing with the assistance of the organisations involved.

Factual information Pārongo pono

Introduction

- On 5 December 2017 a Boeing 787-9 aeroplane being operated by Air New Zealand on a flight from Auckland to Tokyo experienced an anomaly with one of its two Rolls-Royce Trent 1000-J2 (Package C) engines during the climb from Auckland. The flight crew shut down the affected engine (serial number 10231) and returned to Auckland without further incident.

- On 6 December 2017 another Boeing 787-9 operated by Air New Zealand experienced an engine anomaly while on climb from Auckland to Buenos Aires. The flight crew reduced thrust on the affected Trent 1000-J2 (Package C) engine (serial number 10227) and returned to Auckland without further incident.

- The operator’s flights were being conducted under procedures for extended diversion time operations (EDTO) (In the context of this report: a flight by a twin-engine, turbine-powered aeroplane where the flight time (calculated at the cruise speed in still air with one engine inoperative) from any point on the route to a suitable alternative aerodrome is greater than 60 minutes). EDTO enables flights across remote regions where a safe diversion to a suitable airport, for example after an engine failure, could take many hours. EDTO requires separate approvals from the appropriate authorities for the States of engine and aeroplane manufacture and the appropriate authority for the State of the aeroplane operator.

- In both cases an initial borescope inspection found that a turbine blade in the intermediate-pressure turbine (IPT) module had fractured and separated from the IPT disc (see Figure 1). Features were identified that indicated corrosion fatigue cracking had occurred. In the first occurrence the released blade caused significant damage to the IPT and low-pressure turbine modules. Small pieces of the turbine and stator blades were ejected through the exhaust nozzle and struck the leading edge of the right horizontal stabiliser. Some pieces also chipped the underside of the wing and the side of the fuselage towards the rear, but these did not cause significant damage. The damage in the second occurrence was mainly confined to the IPT module.

Background

- The Trent 1000 is one of two engine types fitted to the Boeing 787 aeroplane. The Trent 1000 was designed in the United Kingdom. It is manufactured in the United Kingdom and Singapore. The first variant was certified by EASA in 2007. The type certificate data sheet for the Trent 1000 series of engines stated that the engines were “approved for ETOPS [extended twin operations] (ETOPS is the EASA equivalent term for EDTO) capability… for a Maximum Approved Diversion Time of 330 minutes” (EASA TC E.036). However, individual operators required approval from their civil aviation regulatory authorities before an aeroplane-engine combination could conduct ETOPS (or EDTO) flights.

- The Boeing 787 was designed, and is largely manufactured, in the United States. The FAA certified the Boeing 787-9 in June 2014, and approved the aeroplane fitted with Trent 1000-J2 (Package C) engines for 180 minutes of EDTO from the outset. This was later extended to 330 minutes (specific regulatory approval was still required before an operator could conduct any EDTO flights).

- The operator was a launch customer for the Boeing 787-9. As the operator gained experience with the type, the CAA had approved progressively longer maximum diversion times (the maximum flight time, calculated at the cruise speed in still air with one engine inoperative, that a multi-engine, turbine-powered aeroplane on EDTO may be from a suitable alternative aerodrome). for EDTO. On 21 September 2016 the operator had gained approval for EDTO up to 330 minutes. The operator is one of two known to the Commission to have regulatory approval for 330 minutes of EDTO.

-

At the time of these incidents the manufacturer had a management and modification programme for a seperate issue – cracking of blades from the intermediate-pressure compressor (at the front of the engine).

IPT blade cracking

- According to Rolls-Royce there had been six in-flight IPT blade separations in Trent 1000 engines worldwide before the Air New Zealand incidents. All eight incidents occurred during the take-off or climb phase of flight when engines are subjected to the highest stress (an incident this early in a flight does not involve EDTO considerations and will likely result in an uneventful return to the departure airport). According to the engine manufacturer the blade separations had followed cracking in the blade shank (the portion of the blade inserted into the turbine disc) that had been initiated by corrosion. The engine manufacturer said it was likely that a combination of environmental and operational factors had been involved and that these could have been operator specific.

- To correct the corrosion fatigue issue, the engine manufacturer published a service bulletin (Non-Modification Service Bulletin Trent 1000-72-AJ575, initially issued November 2016) to manage the replacement of all the blades in the single-stage IPT module with redesigned blades made from a different alloy and with an improved corrosion-protective coating. The modifications could only be carried out at approved overhaul facilities. Due to the large number of engines that need modification, the engine manufacturer instituted a risk mitigation programme called the Corrosion Fatigue Lifing (CFL) model. The model predicted the crack propagation in blades and the time (in engine cycles (a cycle is one engine operation from start to stop)) when the relevant engines had to be removed from the aeroplane for modification.

