On 27 April 2022, the Minister of Transport directed the Transport Accident Investigation Commission to investigate two fatal stevedoring accidents under section 13(2) of the Transport Accident Investigation Commission Act 1990. Although the accidents occurred separately, the Commission identified common systemic safety issues and has therefore presented both inquiries in a single report, noting their relevance to the wider stevedoring industry. The first accident occurred on 19 April 2022 at the Port of Auckland, where a stevedore employed by Wallace Investments Limited was fatally crushed after moving beneath a suspended container onboard the Capitaine Tasman. The second occurred on 25 April 2022 at Lyttelton Port, where a stevedore employed by Lyttelton Port Company Limited was found deceased on the ETG Aquarius, buried under coal during loading operations.

Executive summary Tuhinga whakarāpopoto

What happened

- On 27 April 2022, the Minister of Transport directed the Transport Accident Investigation Commission to open two inquiries under section 13(2) of the Transport Accident Investigation Commission Act 1990. The inquiries were in response to two fatal stevedoring accidents that occurred at two New Zealand ports.

- Separate investigations were conducted into each accident. There were common systemic safety issues identified in the two accidents and the Commission has therefore published the two inquiries in a single report. These systemic issues are relevant to the wider stevedoring industry.

- The first accident occurred on 19 April 2022 at the Port of Auckland. A stevedore, working onboard the container vessel Capitaine Tasman, moved underneath a suspended 40-foot container and suffered crush injuries as a result of the container being lowered onto them. The stevedore was employed by Wallace Investments Limited (WIL), an independent stevedoring company operating at the Port of Auckland.

- The second accident occurred at Lyttelton Port on 25 April 2022. A stevedore, involved in the process of loading coal onto the bulk carrier ETG Aquarius, was discovered, deceased, on the deck of the vessel, buried under a quantity of coal. The stevedore was employed by the Lyttelton Port Company Limited (LPC).

Why it happened

- The Commission found that both WIL and LPC were in the process of improving their respective safety systems. However, at the time of the accidents there were deficiencies common to both organisations. The risks associated with work activity were primarily managed with administrative risk controls, yet robust safety assurance processes to ensure that these controls remained effective were lacking. As a result, neither LPC nor WIL adequately understood how the day-to-day behaviour of their employees was negating the effectiveness of already vulnerable control measures.

- While both organisations were attempting to improve their safety management systems, a lack of cohesiveness within the stevedoring community meant there was little ability to benchmark comprehensively with others in the industry. With no best practice guidelines, no minimum training requirements and few safety-related information-sharing platforms, leadership from within the sector was found lacking.

- Historically, stevedoring has a poor safety record (International Labour Office, 2018), yet it is not regulated with the degree of rigour afforded to other high-risk industries. From a regulatory perspective, neither organisation received a satisfactory level of proactive oversight of their stevedoring operations. Most regulatory interactions were limited to LPC and WIL reporting notifiable events under the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015, and to any subsequent follow-up by Maritime New Zealand (MNZ) and WorkSafe New Zealand (WorkSafe) as a result of those notifications. Reactionary reporting and associated regulatory sanctions provide little insight into the health of an organisation’s safety system or assurance of future safety performance. Nor do they encourage information sharing within the industry to encourage safety growth across the sector.

- The Commission has made five safety recommendations as a result of these two inquiries.

What we can learn

- Those who work in high-risk industries are not necessarily exposed to adverse events on a regular basis. This can lead to a desensitisation to risk, which itself becomes a hazard.

- When risk is not fully understood or appreciated, a variety of factors can lead to employees taking shortcuts or drifting away from rules (see footnote 16 for explanation of human behaviour within organisations). Passive safety messages and reminding people to follow procedures are not effective means by which to change risk perceptions or modify behaviours.

- The way in which tasks are designed and procedures are written is often incongruent with how day-to-day work activity is conducted. A critical component of any safety system is the ability to identify, understand and resolve the reasons for the disparity.

- Where administrative risk controls are necessary to manage hazards associated with high-risk activity, appropriate supervision and a culture of strong safety leadership is required to ensure their effectiveness.

- Industry collaboration and benchmarking is one of the most effective ways to improve safety standards and support continuous improvement.

- Reactive interventions are not a substitute for proactive regulatory oversight of high-risk industries, particularly those with a poor safety record.

Who may benefit

- Regulatory bodies, port organisations, stevedoring organisations, stevedores, vessel operators, anyone designing safety standards, and anyone working in a high-risk industry may benefit from this report and the Commission’s recommendations.

Factual information Pārongo pono

- On 27 April 2022, the Minister of Transport directed the Commission to open two inquiries under section 13(2) of the Transport Accident Investigation Act 1990. The inquiries were in response to two fatal stevedoring accidents that occurred at New Zealand ports. The first accident occurred at the Port of Auckland on 19 April 2022, when a stevedore employed by Wallace Investments Limited (WIL) was crushed by a container during loading operations onboard the Capitaine Tasman. The second accident occurred at Lyttelton Port on 25 April 2022, when a stevedore employed by Lyttelton Port Company Limited (LPC) was buried under a quantity of coal onboard the ETG Aquarius.

- During its two inquiries, the Commission identified commonalities between the two accidents, including several systemic safety issues that are relevant to the wider stevedoring industry. For this reason, the two investigations have been published within a single report.

- This section of the report sets out the context for the investigations, specifically an overview of the stevedoring industry within New Zealand. This includes the hazards associated with stevedoring activities and the importance of having an effective safety management system (SMS). Commonalities between the two accidents are also noted. Section 3 discusses the wider safety issues the Commission identified for the New Zealand stevedoring industry. Section 4 outlines the safety actions that have been taken since the two accidents. Section 5 contains the Commission’s recommendations arising from its two inquiries.

- Appendix A of this report covers the investigation into the accident at the Port of Auckland, MO-2022-203. Appendix B covers the investigation into the accident at Lyttelton Port, MO-2022-202.

Introduction to port operations

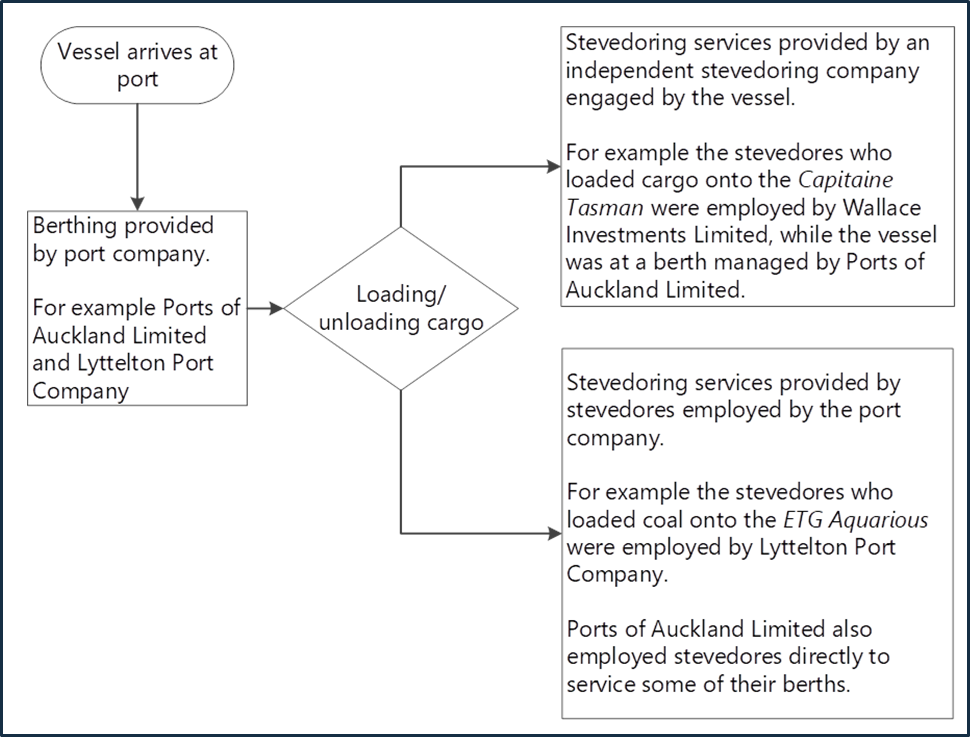

- A port is a location where goods are loaded and unloaded from ships. The two locations where these accidents took place are the Port of Auckland and Lyttelton Port (see Figure 3). Port companies, such as Ports of Auckland Limited (POAL) and Lyttelton Port Company Limited (LPC), operate and manage the infrastructure and facilities at these ports, such as berthing ships, loading and unloading cargo, and providing storage and transportation.

