A rail signal technician was potentially put at risk from rail traffic, unaware that the line was not protected. People didn't follow rules & procedures for everyone working on a safety-critical task to: share a clear understanding of the task and how everyone will do it. Wrong assumptions about nature of the signals task and how the technician was protected. Everyone should ask; don't assume.

Executive summary Tuhinga whakarāpopoto

What happened

- At about 1850 on Sunday 24 March 2019, a work group was completing rail track repairs in a protected work area that had been established in KiwiRail’s Westfield yard in Ōtāhuhu, Auckland. The protected work area was in the process of being disestablished before the work party departed from the site.

- The rail protection officer in charge of the site was approached by a signals technician who was required to carry out work within the protected work area.

- Unaware of the exact nature of the signals technician’s intended work, the rail protection officer lost situational awareness and allowed the technician into the protected work area without following the requirements prescribed in KiwiRail’s Rail Operating Rules and Procedures.

- As a result, the signals technician was not considered to be part of the work group and was therefore not accounted for using the lock-on procedure. The technician was still working within the protected work area when, without any prior knowledge, the electronic blocking protection was removed, putting the technician at risk from rail traffic.

Why it happened

- The Transport Accident Investigation Commission (Commission) found that it was very likely that a safe-working incident occurred as a result of the electronic blocking protection being removed at the rail protection officer’s request, while the signals technician was still working on the track.

- The Commission also found that the rail protection officer’s request to remove electronic blocking was likely due to the rail protection officer and the signals technician not utilising non-technical skills effectively to develop a shared mental model of the work to be undertaken by the signals technician. Had both parties communicated more effectively and agreed a work plan, it is highly likely that the incident could have been avoided.

- Neither party had a clear understanding of the other’s intentions, nor did each thoroughly question the other. Because the rail protection officer misunderstood the intentions of the signals technician, it was decided that the prescribed procedure was not required to be followed. This was contrary to KiwiRail’s Rail Operating Rules and Procedures and resulted in the omission of a key safety defence that could have prevented the incident occurring.

What we can learn

- The key lesson arising from the inquiry is that all personnel undertaking safety-critical roles should adhere to the principles of non-technical skills to ensure that they share the same mental models and have a clear understanding of what is required of themselves and others to complete the tasks safely.

Who may benefit

- Rail operators and all safety-critical workers may benefit from the key lessons of this inquiry.

