On 26 February 2025, the Commission recommended that the director of Maritime New Zealand:

6.4.1 Adjust the level of oversight and monitoring of the survey system to ensure it is sufficient to give MNZ confidence that the system is fit for purpose, providing for the safety of the vessel and its occupants. [005/25]

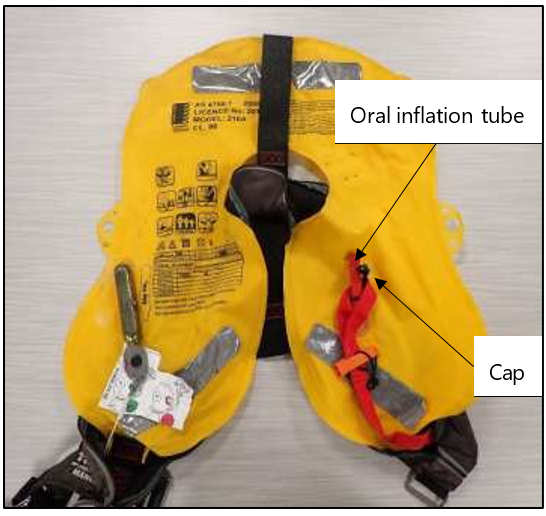

6.4.2 Work with lifejacket industry stakeholders and commercial operators to identify and implement effective safety measures that mitigate the risks associated with incorrectly re-arming and re-packing inflatable life jackets. [006/25]

6.4.3 Implement a requirement for Recognised Surveyors to record in their survey report the servicing and expiry details for life-saving appliances onboard the vessel, to reduce the risk of appliances that are not fit for purpose remaining in service. [007/25]

6.4.4 Work with lifejacket industry stakeholders to educate and raise awareness with users of inflatable lifejackets of the:

6.4.5 Work with lifejacket industry stakeholders and commercial operators to identify and implement appropriate safety measures that mitigate the potential risks associated with:

-

inflating a lifejacket while obstructed overhead or in a confined space, limiting a wearer’s ability to escape to a safer area

-

the lack of guidance and procedures relating to the doffing and deflation of inflatable lifejackets, to increase a wearer’s ability to remove an inflated lifejacket if needed. [009/25]

6.4.6 Work with lifejacket industry stakeholders to develop guidelines on the information that should be covered in safety briefings on lifejacket use, including doffing, deflation and hazards. [010/25]

6.4.7 Support the submission of papers to the IMO through an appropriate IMO forum for their consideration to raise awareness about the importance of:

6.4.8 Introduce a requirement for crew of passenger vessels equipped with Category II EPIRB’s to also carry a personal location beacon or similar device capable of transmitting a distress message, to increase the timeliness of notification of an emergency. [012/25]

On 21 March 2025, Maritime New Zealand replied:

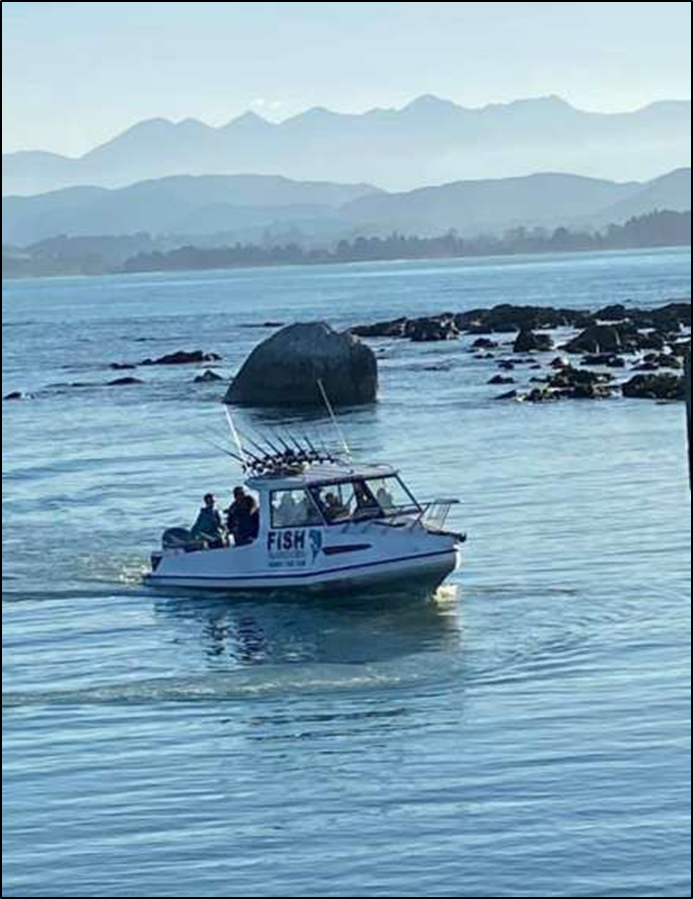

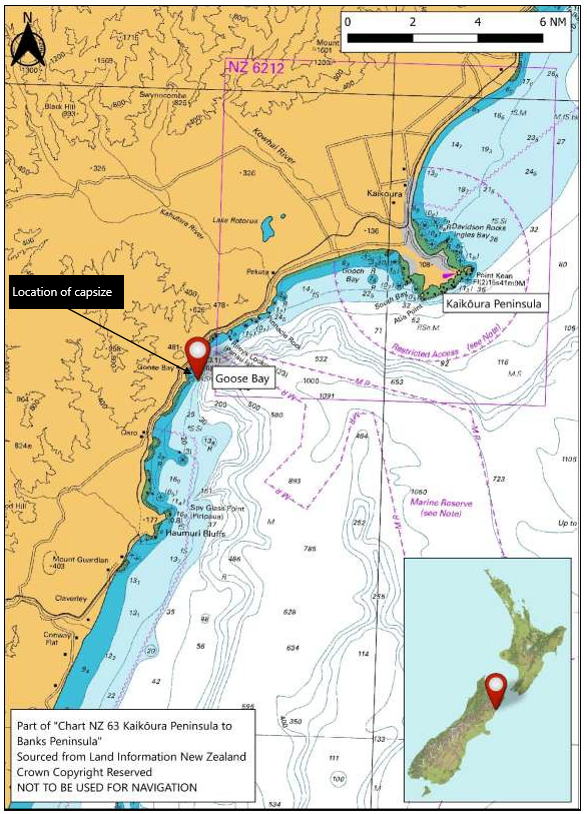

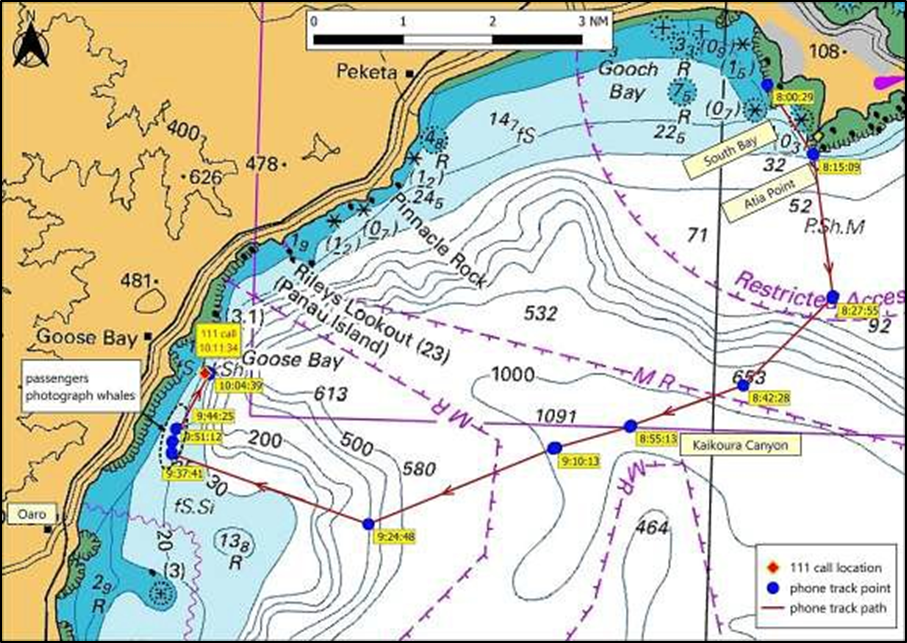

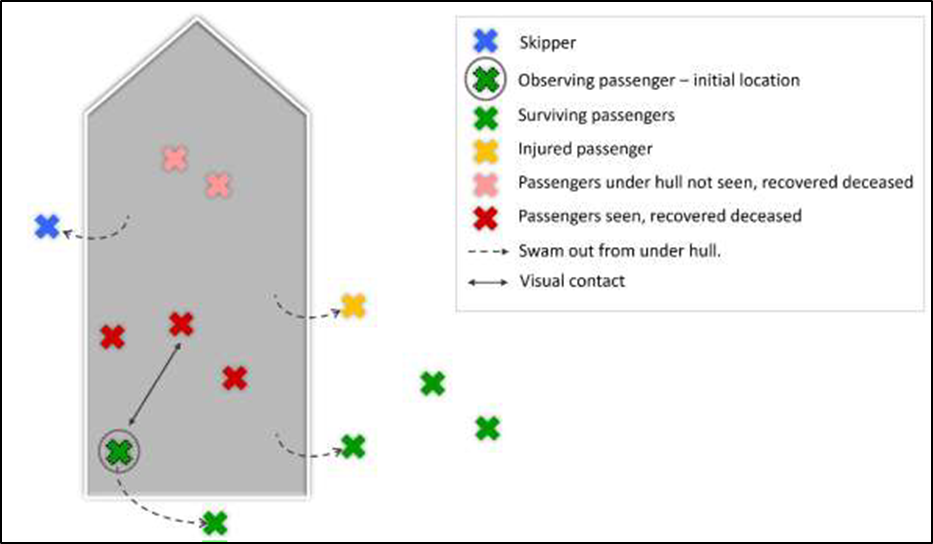

I write in response to your letter from 11 March 2025 advising Maritime New Zealand (Maritime NZ) of final recommendations 005/25 – 012/25 in regards to MO 2022-206, capsize of Charter fishing vessel i-Catcher, Goose Bay, New Zealand.

The i-Catcher incident was a tragic event resulting in the loss of 5 lives. As usual with TAIC reports, we welcome the insights gained.

We note that the following recommendations to Maritime NZ:

Recommendation 005/25

Adjust the level of oversight and monitoring of the survey system to ensure it is sufficient to give MNZ confidence that the system is fit for purpose, providing for the safety of the vessel and its occupants.

This recommendation has been accepted and is being implemented.

Maritime NZ has been actively strengthening our third-party oversight since 2017 through a more consistent and systemic approach which involves the following actions:

An established entry control process for surveyors with initial and renewal assessments prior to a certificate of recognition being issued.

Reactive reviews of survey reports take place in response to issues or as part of certificate applications.

A range of guidance material exists such as the Survey Performance Requirements

Technical support is available for surveyors raising issues

Maritime NZ provide an annual surveyor seminar covering issues and changes to policies.

Our additional funding, secured through the funding review has resulted in three new staff being recruited, who now form the core of a dedicated Third Party Oversight team. The team has a specific leadership role, accountabilities and responsibilities in relation to Third Party oversight. It is taking an overall system approach to oversight ensuring that the development of appropriate standards and guidance, alongside the design of approaches to monitor surveyor performance. A multi-year programme of work is under development and we anticipate that surveyors to be highly prioritised.