Corrosion Fatigue Lifting model

- The CFL model was developed by the engine manufacturer from material fatigue theories and laboratory analyses of failed blades and blade sets already removed during the modification programme. The model took engine health monitoring data for every Trent 1000 engine and assessed the operational and environmental experiences so that a prediction could be made of the operating cycles before a corrosion fatigue crack in an IPT blade in that engine reached a nominal failure point. A reserve margin was applied to determine the cycle count when the engine should be removed from service (airlines are given 80 cycles’ advance notice to allow scheduling of the engine change). This action was mandated by EASA airworthiness directive 2017-0056, dated 5 April 2017.

- The engine manufacturer emphasised that the CFL model was a “dynamically improving” model that adjusted cycle predictions for each operator and engine according to sampling and analysis results. This included the determination of ‘offsets’ (reduced life limits) specific to each operator. The engine manufacturer said that the raw model was applied globally and had not changed since May 2017. However, offsets have been modified according to the results of the ongoing engine sampling programme and the December 2017 incidents. The engine manufacturer explained that the model catered for corrosion fatigue cracks, which propagate at different rates from the theoretical rates used for mechanical fatigue. Therefore the model used empirical evidence to generate estimates of corrosion-fatigue-crack growth.

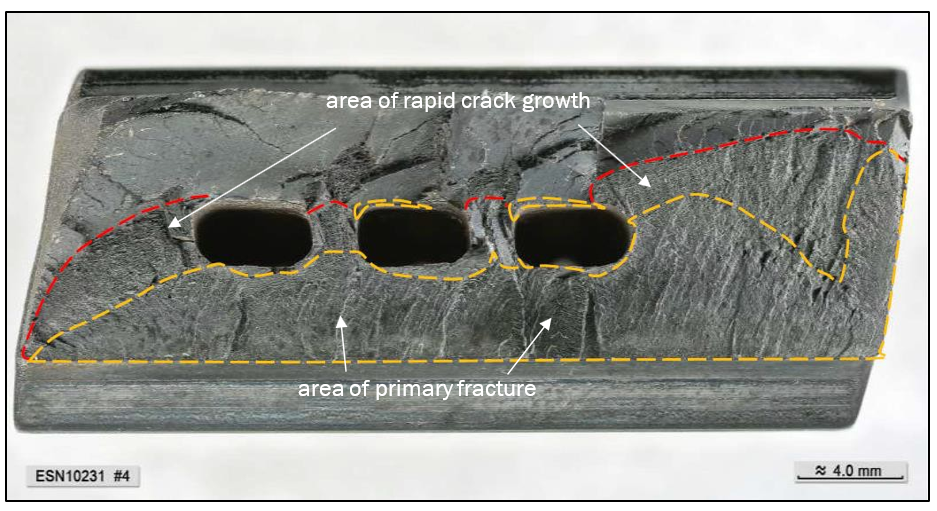

- The incidents in December 2017 with engine numbers 10231 and 10227 occurred at 1,545 and 1,453 cycles respectively, up to 12% earlier than the CFL-predicted cycles for the removal of the engines for modification. Therefore the CFL model failed to provide the intended conservative reserve margin before failure.

- In response to these unpredicted failures, the engine manufacturer recalculated the offsets for unmodified engines still in use, which increased the reserve margin and therefore would require earlier removal of those engines for modification. Air New Zealand also voluntarily reduced its maximum diversion time for EDTO to 240 minutes. On 21 December 2017 EASA issued emergency airworthiness directive 2017-0253-E, which required operators, independently of any CFL predictions, to de-pair (to de-pair is to ensure that two engines with similar cycle counts are not fitted to the same aeroplane) specified engines with high cycle counts in order to reduce the risk of a dual in-flight engine shut-down.

- The teardown examination of engine 10231 found that the corrosion fatigue crack in the failed blade was deeper than the model predicted for a critical crack (see Figure 2). Therefore the assumed crack progression rate may have been understated for that engine. Rolls-Royce said that similar crack depths had been seen on some other failed blades, but with a higher number of cycles. If a CFL offset of minus 400 cycles (until more operator-specific sampling and analysis data was available, the cycle count determined by the CFL model for engine removal was reduced by 400. Similar offset adjustments were made for other Trent 1000 operators for which there was limited in-service data) had been in place for the operator’s fleet before the incidents, both engines would have been removed from service before the blades failed (see Section 4, Safety actions).