Factual information Pārongo pono

Narrative

-

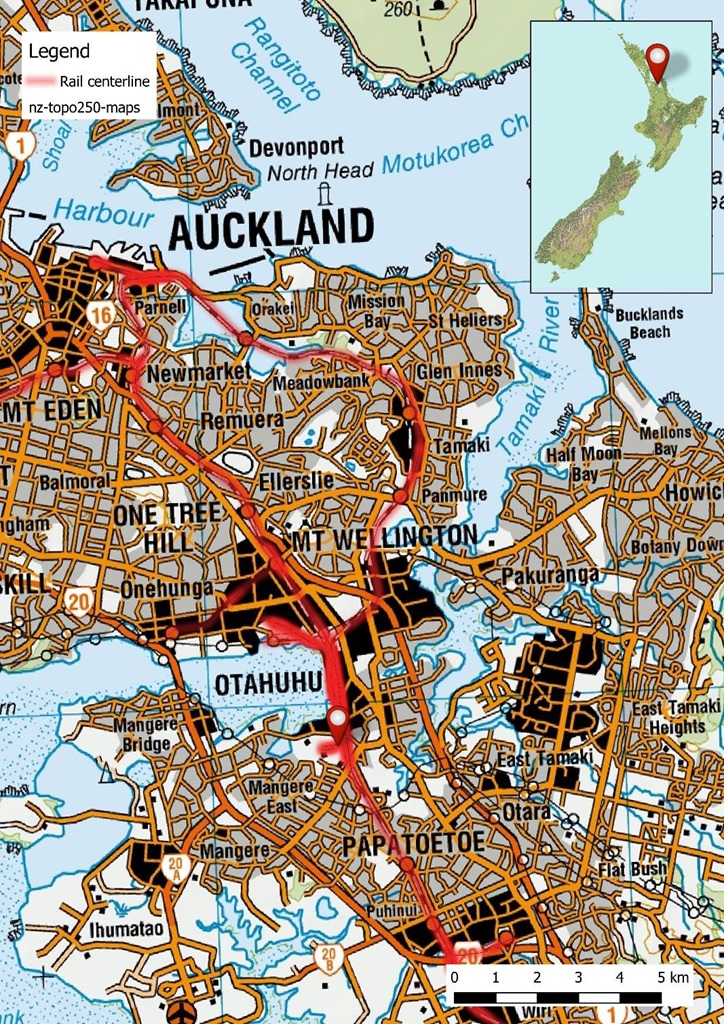

At about 1850 on Sunday 24 March 2019, a KiwiRail work group was operating in a protected work area (PWA) that had been established within a section of KiwiRail’s Westfield yard known as Ōtāhuhu triangle (Figure 2).

-

The PWA had been established at 1000 on 23 March. Its purpose was to protect the work group carrying out repairs to damaged track from a minor derailment. Although the work group was not present, the track had remained closed to rail traffic for Saturday night.

- The repair work was planned to be completed by 1800 on 24 March, but due to delays it was extended by a further hour until 1900.

- The PWA was being managed by a rail protection officer (RPO), who was responsible for ensuring that all personnel within the worksite were protected from rail movements. This was in accordance with KiwiRail’s Rail Operating Rules and Procedures.