Recommendation 006/25

Work with lifejacket industry stakeholders and commercial operators to identify and implement effective safety measures that mitigate the risks associated with incorrectly re- arming and re-packing inflatable life jackets.

This recommendation is under consideration.

Maritime NZ intends to engage with manufacturers and the sector, both commercial operators and recreational craft users, to determine the scale of the issue around re-arming and re-packing, and what further work might be required around any interventions needed.

An optimal outcome would be aligned industry and provider support for the types of changes that will make key differences to safe PFD use.

In addition, Maritime NZ has recently published this related guidance: Servicing and testing of life-saving appliances - Maritime NZ

Recommendation 007/25

Implement a requirement for Recognised Surveyors to record in their survey report the servicing and expiry details for life-saving appliances onboard the vessel, to reduce the risk of appliances that are not fit for purpose remaining in service.

This recommendation has been partially accepted.

Maritime NZ considers that the primary responsibility to ensure the periodic service of inflatable lifejackets is correctly placed on the owner and master as outlined in Maritime Rule 42A.38.

Currently Maritime NZ provides a range of resources to surveyors, including a survey report template setting out the types of matters to consider for different aspects of the vessel. The template indicates that surveyors inspect the service records of a range of safety equipment, including inflatable lifejackets.

Additionally, Maritime NZ has recently published this related investigation insight:

Servicing and maintenance of lifejackets - Maritime NZ

Maritime NZ will consider this recommendation as part of the survey component of the 40 Series reform work, which is in progress, as this work looks at monitoring service requirements.

Recommendation 008/25, 009/25 and 010/25

008/25 - Work with lifejacket industry stakeholders to educate and raise awareness with users of inflatable lifejackets of the:

doffing and deflation procedures

potential hazard of inflating when obstructed overhead.

009/25 - Work with lifejacket industry stakeholders and commercial operators to identify and implement appropriate safety measures that mitigate the potential risks associated with:

inflating a lifejacket while obstructed overhead or in a confined space, limiting a wearer's ability to escape to a safer area

the lack of guidance and procedures relating to the doffing and deflation of inflatable lifejackets, to increase a wearer's ability to remove an inflated lifejacket if needed.

010/25 - Work with lifejacket industry stakeholders to develop guidelines on the information that should be covered in safety briefings on lifejacket use, including doffing, deflation and hazards.

Recommendations 008/25,009/25 and 010/25 are under consideration.

Maritime NZ will consider these recommendations as part of the work programme for our relevant harm prevention programmes. This is a complex and difficult issue and may require a mix of responses to gain the optimal outcome. Maritime NZ will, through engagement with the relevant key stakeholders determine what the most appropriate approaches will be.

Recommendation 011/25

Support the submission of papers to the IMO through an appropriate IMO forum for their consideration to raise awareness about the importance of:

doffing and deflation procedures

the potential hazard of inflating when obstructed overhead. This recommendation is accepted and being implemented.

Maritime NZ has supported TAIC by drafting, on request, a paper to inform the international community of lessons learned from the incident. The paper is due to be submitted to the 11th session of the Sub-Committee on Implementation of IMO Instruments (III 11) in July 2025. The paper is currently being internally reviewed at Maritime NZ before review by TAIC.

Recommendation 012/25

Introduce a requirement for crew of passenger vessels equipped with Category II EPIRB’s to also carry a personal location beacon or similar device capable of transmitting a distress message, to increase the timeliness of notification of an emergency.

This recommendation has been partially accepted.

Maritime NZ notes the potential value and benefit to rescue operations. Consideration of the merits will be included in ongoing regulatory reform work.

Maritime NZ has already reviewed capsize incidents in New Zealand waters. Our analysis indicates that small passenger vessels operating within inshore limits present the most risk in a capsize event. We are considering rules changes that would require the master of these vessels to carry a means of communication.

Maritime NZ will be seeking public submission in these proposals as part of the Series 40 reform work.