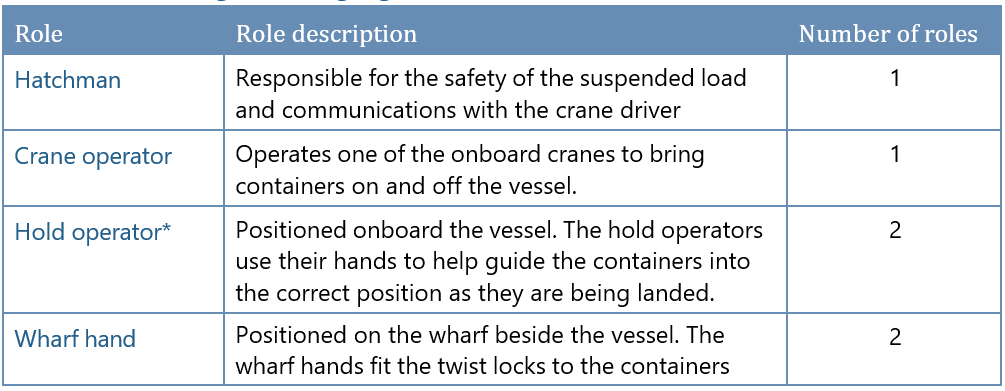

- Stevedoring activity includes loading and unloading of the cargo carried on vessels, stacking and storing cargo on the wharf, and receiving and delivering cargo within the terminal or port facility. Stevedores may be employed directly by the port company, or by a privately owned stevedoring company that is independent of the port company (see Figure 4). Stevedores usually operate in teams, known as gangs. Often, several gangs will be supervised by a foreman. The stevedoring roles within the gangs involved in these two accidents are described in the factual information for each inquiry (see Appendices A and B).

- Shipping companies operate the ships that transport the cargo. Depending on their needs, they can use stevedores from the port company or stevedores from an independent stevedoring company to handle the loading and unloading of cargo at port.

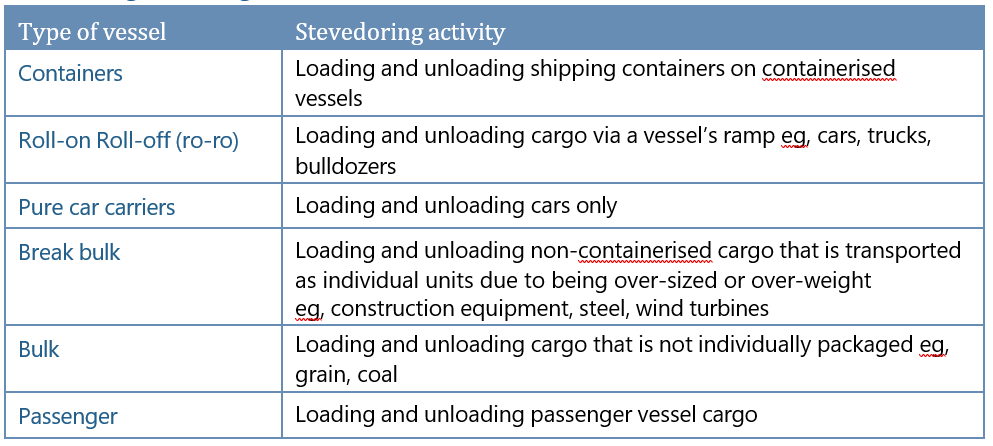

- Stevedores undertake various types of cargo handling (see Table 1):

Regulation of stevedoring in New Zealand

- The Waterfront Industry Act 1953 (WIA) was passed in New Zealand to regulate the operations and conditions of the country's waterfront industry. The WIA was intended to protect the rights of workers and employers in the industry and focused on the efficiency and costs of operations on the waterfront.

- The WIA established the Waterfront Industry Tribunal (judicial functions) and the Waterfront Industry Commission (administrative functions).

- However, it was not until the WIA was reconsolidated and amended in 1976 that the Tribunal and Commission could explicitly consider the safety of the waterfront industry (the Waterfront Industry Act 1976 is sometimes referred to as the Waterfront Industry Commission Act 1976).

- Throughout the 1970s and 1980s several legislative changes ultimately saw the dissolution of both the Tribunal and Commission (the Waterfront Industry Commission Amendment Act 1987 dissolved the Tribunal, and the Waterfront Industry Reform Act 1989 dissolved the Commission).

- These amendments meant that:

- ports were required to employ their own workforces and function under the Labour Relations Act 1987 in the same manner as any other employer

- the common standard of stevedoring labour administration and regulation was removed.

- These changes effectively resulted in deregulation of the stevedoring workforce, and individual ports and shipping agencies became free to set their own rates and practices for the services they provided.

- It was not until the early 1990s that stevedoring attracted safety regulation again, with health and safety on ports falling under the Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992 (HSE) (administered and enforced by the Department of Labour) and on vessels, falling under the Maritime Transport Act 1994 (MTA) (administered and enforced by the Maritime Safety Authority (MSA), which was renamed Maritime New Zealand (MNZ) in July 2005).

- In 2002, safety for work onboard vessels was moved from the MTA into the HSE. At the same time, a provision for designation was also introduced that allowed the Prime Minister to designate an agency to be the health and safety regulator for an industry, sector or type of work.

- In 2003, MSA was given a designation and new appropriation for activity associated with health and safety regulation onboard vessels. Operational agreements to support the designation were developed between the Department of Labour and MSA.

- In 2015, the HSE was repealed and replaced by the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 (HSWA), administered by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE). WorkSafe New Zealand (WorkSafe) was established as the primary regulator for New Zealand’s workplace health and safety, with MNZ retaining their designated role for health and safety onboard vessels.

- HSWA places the responsibility for securing the health and safety of workers and workplaces on the person conducting a business or undertaking (referred to as a PCBU). Port companies and stevedoring companies are PCBUs under HSWA, as are operators of New Zealand-flagged vessels. HSWA does not generally apply to foreign-flagged vessels operating in New Zealand waters. However, it does apply when stevedoring companies are undertaking work onboard foreign-flagged vessels at a New Zealand port.

- Given the designation held by MNZ, in a port environment there are two regulators: WorkSafe is the regulator for any shore-based operations and MNZ is the regulator for operations onboard the vessel. The boundaries between shore-based and vessel-based operations can be ambiguous, for example when a vessel’s crane is being used to lift cargo from the wharf onto the vessel.

- To facilitate cooperation, the two regulators agreed a memorandum of understanding in 2018. Where jurisdictions or interests overlap, joint work programmes are undertaken. If an incident occurs and it is initially unclear who has jurisdiction, both WorkSafe and MNZ will attend.

- HSWA has 16 pieces of secondary legislation that further define the responsibilities of PCBUs, including those that might apply to specified persons or circumstances. One of those is the Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations 2016 (HSWA-GRWM), which prescribe a risk management process for certain working conditions. Those working conditions include raised and falling objects and substances hazardous to health – both of which are inherent in some stevedoring activities.

- HSWA-GRWM requires PCBUs, so far as it applies to specific hazards and/or risks as prescribed in regulation, to identify hazards that could give rise to reasonably foreseeable risks, manage them using a hierarchy of control measures, maintain effective control measures, and review and revise control measures to make sure they are effective (see the Managing the risk of harm in stevedoring operations subsection below). The regulations also require the PCBU to ensure that the supervision and training provided to a worker is suitable and adequate. Exactly how the PCBU complies with the regulations is left to the discretion of the PCBU.

- HSWA duties for managing health and safety risks will overlap in shared workspaces such as a port, or when services are being contracted or sub-contracted, such as when a shipping company requires the use of stevedoring services at a port. Organisations are not expected to operate in isolation and HSWA requires that PCBUs must, as far as is reasonably practicable, consult, cooperate and coordinate activities with all other PCBUs with whom they share overlapping duties (HSWA, s 34(1)). Which PCBU is best placed to manage a particular risk depends upon the degree of influence and control the PCBU has in the circumstances. For example, if stevedores are working on a vessel, the stevedoring company may be best placed to manage the worksite itself, but the shipping company would likely have a duty to ensure that equipment such as the vessel’s cranes were maintained to the required standard and were safe to operate.

- Beyond the responsibilities required of a PCBU, there are no additional or specific requirements for stevedoring activity within HSWA. This was also the case under the previous HSE.

- Since the regulation of safety for work onboard vessels was removed from the MTA in 2002, the MTA has no regulations specific to stevedoring organisations. However, there are several rules relating to port activities that are relevant to stevedoring activity.

- The MTA lays out the responsibilities of port operators for maritime safety, including that port operators must not allow the port to be operated in a manner that causes unnecessary danger or risk to vessels, or people and property on vessels.

- There are no existing Maritime Rules specifically regulating stevedores or stevedoring, although some parts contain provisions that apply to stevedoring.

- Regulatory requirements regarding training for stevedoring activity do not extend beyond the primary duty of care laid out in HSWA, to provide information, training, instruction or supervision that is necessary to protect all people from risks to their health and safety arising from work.

- Non-compulsory qualifications for stevedoring exist within the NZQA framework. The New Zealand Certificate in Port Operations offers three options of study: port administration, cargo handling, and heavy machinery.

Managing the risk of harm in stevedoring operations

- Globally, the modernisation of stevedoring has seen increasingly sophisticated technology within port environments. The introduction of containerised shipping and roll-on roll-off (ro-ro) vessels in the 1960s marked a significant change in cargo-handling, which had until then largely remained unchanged. While many of these developments have reduced the level of human-intensive operations, there has not been a comparative reduction in injury risk (Fabiano et al., 2010). Historically, port work had a poor safety record and it is still regarded as an occupation with very high accident rates (Ronza et al., 2005; International Labour Office, 2018). International data from 2022 shows that approximately 34 per cent of incidents involving vessels occurred when docked in port (Rightship, 2023) (where report data identified location).

- Domestically, there have been 18 deaths amongst port workers since 2012. A recent examination of port safety within New Zealand (Port Health and Safety Leadership Group, 2022) shows that the number of fatalities across a 10-year period has remained consistent, averaging 1.8 deaths per annum. As a proportion of the workforce, stevedore fatalities occur at a rate of approximately 20 deaths per 100,000 workers, which is the second highest rate of any sector within New Zealand.