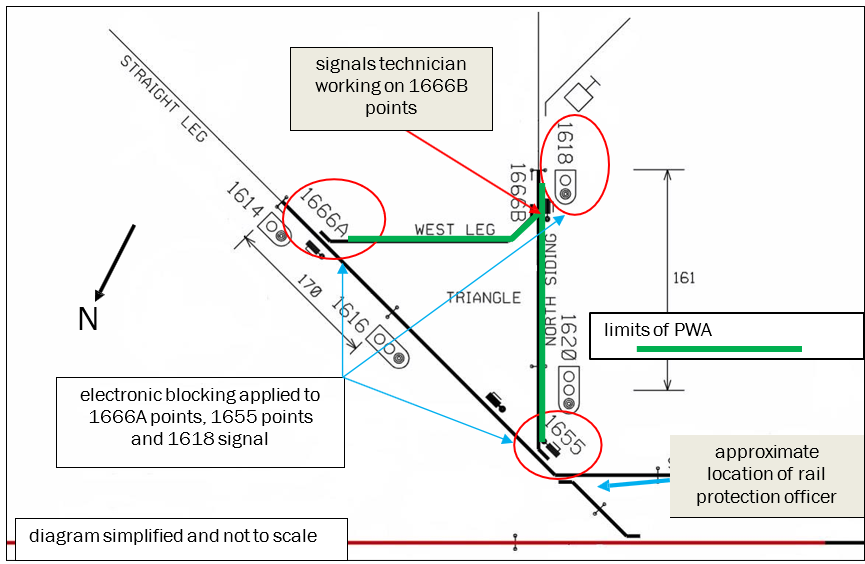

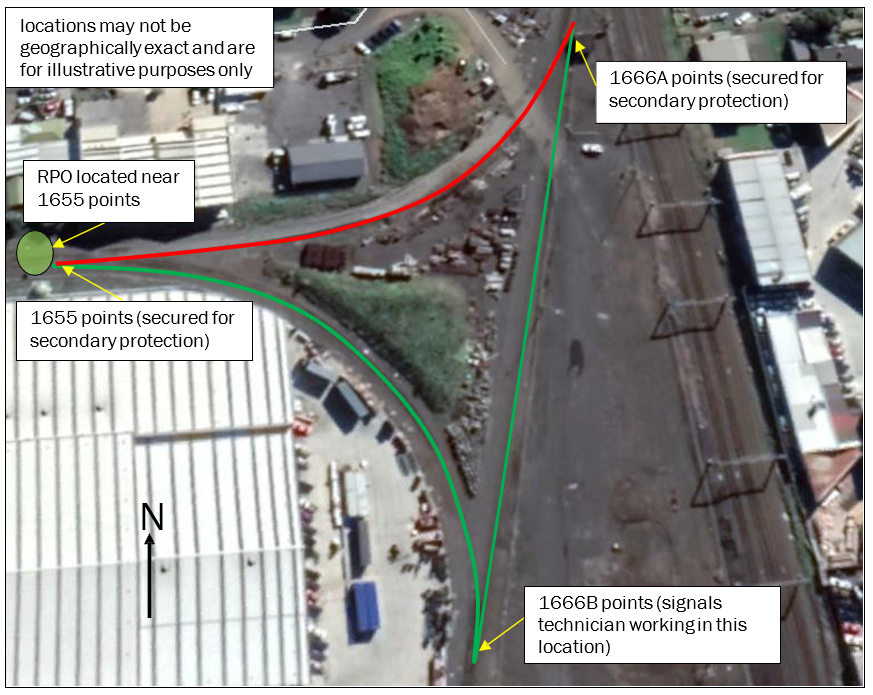

- The RPO was located near 1655 points, in a safe area outside the PWA, so that they could be approached by visitors requiring access to the worksite (Figure 2).

- A signals technician had also been requested to attend the worksite after a work vehicle had reportedly crossed the track within the PWA, and in doing so had possibly caused damage to 1666B points.

- By about 1850 track repairs had been completed and the RPO was in the process of clearing the worksite of all personnel and equipment. This was in preparation for handing the track back to train control for normal operations.

- At this time the RPO was approached by a signals technician who was responsible for the worksite secondary protection (see section 2.24). The RPO and the signals technician briefly discussed the signals technician’s work and the RPO agreed that the signals technician could enter the PWA.

- At 1859 the RPO contacted train control and informed the controller that the worksite was clear of all personnel and equipment and was ready to be handed back. The train controller, who was aware that the secondary protection was still in place, questioned the RPO regarding the status of the signals technician. The RPO advised the train controller that the signals technician was working clear of the track and was not part of the original PWA.

- The train controller again asked for verification that the signals technician was not working on the track. The RPO responded that the signals technician was clear of the track. The train controller accepted this information, but asked the RPO to contact the signals technician and ask them to contact train control.

- The train controller cancelled the track possession authority (the times and limits agreed between train control and the authority holder to take sole occupancy of a section of track) and removed all electronic blocking around the PWA. The track was now available for normal operations, although the two sets of points secured by the signals technician as secondary protection remained inoperable from train control.

- At 1908 the signals technician contacted train control. The train controller queried what was happening with the secondary protection. It became apparent to the train controller that the signals technician was working on the track and was unaware that the RPO had handed the worksite back to train control.

- The train controller then re-established electronic blocking to protect the signals technician for the duration of the work. The train controller also informed the on-duty network control manager of a potential safe-working breach.

- The network control manager reviewed the circumstances of the incident and contacted the RPO by telephone. As a result of the conversation the RPO returned to work and underwent drug and alcohol testing. The test delivered a negative (clear) result.

- There were no rail movements in the area during the period in which the signals technician was working without protection.

- At 1952 the signals technician completed work on the points and contacted train control to confirm that work had been completed and secondary protection removed, and that the electronic blocking was no longer required. Train control removed the electronic blocking and the site returned to normal operations.

Site examination

-

The site was located at the southern end of the Westfield yard. Three tracks consisting of “the straight leg, north siding and the west leg” formed a triangle around a large area of land used for industrial storage (Figure 3).

-

There was no direct line of sight between the RPO and the signals technician due to the curvature of the track.