Safety issues Ngā take haumanu me ngā mahi whakatika

- IPT blade release is a known problem with the Trent 1000 engines and is being managed under a service bulletin and a CFL model, which was produced by the engine manufacturer and approved by EASA. On 5 December 2017 engine number 10231, installed on Boeing 787-9 (registration ZK-NZE) was five cycles into its 80-cycle notice of removal when it suffered an IPT blade release. Less than 18 hours later, engine number 10227 on another of the operator’s Boeing 787-9 aeroplanes (registration ZK-NZF) had a similar event. The second engine had 192 cycles remaining until the CFL model scheduled removal. Both flights were being conducted under EDTO procedures.

- Because both blade failures occurred before the CFL model required the engines to be removed, the engine manufacturer modified the dynamic CFL model and applied offsets to increase the reserve margin for this operator’s engines, and for other engines for which there was limited in-service data.

-

The Commission’s investigation of these two incidents identified two related safety issues:

-

without operator-specific offsets being applied, the CFL model cannot reliably predict the point of blade failure, and thus cannot ensure that an engine with unmodified IPT blades will be removed from service well before a blade fails

- should an engine need to be shut down in flight, the remaining engine must be operated at a higher thrust level. If the remaining engine has unmodified IPT blades, there is an increased risk of that engine failing, which could mean an aircraft on an EDTO flight cannot reach its designated alternative aerodrome.

- The authorities involved in the manufacture and certification of the engine and aircraft type had been taking safety actions in response to previous turbine blade failures.

- At the time of the two incidents, no offset was applied to the CFL model predictions for the

- operator’s engines because there was insufficient blade sample data. In response to the two incidents, the manufacturer introduced a minus-400-cycle offset for the operator’s fleet and negative offsets for other operators for which there was insufficient sample data.

- In addition, EASA issued emergency airworthiness directive 2017-0253-E on 21 December 2017. The directive required the “de-pairing” of high-life engines, independently of the CFL model predictions, to further reduce the risk of a double in-flight engine shutdown.

- The engine manufacturer advised the Commission that the maximum depth of cracks on the failed IPT blades was 6.2 millimetres for engine 10231 and 5.9 millimetres for engine 10227. It advised that as these crack depths were in keeping with the CFL model predictions, it saw no need to again amend the baseline CFL model.

- On 15 March 2018 EASA advised the Commission that it had reviewed the CFL model and it was being provided with regular updates by the engine manufacturer. The model and the mandatory de-pairing of engines were subject to ongoing review “until full confidence in the CFL model is gained”.

- The Commission also suggested that EASA consider the extent to which unmodified Trent 1000 engines remained eligible for EDTO. EASA advised that its monitoring of ETOPS/EDTO was being reviewed periodically with the engine manufacturer, with a greater focus following the two recent events.

- The Commission gave notice to the FAA and the CAA of its suggestions to EASA. The CAA noted that the actions taken by the engine manufacturer and EASA had met the intent of the Commission’s suggestions.

- As at 19 April 2018 the FAA had not replied to the Commission’s notice (the NTSB, FAA and Boeing Aircraft Company later advised they had no additional comment to make). However, on 17 April 2018 the FAA issued airworthiness directive 2018-08-03. The directive was primarily in response to the different earlier issue arising from cracking in the compressor blades near the front of the engine. The airworthiness directive stated that the single-engine diversion time must not exceed 140 minutes. That action, in effect, also addressed the safety issue the Commission raised – of a potential dual in-flight engine shut-down for an aeroplane equipped with engines that have unmodified IPT blades.

Further lines of inquiry

- As at 19 April 2018, the IPT blade sets from engines 10231 and 10227 were undergoing further analysis at the engine manufacturer’s laboratory. This work was being overseen by the United Kingdom Air Accidents Investigation Branch, with regular updates being provided to the Commission.

- In an attempt to identify the source of the corrosion fatigue, Rolls-Royce was continuing to analyse the history of each of the failed engines. In addition to collecting flight data, a range of tests was being undertaken, including swabbing engines for any chemical residue.

- The Commission will review the operator’s engine management and flight procedures for factors that might have contributed to the early in-flight blade failures.

- After it has assessed the results of these further lines of inquiry, the Commission will determine whether it should take further action or make any recommendations.