- When compared internationally, New Zealand ports do not move high volumes of cargo (Lloyds List One Hundred Ports, 2022). For example, in terms of container movements per year, most New Zealand ports would be considered ‘small’ (less than 0.5 million TEUs (Twenty-foot Equivalent Units) per year, as defined by Container Port Performance Index 2021). However, New Zealand’s port-worker fatality rate is higher than other countries that move significantly more cargo, such as the United States. In terms of the number of deaths, considering the amount of cargo moved, New Zealand’s fatality rate is two- to three-times higher than both the UK and Hong Kong. The fatality rate for New Zealand stevedores is comparable to Australia, despite the amount of cargo handled being considerably less.

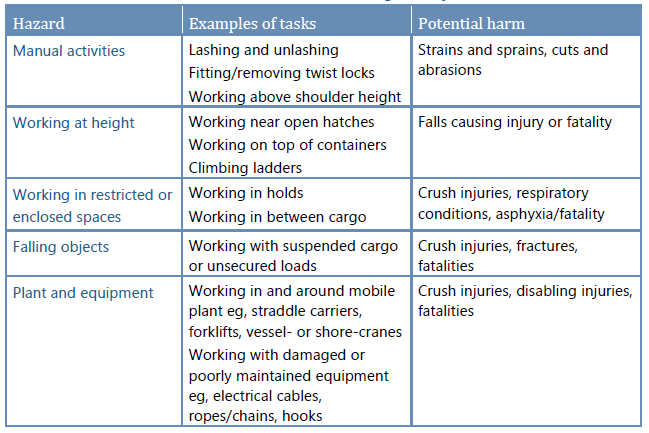

- Falls from height and crushing by machinery or vehicles were the two most common causes of fatalities within New Zealand ports, followed by vehicle crashes and being hit or crushed by cargo.

- The Port Sector Insights Picture and Action Plan (Port Health and Safety Leadership Group, 2022) reported that there were 397 reported notifiable injuries at New Zealand ports between 2012 and 2022, the most common causes being slips, trips and falls, followed by workers being caught between objects. Information provided by sector participants and analysed as part of this work (see paragraphs 4.9 to 4.12 of this report for further information on the Port Sector Insights Picture and Action Plan) suggests a correlation between increasing volumes of cargo and rising rates of harm. In the previous five to six years, MNZ has conducted 39 investigations into PCBUs that were undertaking stevedoring activity at New Zealand ports. Four investigations resulted in prosecution. MNZ also issued five prohibition notices and 19 improvement notices.

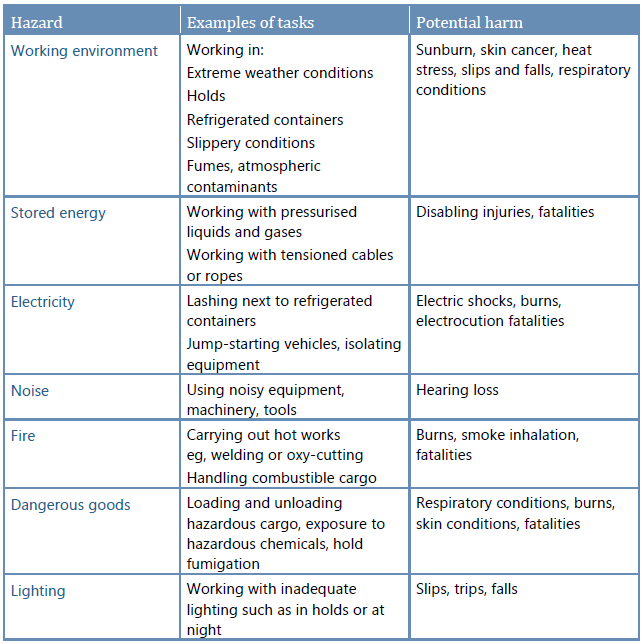

- Hazard refers to anything that has the potential to cause harm. Some activities have an inherently high risk of causing harm because of the nature of the hazards that are associated with the activity. Stevedoring fits into this category because it puts workers near heavy machinery, significant stored energy hazards and dangerous materials, often whilst working at heights (see Table 2).

- Risk management refers to the systematic process of hazard identification, risk assessment and treatment of the risk using risk controls. Risk controls are mechanisms designed to either eliminate, mitigate or reduce to as low as reasonably possible, the unwanted outcomes posed by exposure to hazards.

- Risk controls can be classified according to where on the potential hazard-to-risk trajectory they are employed. Preventative risk controls are put in place to prevent the risk associated with the hazard from occurring. For example, a guard cover over a switch to prevent inadvertent selection of the switch is a preventative risk control. Recovery risk controls are designed to reduce the consequences of the negative outcome should the risk associated with the hazard eventuate. The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) is a common recovery risk control, such as a harness protecting a worker from injury should a fall from height occur.

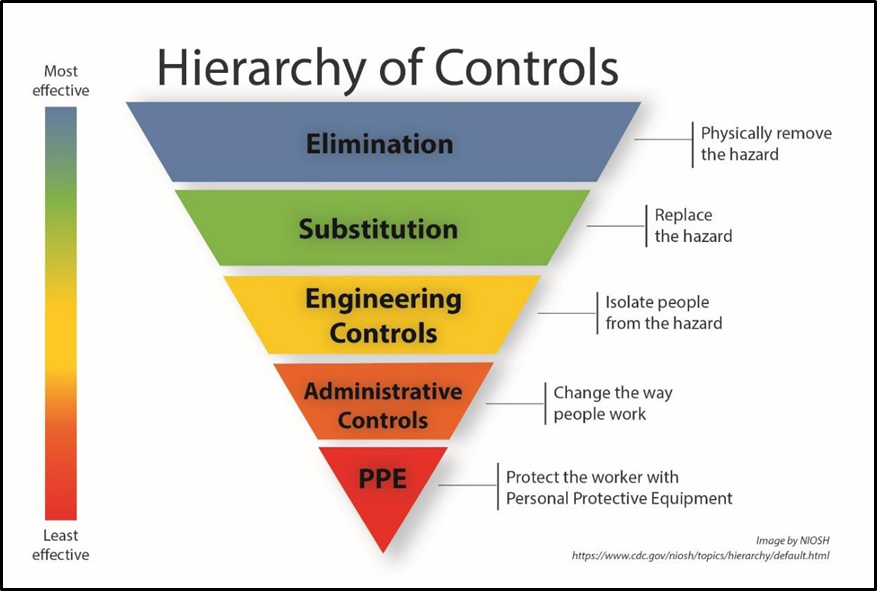

- There are multiple ways to control risk and the mechanisms to do so can be grouped depending on their level of effectiveness. This is commonly known as the hierarchy of controls (see Figure 5).

- The most effective way to manage a risk is to eliminate its source by removing the hazard altogether; if the hazard does not exist, no risk is posed. If it is not possible to remove the hazard, then the next most efficient control is reduction of any potential risk. This can be achieved in several different ways; however, some methods are more effective than others.

- Firstly, substitution of the hazard should be considered. This involves replacing the hazard source with something that creates less risk. If this is not reasonably practicable, an engineering control will provide the best defence. Engineering controls are physical in nature and can be designed into a system to protect an individual from the hazard. Guard switches and protective barriers are examples of engineering controls where there is some degree of isolation between the worker and the hazard.

- Less effective than engineering controls are administrative risk controls. These consist of measures such as providing workers with information about the hazard through training and having documented procedures or work instructions in place. Safety messaging is an example of an administrative control. Finally, PPE should be used to protect against any remaining risk.

- HSWA-GRWM requires PCBUs to implement risk control measures, so far as they apply to certain working conditions, in accordance with this hierarchy of controls. If it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate a risk (HSWA-GRWM, r 6(1)), then PCBUs must, so far as reasonably practicable, use substitution, isolation or engineering controls in the first instance (HSWA-GRWM, r 6(3)) followed then by the less effective administrative risk controls and PPE (HSWA-GRWM, rr 6(4) and 6(5)).

- Once risk controls have been established, they must be reviewed and, as necessary, revised to ensure that their effectiveness is maintained (HSWA-GRWM, rr 7 and 8).

Effectiveness of administrative risk controls

- Currently, many of the inherent hazards in stevedoring activities are managed with administrative risk controls. While technological innovation has increased the engineering solutions, most stevedoring operations remain human-centric. As of 2021, there were only 53 container terminals (ports of Auckland’s Ferguson Terminal has since reverted to manual saddle cranes) around the world that utilised some degree of automation, which represents 4 per cent of the total global container terminal capacity (International Transport Forum, 2021). Moreover, while some stevedoring activities could be automated, some of the most dangerous aspects of container handling (such as lashing, and fitting twist locks) are considered more problematic in terms of automation (International Transport Forum, 2021). The degree to which automation will increase port-workers’ health and safety is still uncertain and, with the ability to fully automate ports still some time away, the requirement for stevedores to work in hazardous environments remains. (The argument that increased automation will rapidly lead to a reduction in harm by reducing human involvement in the system, is not straightforward. Automated processes still require supervision and appropriate management. Within the port environment, there is currently little empirical data to support the assumption that the health and safety of container terminal workers has improved in the ports that have introduced automated processes. Several automated ports have had accidents with equipment, including the Ports of Auckland’s Freyberg Terminal, which experienced two separate incidents involving automatic straddle cranes. See International Transport Forum (2021)).