Figure 3: Satellite view of Ōtāhuhu triangle (Credit: Google Earth modified by the Transport Accident Investigation Commission)

Site protection

- The worksite was protected by utilising KiwiRail’s Rail Operating Rules and Procedures rule 908 –Blocking. There was also a requirement for a secondary protection method, which on this occasion consisted of securing the points away from the PWA.

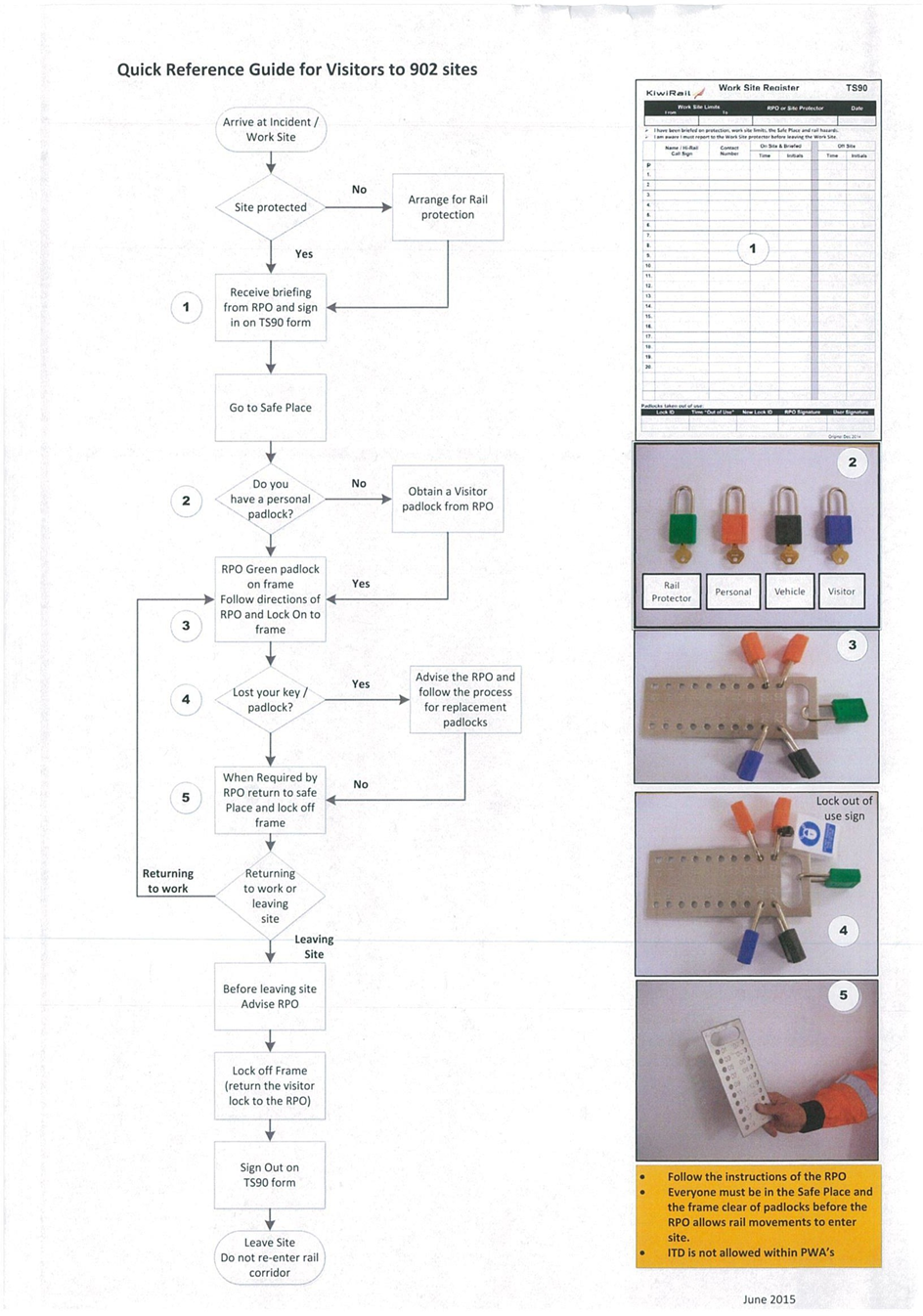

- In addition to the electronic blocking protecting the worksite, the work group itself was working under KiwiRail’s Rail Operating Rules and Procedures rule 902 – Managing a protected work area. Rule 902 dictates that all personnel who need to work within a PWA must contact the RPO to be briefed, signed on to a worksite register and ‘locked on’ (the terminology used to describe someone following the procedure laid down in Appendix 1) using a personal padlock (Appendix 1).

- Rule 902 also stated the limited circumstances in which personnel were excluded from locking on in accordance with normal procedure. The type of work the signals technician was carrying out was not among the limited circumstances.

Electronic blocking and secondary protection

- Electronic blocking was the primary means of protecting the worksite, although secondary protection was also required due to the possibility of rail traffic moving on adjacent tracks.

- The RPO was responsible for communicating with train control to gain possession of the track and establish electronic blocking protection.

- Secondary protection arrangement instructions required that the points allowing entry to the worksite were secured in position by a qualified signals technician. This was to be done in such a manner that traffic was directed away from the worksite and could not be moved inadvertently towards the worksite (Appendix 2).

- The means of securing the points was to de-energise them from a trackside signal equipment panel by removing the fuse to the motor that operated the points.

Key personnel

- The RPO had 18 years’ experience in the role and held all relevant qualifications and a current certification.

- The signals technician had 17 years’ experience in the role and held all relevant qualifications and a current certification.

- The train controller had two years’ experience in the role and held all relevant qualifications and a current certification.

Analysis Tātaritanga

Introduction

- The safe separation and protection of track workers from rail vehicles is a fundamental premise of any rail operation. It is therefore essential that robust and proven safe methods of working are in place to prevent potential interactions between workers and rail traffic.

- On this occasion the RPO allowed a signals technician to enter the PWA without following the procedure prescribed in rule 902 and as a result a significant safety barrier was breached.

- The following analysis discusses the events and circumstances surrounding the cancellation of the PWA before it was handed back to train control, while a worker was still present and working on the track.

Circumstances

- Immediately prior to the incident the work group was in the process of disestablishing the worksite. Members of the work group had been required to work for an additional hour past their rostered time of 1800 to ensure that the track repair work was completed.

- As soon as the worksite was handed back to train control for operational use, the work group members were considered to have completed work for the day and were then free to leave the site.

- However, just as the RPO was preparing to hand the site back to train control they were approached by a signals technician who had been instructed to inspect some trackside equipment. The work being undertaken was within the PWA, some distance away from the RPO’s location and out of line of sight.

The incident

- The RPO reported that during their conversation with the signals technician, the signals technician stated that they needed to examine a set of points, and asked the RPO whether it was necessary to lock on. The lock-on procedure would have allowed the signals technician to inspect the trackside equipment safely. However, this would have also delayed the cancellation of the PWA.

- The RPO reported that they were unaware that the signals technician was inspecting points for potential damage. Instead, they had incorrectly assumed that the work was related to removing the secondary protection in preparation for handing the track back to train control. As a result, the RPO responded that locking on would not be required.

- The RPO reported that when the signals technician requested access they were focused on clearing the work group from the PWA so that the track could be handed back to train control. Although the RPO did not recall feeling any perceived pressure by the additional time already worked by the work group, handing the track back to train control would have allowed the work group to complete their work.

- The signals technician reportedly did not advise the RPO that the work on the points could take some time. The signals technician was also of the view that the PWA could not be handed back to train control while secondary protection, which only the technician could remove, was still in place.

- This series of misunderstandings and procedural lapses allowed the signals technician to commence carrying out work in the rail corridor with a false sense of security. Unknown to the technician, the RPO believed that the technician was working clear of the track and had already advised train control that electronic blocking could be removed. Although the secondary protection was still in place, the removal of the electronic blocking potentially put the signals technician at risk from rail traffic exiting nearby sidings.