- The primary reason that administrative risk controls are not as effective as other types of risk control is that they rely heavily on compliance. For administrative risk controls to work, employees must always follow instructions, never make mistakes and never put themselves in harm’s way – a concept that is at odds with human behavioural science. (In addition to being susceptible to human error, people rarely always follow rules or instructions precisely. Individuals tend to drift away from rules and procedures as they gain familiarity with the tasks they are performing. While policies and procedures are prescribed to set boundaries for safe operations, workers may experiment with these boundaries to become more productive or obtain some benefit. This experimentation can lead to adaptations of procedures and a shift beyond the prescribed boundaries toward unsafe practices. Without intervention, this can lead to other employees observing what appears to be a successful adaptation of procedures and a spread of such behaviour takes place throughout the workforce. In the absence of any negative repercussions such adaptations are unlikely to be recognised as deviations as often these behaviours result in successful outcomes. Over time, adaptation of procedures slowly becomes the normal behaviour and any risk associated with short-cuts or workarounds is unlikely to be recognised. This is commonly described as ‘normalisation of deviance’, a phrase first used when examining the 1986 Challenger disaster (see Vaughan, (1996)). For an overview of normalisation of deviance in high-risk industries, see Sedlar et al. (2023)).

- There are multiple organisational factors that influence employees and can contribute to engaging in at-risk behaviour. At-risk behaviour is a term used to describe behavioural choices that increase risk, specifically where the risk is not recognised or is mistakenly believed to be justified (Marx, 2009). Common motivators (factors that can encourage people to break rules or not follow procedures (Santiago, 2007)) of at-risk behaviour within organisations are:

- financial gain

- saving time/making life easier

- impractical safety procedures

- unrealistic operating instructions

- unrealistic operating schedules

- demonstrating skill/enhancing self-esteem

- real or perceived pressure from management to cut corners

- real or perceived pressure from the workforce (peers) to break rules.

Common modifiers (factors that tend to increase the probability that people will break rules or not follow procedures (Santiago, 2007)) of at-risk behaviour within organisations are:

- poor perception of safety risks

- enhanced perception of benefits

- low perception of potential injury/damage event

- inappropriate management/supervisory attitudes

- low chance of detection due to inadequate supervision

- insufficient accountability

- complacency caused by accident-free environments

- ineffective performance management/disciplinary procedures.

- Where administrative risk controls are necessary, they require significant and ongoing effort by workers and their supervisors (United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 2022). Workers must remain appreciative of and alert to the potential risks within their environment. However, the absence or irregularity of adverse events such as accidents or incidents can lead to a desensitisation to hazards. Passive safety messages and reminding people to follow procedures are not effective risk controls when used in isolation. Procedural adherence is more likely when societal norms dictate the desired behaviour eg, everybody else is following the rules in the workplace. How successfully an organisation manages risks depends on the maturity of their safety management system (SMS) and culture.

Safety management systems and safety culture

- Many international transport regulators require industry participants to implement and maintain a formal SMS that is periodically reviewed as part of regulatory monitoring. Within New Zealand, MNZ requires SOLAS (The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) is an international treaty. SOLAS’s main objective is to specify minimum standards for the construction, equipment and operation of ships, compatible with their safety. Flag States are responsible for ensuring that ships under their flag comply with its requirements) vessels to have an International Safety Management System in place (as required by the International Safety Management Code, the International Maritime Organization’s standard for the safe management and operation of ships at sea) and non-SOLAS vessels to have a certified SMS as part of the Maritime Operator Safety System (MOSS).

- An SMS is an established set of systematic processes to identify hazards and manage safety risks. A common framework for an SMS consists of four independent but interrelated components: safety policy and objectives, safety risk management, safety assurance, and safety promotion.

- An effective SMS will have a tightly coupled relationship between safety risk management and safety assurance (Demming, 2023). The risk management process will provide for hazard identification, risk assessment and treatment of the risk using risk controls. The safety assurance function is vital to ensure that risk controls are achieving their intended objectives of managing risk to an acceptable level.

- One of the primary elements of safety assurance includes the ability to measure and monitor safety performance. To do so effectively requires the collection of a wide variety of both relevant and reliable data to determine whether an organisation’s desired safety outcomes are being met. Data sources include employee hazard and safety reports, findings from safety investigations and audits, safety climate surveys, and operational performance metrics.

- Given much of this information is captured from frontline employees, it is essential that organisations not only have suitable reporting mechanisms in place, but also foster a culture in which employees feel comfortable to raise and report on safety issues. Organisational culture is acknowledged as being the most important factor for shaping safety reporting practices; a healthy safety culture underpins a successful SMS (Maurino, 2017; International Civil Aviation Organization, 2018).

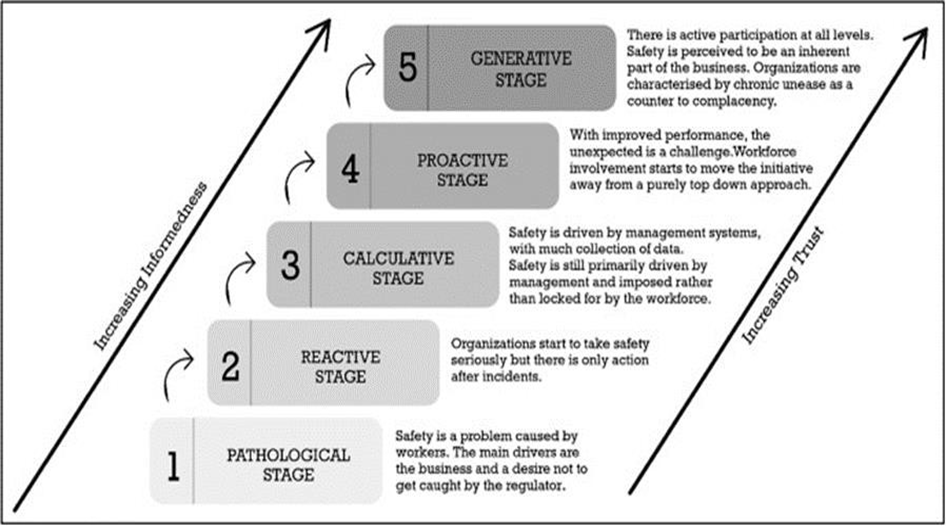

- The safety maturity of an organisation encompasses both its SMS processes and its safety culture. While different models of safety maturity exist, the majority bear a distinct resemblance to the original model, which depicts the various levels of an organisation’s journey from safety naivety to safety maturity (see Figure 6) (Westrum, 1993; Reason, 1997; Hudson, 1999).

- Safety maturity can be measured by examining different elements across each level of an organisation, considering both the tangible components, such as SMS processes, as well as the more abstract qualities of the system, such as safety culture. An example of the former is how an organisation measures its safety performance. Primarily focusing on Lost Time Injury rates (LTIs) – which do not provide a valid or reliable measure of risk, risk drivers or the effectiveness of risk controls – indicates a less mature safety system (Safe Work Australia, 2013). In contrast, utilising a wide variety of appropriate measures, including leading- or predictive-performance indicators across multiple aspects of an organisation’s activity, would reflect a more mature safety system (Kaassis and Badri, 2018).

- A less tangible aspect of organisational safety maturity is related to culture, including the concept of ‘who causes accidents in the eyes of management’ (Parker et al., 2006) At a pathological stage, accidents are either viewed as ‘bad luck’ or as an accepted part of the job. Management sees responsibility as belonging to the individuals directly involved with the accident and employees are blamed and punished when events occur. As safety maturity increases, so does an understanding of the complexities of human behaviour. Management begins to accept a shared responsibility for accidents and blame is replaced with philosophies such as an organisational ‘just culture’. The generative stage of maturity reflects a true comprehension of the nature of human behaviour and a recognition that safety is an emergent property of a complex sociotechnical system.

- The positive correlation between organisational safety culture and safety outcomes is well documented (Zohar, 2010; Bjornskau and Naevestad, 2013). This has led to regulatory authorities in some sectors evaluating an organisation’s safety culture as part of their monitoring and oversight of industry participants (internationally, commercial aviation is a recognised example where this occurs. Within New Zealand this is a requirement for aviation certificate holders).

Summary

- Stevedores work in an environment with numerous and significant hazards. These hazards require effective management to reduce the risk of harm associated with stevedoring activity. The degree to which this can be successfully achieved is largely dependent on the maturity of an organisation’s safety system. Whether an individual organisation can create, maintain and continually improve its safety system will depend on many factors. Two significant factors are the extent of leadership and cohesion within the wider industry, and the way the sector is regulated. These factors are discussed in Section 3 of this report.

Overview of the two accidents

Maritime inquiry MO-2022-203, Port of Auckland

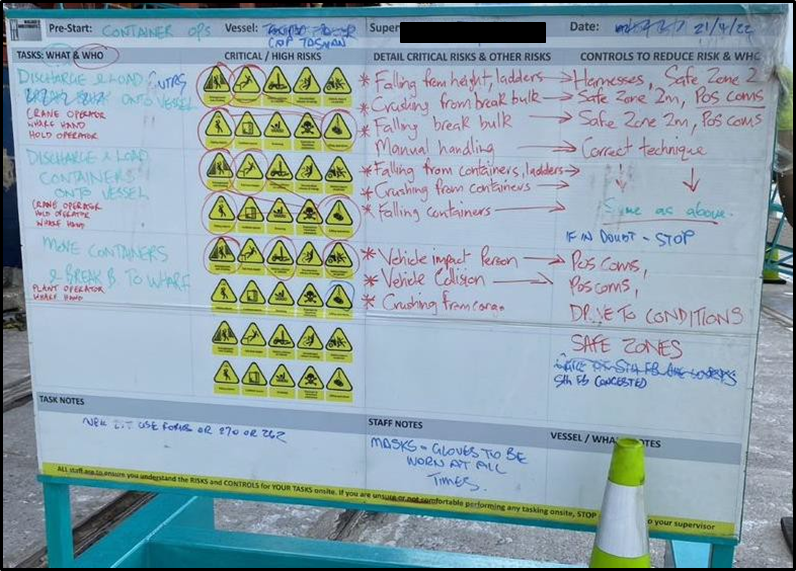

- On 19 April 2022, a stevedore employed by the independent stevedoring company Wallace Investments Limited (WIL) was working as a hold operator onboard the container vessel the Capitaine Tasman, which was berthed at the Port of Auckland’s Jellicoe Wharf. As a hold operator, the stevedore’s job was to help guide the containers into the vessel’s hold and into their correct positions as they were being lowered by the vessel’s crane.

- At the time of the accident, the stevedore was not in sight of either the crane operator or the second hold operator, who was positioned on a different level of the container stack. As the crane operator was manoeuvring a 40-foot container, the stevedore unexpectedly moved under the suspended load and suffered crush injuries followed by a fall from height when the container was lowered.

- WIL had recognised suspended loads as a hazard. The risk controls used were administrative in nature; employees were given training, procedures to follow, and regularly reminded not to position themselves under a suspended load. However, the procedures did not clearly allocate safety responsibilities before giving direction to the crane operator. The presence of at-risk behaviour in the form of non-adherence to procedures also indicated a desensitisation to workplace hazards and a lack of effective supervisory oversight.

- WIL’s SMS was still in development and had not reached the level of maturity required to provide assurance that risk controls were adequate or that all hazards were being identified. The regulatory framework did little to support the ongoing development of WIL’s SMS, nor was the level of regulatory oversight sufficient to provide assurance of WIL’s future safety performance.

- See Appendix A for details of the Commission’s inquiry MO-2022-203.

Maritime inquiry MO-2022-202, Lyttelton Port

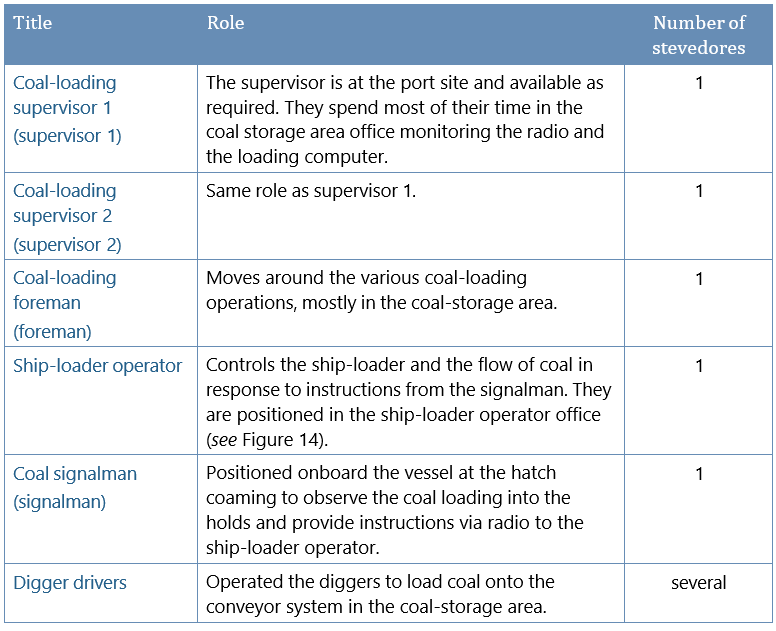

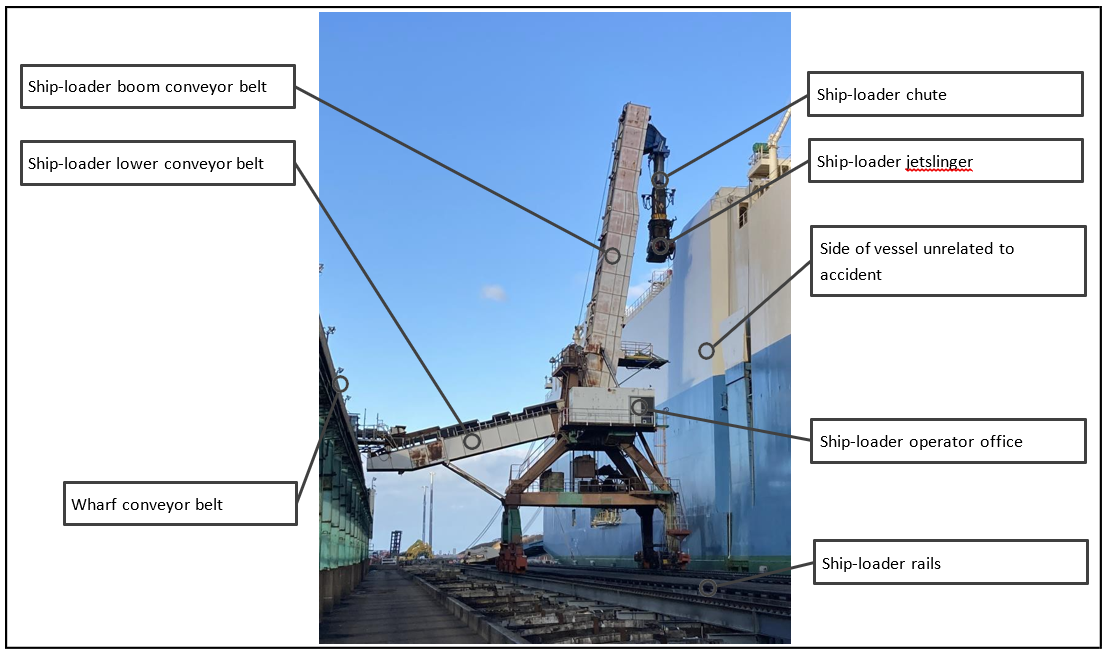

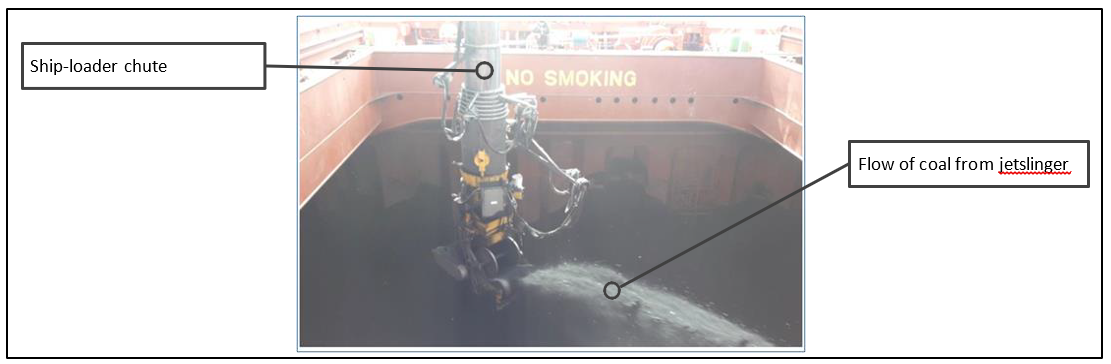

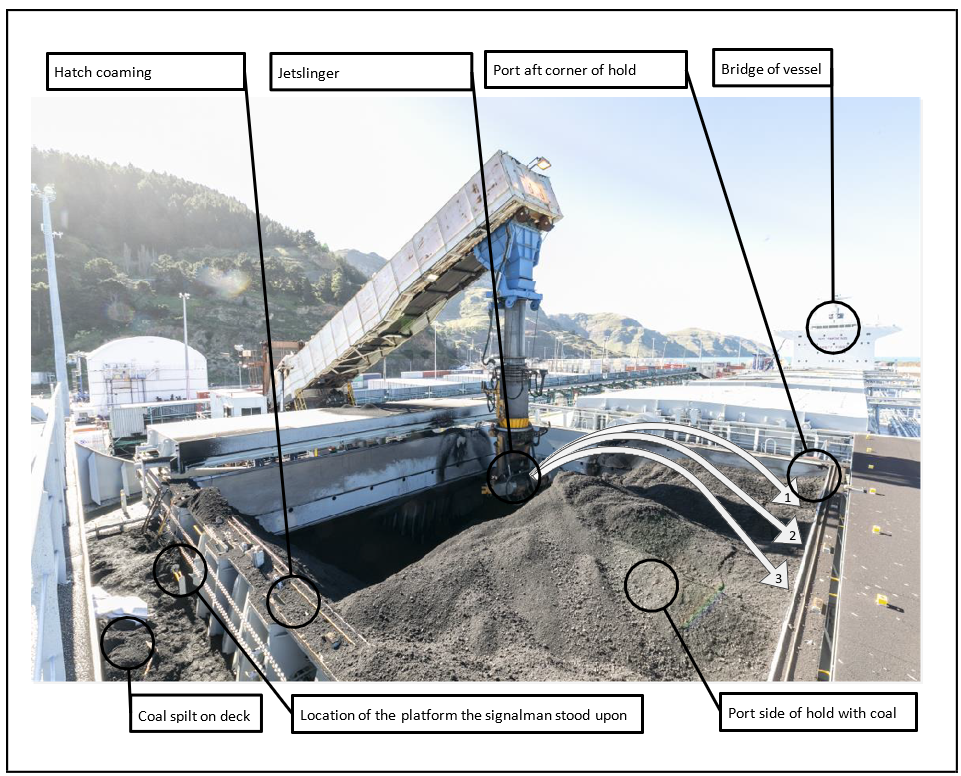

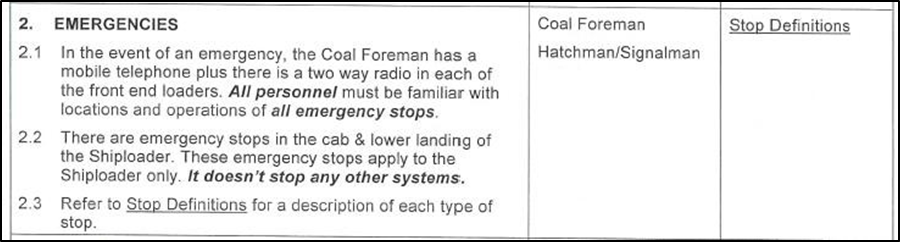

- On the morning of 25 April 2022, a stevedore employed by the Lyttelton Port Company Limited (LPC) was working onboard the bulk carrier ETG Aquarius, which was berthed at the Lyttelton Port coal-loading berth. The stevedore was part of a gang that was loading coal into the number one hold of the vessel. As the coal signalman, the stevedore’s job was to monitor the flow of coal from a conveyor belt into the hold.

- At the time of the accident, the coal signalman was not in sight of any of the other gang members, including the stevedore who was operating the machine delivering the coal to the hold. During the final stages of loading coal into the hold, radio communication was lost between the coal signalman and the stevedore operating the coal-loading machine. The coal signalman was subsequently found buried under coal that was accumulating on the vessel’s deck.

- LPC had taken significant steps to improve safety of its port operations before the accident occurred. It was in the first year of a three-year programme to improve its SMS in regard to risk identification and management. At the time of the accident, LPC had not identified all the critical risks of the coal signalman’s role, which meant that the associated risks, such as medical fitness or working in physical isolation, were not explicitly addressed. The risk mitigation strategies that were in place for the associated risks tended to rely upon informal administrative risk controls, which were not always well articulated within the SMS.

- The training system did not ensure that all staff had a thorough understanding of the associated risks and their mitigation measures, reducing the effectiveness of those risk controls. This was compounded by passive supervision of the coal signalman, which did not ensure compliance with risk controls and safety-critical procedures.

- The regulatory framework did not encourage proactive support, monitoring or assessment, via review or otherwise, of LPC’s SMS to ensure its effectiveness.

- See Appendix B for details of the Commission’s inquiry MO-2022-202.

Commonalities between the two accidents

- Despite the difference in the type of stevedoring activity taking place when the accidents occurred, each of the Commission’s inquiries found notable similarities regarding how safety was being managed at an organisational, industry and regulatory level.

- At an organisational level, the risks associated with work activity were primarily being managed with administrative risk controls, yet robust safety assurance processes to ensure that these controls remained effective over time were lacking. As a result, neither LPC nor WIL adequately understood how the day-to-day behaviour of their employees reduced the effectiveness of the already vulnerable administrative risk controls.

- Both organisations were attempting to improve their SMSs. However, a lack of industry cohesion meant there was little ability to benchmark with others in the industry. With no best practice guidelines, no minimum training requirements, and few safety-related information-sharing platforms, leadership from within the sector was found lacking.

- Neither organisation received a satisfactory level of proactive regulatory oversight of their stevedoring operations. Most regulatory interactions were limited to LPC and WIL reporting their notifiable events under HSWA legislation, and to any subsequent follow up by MNZ and WorkSafe because of those notifications. Reactionary reporting and associated regulatory sanctions provide little insight into the health of an organisation’s safety system or assurance of future safety performance. Nor does it encourage the sharing of information within the industry to support safety across the sector.

- Section 3 considers common safety issues for the New Zealand stevedoring industry.

Safety issues for the New Zealand stevedoring industry Ngā take haumanu mō ngā kaitītaritari o Aotearoa

- Safety issues are an output from the Commission’s analysis. They may not always relate to factors directly contributing to the accident or incident. They typically describe a systemic problem that has the potential to adversely affect future transport safety.

- The two accidents investigated by the Commission occurred in different operational contexts. The Auckland accident involved a private stevedoring company fulfilling a contract to a shipping company and the Lyttelton accident involved stevedores directly employed by the port company. The natures of the stevedoring activities were also different; one involved loading containers using the vessel’s crane, and the other involved loading a bulk carrier using port infrastructure and equipment.