Risk controls

- Several non-physical safety barriers were in place to prevent unauthorised access to the PWA. These included:

- the promulgation by KiwiRail of a special bulletin for the work being undertaken, which specified the type of protection required for the duration of that work (Appendix 2). The special bulletin also stipulated the specific rules and conditions under which the work was to take place

- the content of the special bulletin, which was included in the pre-start safety briefing attended by the RPO

- rules and procedures governing work within worksites, which were in place. All personnel involved were trained in these rules and were qualified to work on the track

- primary protection and secondary protection, which were established in accordance with the relevant rules and procedures. The secondary protection (securing of points) was also a physical barrier preventing rail traffic entering the PWA.

- These barriers should have provided adequate safe-working controls. However, their effectiveness was compromised by the non-technical skills employed by the involved personnel.

Non-technical skills

- The Rail Safety and Standards Board of the United Kingdom defines non-technical skills as “the cognitive, social and personal resource skills that complement technical skills and contribute to safe and efficient task performance”. While technical skills describe what you need to do and know for a given safety-critical task, non-technical skills describe how you do that task. The non-technical skill components can be broken down further into sub-categories that include situational awareness, conscientiousness, communication, decision-making and action, co-operation and working with others, workload management and self-management.

- All the key personnel involved in this incident had undergone training in non-technical skills. Nevertheless, the incident highlighted the importance of these skills in creating a safe working environment and ensuring that there are no misunderstandings – particularly skills in communication, possessing a common mental model, challenge and response, and situational awareness.

- Had the signals technician and RPO communicated more effectively regarding the nature and potential implications of the signals technician’s intended work, they would have likely shared the same mental model and understood the consequences of the work requirements. This transfer of knowledge would have also likely improved the RPO’s situational awareness and led to a better understanding of the need to lock on the signals technician.

- There was a missed opportunity for the signals technician to challenge the RPO on the necessity to lock on. The challenge would have also likely led to the RPO gaining a better understanding of and greater clarity on the proposed work. In addition, had the signals technician advised the RPO that the work could take some time, the RPO might have been prompted to decline access to the PWA.

- Had each been better aware of the other’s needs, a simple solution such as the signals technician arranging for their own protection directly through train control was possible. This would then have allowed the work group to complete their work and depart.

- Unfortunately, the challenge made by the train controller to the RPO requesting the whereabouts of the signals technician went unheeded. The RPO’s mental model was that the technician was working clear of the track. This challenge was a further opportunity for the RPO to stop, reassess the environment and regain situational awareness.

- All of the opportunities presented above were instances where a better use of non-technical skills could have minimised the likelihood of the incident occurring.

-

The Transport Accident Investigation Commission (Commission) has raised the issue of non-technical skills in several rail occurrence reports, including in a recommendation to the Chief Executive of the NZ Transport Agency (002/12):

The Commission recommends to the Chief Executive of the NZ Transport Agency that (the agency) require the Executive of the National Rail System Standard to develop standards to ensure that all rail participants meet a consistently high level of crew resource management, and communication that includes the use of standard rail phraseology.

- As a result of this recommendation KiwiRail implemented training programmes that included the principles of non-technical skills. All personnel involved in this incident had been trained to some extent in these principles, but the incident highlighted the importance of continuation training to ensure that these principles remain prominent in the workers’ minds as an important tool in planning for any safe-working scenario.

- On 3 April 2017 the NZ Transport Agency said it was continuing to work with KiwiRail on addressing the recommendation. At the time of publication the recommendation remains open.

- The Commission does not intend to make a further recommendation on this matter.

Other potential factors considered

- Shift-rosters for all personnel were received by the Commission and were compliant with fatigue management standards. Although the work period was extended by one hour, there was no evidence of fatigue having been a factor in the occurrence.

- The RPO undertook a drug and alcohol test soon after the occurrence. There was no indication of drugs or alcohol being a factor.

- All personnel involved had received the respective training and were qualified for the roles they were undertaking at the time of the occurrence.