- Despite the different operational contexts, the Commission identified common safety issues. Both accidents revealed organisational weaknesses in risk identification and mitigation strategies, communication and supervisory oversight.

- There are thirteen ports and five private stevedoring organisations in New Zealand. The Commission acknowledges that a sample of two is not necessarily representative of how other port and stevedoring organisations conduct their activities or manage safety. Nevertheless, the systemic issues identified in the two inquiries suggest that the industry has not yet reached the level of maturity required to support all participants

- The safety issues identified have previously been identified in Australia following a stevedoring accident on a container vessel in 2010. The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) investigated the accident and in its report (Australian Transport Safety Bureau, 2011) commented:

A system of safety is a feature of an industry or sector rather than of an organisation and is defined by the shared safety objectives of key stakeholders resulting in a systemic approach to reducing risk in the workplace. Complementary roles and operations of stakeholders promote the system and introduce multiple layers of defences to prevent adverse occurrences. These layers of defence start at the regulatory level, with laws and codes of safe practice, pass through industry bodies all the way down to the training of personnel, safe operating procedures and the mindset of people involved in the operations ‘at the coal face’. While a system of safety is more than one specific organisation, the attitudes of personnel at all levels of individual organisations are vital for the ongoing success of any system of safety. The combined effect of legislation and its effective implementation in the workplace, and the attitude of personnel towards safety, enhance both the organisational culture and safety culture within an organisation.

- The ATSB’s comment is equally applicable to the New Zealand stevedoring industry. It is the Commission’s view that a holistic approach, which includes investment by both the regulatory system and industry, is required to rectify the safety issues identified in these investigations.

Safety issue: Stevedoring is a high-risk activity, yet it is not regulated with the same degree of rigour as other comparable industries. The current degree of regulatory oversight is not sufficient to ensure the safety of stevedoring activity.

- Internationally, working on the waterfront has long been recognised as a hazardous occupation (International Labour Office, 2018). The introduction of container shipping significantly reduced the number of personnel required to undertake traditional stevedoring tasks; yet in the 50 years since many countries have still grappled with unacceptable rates of harm in their port workforce. Automation and technology within the port environment afford future opportunities to improve safety; however, both the cost and associated complexities mean that stevedores will continue to work for some time to come in settings where there are numerous hazards.

- Stevedoring is inextricably connected to maritime operations; stevedores undertake many of the same or similar duties as seafarers, and they face comparable risks in the port environment. In contrast to stevedoring, seafaring is regulated through legislation, specifically the Maritime Transport Act 1994 (MTA). The MTA prescribes risk-mitigation controls and requires regular auditing of certified SMSs against specified criteria for seafarers.

- Regulation of stevedoring activity is under the much broader HSWA. Some of the activities that stevedores are engaged in are specifically regulated. However, unlike other high-risk industries regulated under HSWA, there are no tailored requirements for stevedoring, either in the form of Regulations (eg, Health and Safety at Work (Adventure Activities) Regulations 2016; Health and Safety at Work (Mining Operations and Quarrying Operations) Regulations 2016; Health and Safety at Work (Petroleum Exploration and Extraction) Regulations 2016), Approved Codes of Practice (ACOP) (eg, Approved Code of Practice for Safety and Health in Forest Operations), Safe Work Instruments (SWI) (A Safe Work Instrument is a form of legislation that supports or complements regulations. Safe work instruments have legal effect only where they are referred to in regulations eg, Health and Safety at Work (asbestos - Prescribed Relevant Courses) Safe Work Instrument 2017), auditable SMSs (eg, gas supply systems) or Safety Case approvals (Major hazard facilities).

- Regulation for stevedoring organisations under HSWA is performance-based; it is up to each individual PCBU to decide how they will meet the HSWA requirements. This type of safety regulation is generally recognised as being positive in terms of flexibility and innovation, allowing organisations to set and manage their own safety processes without being overly prescriptive and regulatorily burdensome (May, 2003). However, it is also recognised that the success of performance-based regimes depends upon a regulator’s capability to measure and monitor outcomes (Cogilianese 2017; Natural Resources Canada, 2013).

- Within HSWA, there are a number of mechanisms for regulators to provide leadership and oversight, including:

- ensuring appropriate scrutiny and review of stevedoring activity

- promoting the provision of advice, information, education, and training in relation to work health and safety

- providing a framework for continuous improvement and progressively higher standards of work health and safety.

- Another way for regulators to gauge the safety performance of industry participants is to formally assess and routinely review their SMSs, similar to the approach taken in New Zealand’s commercial maritime sector.

- Currently, there is no requirement for stevedoring organisations to have an assessment of their internal safety systems or be periodically reviewed by the regulator to ensure safety objectives are being met. Performance-based regulation typically works well within industries with mature safety systems; however, stevedoring does not enjoy this level of safety maturity. While there is a certain amount of information sharing between industry participants, this has not yet reached the level required to enable effective safety-related data analysis or agreement on best practices.

- In essence, the stevedoring sector operates between two quite different frameworks; activity is not audited as it would be under prescriptive frameworks, nor is it subject to formal safety management oversight and monitoring as required by some other industries that operate within a performance-based system. Whether a stevedoring organisation’s SMS is effective or not therefore relies on the organisation’s level of safety proficiency. Organisations must not only be motivated to have a robust SMS but must also know how to implement, execute and maintain that system appropriately. Both WIL and LPC were in the process of improving their SMSs, yet they were doing so without the benefit of the regulator monitoring or providing a thorough assessment or questioning the effectiveness of their systems (see Appendices A and B).

- In 2019, MNZ and WorkSafe began joint HSWA assessments of New Zealand’s 13 major commercial ports, which included an assessment for both LPC and POAL. Other proactivity by the regulators included several focused safety campaigns relating to dangerous goods, loading and unloading of high-risk cargo, COVID-19 requirements, and the development of Fatigue Risk Management guidance. However, there was no effective monitoring and assessment to ensure individual stevedoring organisations were managing their safety risks appropriately. Regulatory oversight of safety management was primarily focused on reactive interventions following notifiable events rather than proactive assessment and monitoring (Information provided by MNZ indicates that, while maritime officers engaged with port and stevedoring companies, most port-related oversight focused on vessel inspections). Notifying a regulator of events when legally obliged provides little useful information about the current or future state of an organisation’s safety performance. The Commission does not consider this level of regulatory oversight is appropriate for an industry where the rate of workplace harm is disproportionately high on both a national and an international front.

- In the absence of a ‘just culture’ approach by regulators, it is unlikely stevedoring organisations are willing to voluntarily share their safety information beyond that required by legislation. The negative repercussions associated with regulatory prosecution as a deterrence have been well documented (see Dekker, 2011; Heraghaty et al., 2021). This has led to some regulators acknowledging the importance of striking a balance between the imposition of sanctions and the need for data from their industry participants (eg, The New Zealand Civil Aviation Authority and the Australian Civil Aviation Safety Authority). While sanctions hold a valid place in regulatory frameworks, the Commission surmised that stevedoring participants view the regulator as being overly focused on prosecutions whilst providing little educational leadership for this sector. The Commission considers that this has done little to incentivise safety leadership and growth within the stevedoring community.

- The Commission has made a recommendation to address this safety issue in Section 5 of this report. In support of this recommendation, the Commission also makes the following observation. At the time of the accident, WorkSafe regulated stevedoring activity that occurred on the wharf and MNZ regulated stevedoring activity on the vessel. The relationship between WorkSafe and MNZ was managed in part through a Memorandum of Understanding. However, the Commission considers that this arrangement had inherent issues in providing robust safety oversight for an industry that requires a higher level of regulatory stewardship than currently takes place. These issues were recognised by both WorkSafe and MNZ in discussions with the Commission.

- The Commission acknowledges the work done by the Port Health and Safety Leadership Group in identifying ways to address harm on New Zealand ports.

- In April 2023, the Government agreed to extend the HSWA designation of MNZ beyond the existing designation for work onboard ships, to also include work at commercial ports handling containers, logs and/or bulk cargo, excluding major hazard facilities (major hazard facilities are defined under Health and Safety at Work (Major Hazard Facilities) Regulations 2016) at these ports. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment is currently working with other relevant agencies to draft the designation instrument, with the expanded MNZ designation expected to come into effect on 1 July 2024.

-

On 3 July 2023, WorkSafe informed the Commission of the following:

To support the decision that Maritime New Zealand’s (MNZ’s) designation will be extended from July 2024 to cover all the major ports, WorkSafe and MNZ have agreed a co-ordinated operational approach in respect of proactive assessment activities in ports. This co-ordinated approach will support MNZ to build its capability to take on the extended designation role over the next year. During this time, the agencies will carry out proactive co-ordinated assessment activity across the 13 international ports. This will be jointly planned to enable WorkSafe and MNZ presence during these assessments. Each quarter, areas of focus for the assessments will be jointly agreed. The agreed focus areas, to date, align with some of the key risks identified in the Ports Sector Insights Picture and Action Plan:

From March to June 2023 – a focus on traffic management and working in and around vehicles

From July to September [2023] – a focus on suspended loads, stacking, and hazardous substances.

In October, the agencies will jointly review the outcomes of the work to date, and review the focus areas for the next quarters through to July 2024. While focus areas are set for assessment activity, either agency’s inspector may identify, and follow up as appropriate in line with operational practice, any particular immediate risks noted during an assessment visit.

Safety issue: The New Zealand stevedoring industry lacks consistency regarding safe work practices:

While international benchmarking is available, New Zealand does not have agreed guidelines on best practices for stevedoring.

- Internationally, there are several documented health and safety standards available for port work. Previously, these documents tended to lack detail or were considered too generic to be useful in a practical sense (see Australia Transport Safety Bureau (2011) for discussion of inadequacy of international guidance, such as that previously provided by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the International Cargo Handling Coordination Association (ICHCA)). In the last decade, however, there has been an increase in more detailed guidelines in the form of best practices, including:

- International Labour Organization (ILO) Code of Practice: Safety and Health in Ports (International Labour Office, 2018)

- Safe Work Australia: Managing Risks in Stevedoring Code of Practice (2016)

- Health and Safety Executive (UK): Approved Code of Practice Safety in Docks (2014)

- Port Skills and Safety (UK): SIP003 Guidance on Container Handling

- Health and Safety Authority (Ireland): Code of Practice for Health and Safety in Dock Work (2016)

- US Pacific Coast Marine Safety Code (2014).

- No similar guidance has been developed in New Zealand. The closest document is the Code of Practice for Health and Safety in Port Operations, prepared in 1997 by the Port Industry Group conjointly with the then Department of Labour’s Occupational Safety and Health Service and the Maritime Safety Authority.

- This was a proactive initiative by industry at the time. However, legislation has since been amended and views on safety management have changed, making this Code of Practice obsolete. Information provided to the Commission indicates that some personnel involved in stevedoring safety management either do not know about this Code of Practice or consider it no longer fit for purpose.

- The argument for an approved Code of Practice, rather than relying on industry guidance material, has previously taken place in Australia. In 2013, following what the industry recognised as an unacceptably high accident and fatality rate for port workers (at the time the average death rate for stevedores in Australia was 14.3 per 100,000 workers in comparison to 2.8 per 100,000 workers for construction and 1.05 per 100,000 workers on average. The Maritime Union of Australia also claimed that the fatality rate for stevedores was more than double that of the Australian Defence Force, including those serving in Afghanistan), Safe Work Australia considered several options to improve safety within the sector that, like New Zealand, had dual regulation (the Australian regulator at the time (AMSA) had jurisdiction over seaworthiness of vessel technical standards, including ship lifting equipment (cranes), yet stevedoring workers and their systems of work fell under the relevant state or territorial Workplace Health and Safety (WHS) legislation). A cost benefit analysis found that the adoption of an approved Code of Practice would provide a significant reduction in the number of serious harm events. The predicted safety improvements across a 10-year period were comparable to those estimated to occur if specific health and safety regulations were developed for stevedoring, but without the associated regulatory burden (Safe Work Australia, 2015).

- Within New Zealand, adoption of a Code of Practice has been shown to be effective for other parts of the port sector. The New Zealand Port and Harbour Marine Safety Code 2020 is an example of a successful tripartite relationship between regional councils, port operators and the regulator, MNZ. This Code of Practice is a voluntary national standard that provides a framework to manage the safety of port and harbour activities, although stevedoring is not included (the Code focuses primarily on safe passage of ships navigating in New Zealand ports and harbours).

- Recognising that there is no regulatory requirement for port organisations to have a certified SMS, this Code of Practice ‘promotes a systems approach to the management of safety to ensure that risks are identified and managed in a structured and sustainable way that fosters continuous improvement’ (New Zealand Port and Harbour Marine Safety Code 4.1(a)). This includes a dedicated work programme to support robust safety management practices within the harbour environment. Key principles for managing safety risk have been established (Key Principles for Marine Safety Risk Management.), along with best practice guidelines for specific port activities.

- To assess whether individual ports are appropriately managing their risks, an annual report on the performance of their SMS is submitted to the Secretariat. Additionally, an independent panel reviews each port’s SMS. The individual results remain confidential, but where good safety management practices are identified, these are shared more widely.

- While this Code of Practice is only voluntary it demonstrates how, in the absence of any regulatory requirements to do so, industry stakeholders can come together to establish their own safety standards and share good practice to improve their working environment. At the time of these accidents, neither WIL nor LPC had access to a suitable New Zealand common code of practice for stevedoring. The Commission considers that, whilst operating under the performance-based HSWA legislation, an approved code of practice would benefit the New Zealand stevedoring industry. The Commission has therefore made a recommendation in Section 5 of this report to address this safety issue.

There are no minimum training standards for entry to and progression within the industry.

- Following the regulatory changes in the late 1980s, the stevedoring industry became privatised and there was no longer a common pool of stevedoring labour. This was not unique to New Zealand and the International Labour Office (the International Labour Office is the permanent secretariat of the International Labour Organization) commented that ‘privatisation of the industry has led to considerable changes in the organisation of ports and the employment of people in them, including an increased use of non-permanent workers’ (International Labour Office, 2018).