Findings Ngā kitenga

- It was very likely that a safe-working incident occurred as a result of electronic blocking being removed at the rail protection officer’s request, while the signals technician was still working on the track.

- The rail protection officer’s request to remove electronic blocking was likely due to the rail protection officer and the signals technician not utilising non-technical skills effectively to develop a shared mental model of the work to be undertaken by the signals technician.

Safety issues and remedial actions Ngā take haumanu me ngā mahi whakatika

General

- Safety issues are an output from the Commission’s analysis of factors that have contributed to the occurrence. They typically describe a system problem that has the potential to adversely affect future operations on a wide scale.

- Safety issues may be addressed by safety actions taken by a participant, otherwise the Commission may issue a recommendation to address an issue.

- Recommendations are made to persons or organisations that are considered the most appropriate to address the identified safety issues.

- In the interests of transport safety it is important that safety actions are taken, or any recommendations are implemented, without delay to help prevent similar accidents or incidents occurring in the future.

- No new safety issues or recommendations were identified during the course of this investigation.

Recommendations Ngā tūtohutanga

General

- The Commission may issue, or give notice of, recommendations to any person or organisation that it considers the most appropriate to address the identified safety issues, depending on whether these safety issues are applicable to a single operator only or to the wider transport sector.

- In the interests of transport safety, it is important that recommendations are implemented without delay to help prevent similar accidents or incidents occurring in the future.

New recommendations

- No new recommendations were issued.

Key lessons Ngā akoranga matua

- All personnel undertaking safety-critical roles should adhere to the principles of non-technical skills to ensure that they share the same mental models and have a clear understanding of what is required of themselves and others to complete the tasks safely.

Data summary Whakarāpopoto raraunga

Details

*Times in this report are New Zealand Daylight Savings Times (universal co-ordinated time +13 hours) and are expressed in the 24-hour mode.

Conduct of the inquiry He tikanga rapunga

- On 26 March 2019 the NZ Transport Agency notified the Commission of the occurrence. The Commission subsequently opened an inquiry under section 13(1) of the Transport Accident Investigation Commission Act 1990 and appointed an investigator in charge.

- On 12 April 2019 Commission investigators conducted interviews with the train controller and network control manager.

- On 30 April 2019 Commission investigators conducted a site visit and interviewed the signals technician and the manager of the RPO.

- On 21 May 2019 Commission investigators conducted an interview with the RPO.

- The Commission obtained the following documents and records:

- the signalling and interlocking diagram for Ōtāhuhu triangle

- train control diagrams relevant to the occurrence

- copies of incident reports completed by personnel involved in the occurrence

- witness statements and interviews

- the training records for involved parties

- work rosters for the involved parties covering the lead-up to the occurrence

- copies of the special bulletin promulgated by KiwiRail relevant to the occurrence

- rules and regulations pertaining to PWAs

- recordings of calls to and from train control relevant to the occurrence

- copies of forms completed by the RPO during the establishment of the PWA.

- On 2 December 2019 the Commission approved a draft report for circulation to five interested persons for their comment.

- Five submissions were received. The Commission considered the submissions, and no changes were required to the final report.

- On 3 April 2020 the Commission approved the final report for publication.

Glossary Kuputaka

- Electronic blocking

- Electronic blocking is a method of protection whereby the train controller uses the train control system to prevent signals held at red (stop) being placed at green or yellow (proceed). Having to stop for red signals prevents rail traffic from entering a section of track that has been blocked.

- Points

- Points can be in either ‘Reverse’ or ‘Normal’. Reverse is the position of points set for a less commonly used route. Normal is the position of points set for a more commonly used route, usually straight running.

- Protected work area

- A section of line or lines where rail personnel are carrying out activities using an approved protection method

- Secondary protection

- An additional protection method, used in multi-worksite protected work areas.

- Train control

- The centre from where the movement of all rail vehicles and track access in a specified area are brought under the direction of a Train Controller

Appendix 1. KiwiRail guide to rule 902

Appendix 2. Special bulletin 313