- This privatisation increased the industry’s reliance on transient and low-experience workers, which did not lend itself well to hazardous occupations such as port work. Statistical analysis of 25 years of safety data at Genoa port (Italy) found a relationship between the ‘strikingly’ high increase of young and/or low-experience workers and the ‘remarkable’ increase in risk of occupational injuries (while the change in port infrastructure to accommodate containerised vessels reduced approximately 80% of the workforce between 1980 and 2006, the percentage of low-experience workers increased from 28% to 74% and injuries per hundred thousand hours worked increased from 13.0 to 29.7 (Fabiano et al., 2010)). This risk could be mitigated with training, however there are currently no minimum training requirements to work as a stevedore in New Zealand.

- The lack of training requirements for stevedores is in stark contrast to vessel crew members who also conduct stevedoring-related activities. While the training standards for crew reflect their remote work environment when at sea, many of the hazards are the same, such as working in confined spaces and at heights and handling dangerous goods.

- While some NZQA qualifications exist for stevedoring, they are not compulsory. Furthermore, some stevedoring organisations found the NZQA framework presented difficulties, particularly that NZQA cannot issue individual unit standards unless an employee is enrolled in the certificate programme. Effectively, an organisation wanting to train their stevedores in a particular area has to enrol each employee in the certificate programme, regardless of inclination or abilities to complete a Level 3 qualification. This is further exacerbated by industry issues such as an aging workforce and difficulty recruiting into the sector.

- For the most part, training is conducted through on-the-job shadowing of other stevedores (see Appendices A and B). The lack of common standards for stevedoring activity invariably results in training to different levels, not only within ports, but within gangs. Information gathered during the Commission’s investigations of these two accidents found that communication standardisation was particularly problematic. Some stevedores reported they were taught different communication techniques depending on who they happened to be shadowing at the time. Others reported becoming confused on occasion when they received different signals from multiple people at one time; deciding which instruction to follow may simply have been based on which stevedore they trusted most.

- A lack of training standards for progression within the stevedoring industry is also a concern. Unlike mariners, who require formal assessment before taking on additional responsibilities, there is no such requirement for stevedores. For supervisors to be effective, they should possess the correct technical skills and leadership ability. If there are no training competencies required to become a supervisor, it is difficult to assess how well-equipped those individuals are to perform this safety-critical role.

-

Under HSWA, a PCBU must ensure training protects employees from health and safety risks arising from work activity. Given the lack of standardisation of stevedoring activity, this presents significant challenges for the industry. This has previously been highlighted by the Maritime Union of Australia to support the inclusion of training provisions in the Australian Code of Practice:

there is strong support within the maritime community for detailed training guidance. Of the approximately 700 submissions made during the last comment phase, an overwhelming majority argued for better training… [training provisions] should remain within the code as an illustration of how a Person Conducting a Business or Undertaking (PCBU) might satisfy the [WHS Act] (https://www.mua.org.au/news/submission-safe-work-australia-national-stevedoring-code-practice).

- The absence of minimum training standards has created a divergent workforce with little incentive to standardise in a market of increased commercial competition. Unlike those in other high-risk industries that must factor in the cost of training and maintaining qualifications to adhere to industry standards or regulations, the stevedoring sector does not. The Commission has therefore made a recommendation in Section 5 of this report to address this safety issue.

There is minimal proactive gathering and sharing of safety information in the industry.

- The stevedoring sector attempts to work collaboratively through the Port Industry Association (PIA). Information sharing is encouraged through a range of forums and workshops, and information on potential safety hazards, such as vessel equipment deficiencies, can be circulated to members. At the time of these accidents, however, information sharing conducted in a consistent and effective manner was still in its infancy.

- One of the benefits of a cohesive industry is the ability to share safety learnings. Currently, there is limited facility either internationally or domestically to share safety-related information. An example of this was the use of a lashing platform at Hamburg’s Altenwerder terminal, which made twist lock handling considerably safer, yet this was not introduced at many other container ports (International Transport Forum, 2021).

- Information provided to the Commission suggests that while some safety lessons are shared, the benefits of a good safety culture are not as well socialised in the stevedoring industry compared to other more mature industries where participants are considered high-reliability organisations. There is limited incentive to share information with the regulator beyond what is legally required, and this does little to encourage safety leadership for participants in a highly competitive industry. If the threat of prosecution is always imminent, it is understandable why those on the front line may not want to report safety-related information, even within their own organisations.

- The benefits of increased safety reporting extend beyond the response and management of an individual event to enabling trend monitoring and proactive risk management across the sector. This would require the stevedoring industry to fully embrace the philosophy of SMSs, where safety is considered a core business function. Within an SMS, safety and efficiency are not in competition; the management of safety is afforded the same importance as other business processes, resulting in a realistic allocation of resources to ensure protection of the organisation’s production goals. This in turn creates increased efficiencies.

- By sharing insights and lessons learned, stevedoring stakeholders would learn from one another's experiences and make improvements that would benefit the entire sector. Additionally, by promoting a culture of continuous learning and improvement, stevedoring organisations could work together to identify and mitigate risks, and ultimately increase overall safety of the industry. The Commission has therefore made a recommendation to address this issue in Section 5 of this report.

Safety actions Ngā take haumanu me ngā mahi whakatika

General

- Safety issues may be addressed by safety actions taken by a participant. Otherwise, the Commission may issue a recommendation to address the issue.

Accident at Port of Auckland

- The Commission believes action needs to be taken to ensure the safety of future operations. Therefore, the Commission has made a recommendation to WIL in Section 5 of this report.

Accident at Lyttelton Port

- On 27 June 2023, LPC advised the Commission that following the accident (detailed in Appendix B) it carried out an extensive risk assessment and made a number or changes to the coal-loading process, including implementing a number of engineering controls to the plant involved in the coal-loading operation.

- LPC has also proposed the following safety actions:

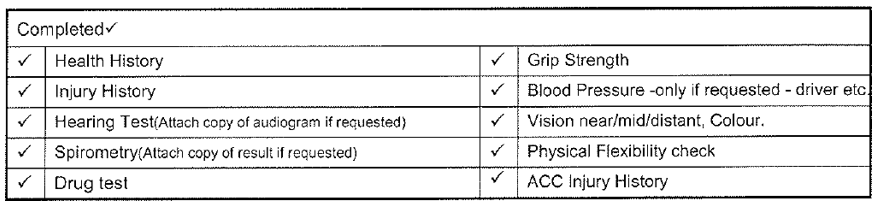

- Development and implementation of a suitable Fitness for Work programme and related processes to monitor for changes and reduction in functional fitness that may affect an employee’s ability to safely perform the tasks required

- establish role-specific fitness and medical requirements

- engage with the workforce to introduce annual medical assessment

- Identification of any additional significant risks at LPC and inclusion of these in its SMS, and independent verification as part of the Material Risk Assurance programme.

- Development and implementation of an LPC Learning and Development Policy, and a Learning and Development system that includes specific:

- training needs analysis

- verification of competency

- enhanced supervisor training, clarifying roles and responsibilities in relation to the requirements of HSWA.

- Development and implementation of a suitable Fitness for Work programme and related processes to monitor for changes and reduction in functional fitness that may affect an employee’s ability to safely perform the tasks required

- The Commission welcomes the safety action to-date. However, it believes more action needs to be taken to ensure the safety of future operations. Therefore, the Commission has made a recommendation in Section 5 of this report to address this issue.

Industry-wide safety action

Port sector insights

- As a response to the accidents in Auckland and Lyttelton, the Minister of Transport requested the Port Health and Safety Leadership Group provide the Minister with advice on a collective set of actions, including regulatory standards, to address harm at New Zealand ports.

- The Leadership Group was made up of port and stevedoring companies, unions, the Port Industry Association, MNZ and WorkSafe representatives. The vision of the Leadership Group was to deliver ‘A high performing, resilient port sector, where people thrive and worker health and safety is prioritised through high-trust, tripartite collaboration’.

- In November 2022, the Leadership Group presented the Minister with the Port Sector Insights Picture and Action Plan. The Action Plan provided six initial actions focused on addressing some of the issues identified, including:

- developing an Approved Code of Practice on Stevedoring

- implementing the Fatigue Risk Management System Good Practice

- extending MNZ’s HSWA designation on ports

- addressing workforce issues and skills

- improving incident reporting, notifications, insights and learnings across the sector

- developing opportunities to share good practice.

-

On 13 July 2023, MNZ gave the Commission further information about the action plan, specifically:

The action plan has six focus areas which address many of the changes the report suggests are need in the stevedoring sector:

- Standards and guidance with a priority to develop an approved code of practice (a draft ACOP is being developed, led by Maritime NZ - there have been industry workshops as part of its development and a draft will be out for broad consultation August/September 2023).

- Fatigue management (guidance on a Fatigue Risk Management System has been introduced and an implementation programme to support the uptake of the sector is being action).

- Clarifying regulator arrangements (Cabinet agreed in April that Maritime NZ would be the responsible regulator for ports from 1 July 2024).

- Workforce sustainability with the priority action to develop new, or refine existing courses and unit standards to cover critical roles and activities on ports (Content being developed for a Port Safe Start Micro Credential is underway and skills gaps in sector are being mapped. Further work is also being considered looking at career pathways and what regulatory support might be needed to encourage uptake of training).

- Incident Notification, Insights and Intelligence with a priority action to encourage consistent, timely reporting of incidents and notifications; share information around unsafe ships; and develop an on-going insights and intelligence picture on port sector harms (work is currently being scoped).

- Good practice with a priority action to develop a “depository” of good practice that can be built on over time to be a resource for the port sector to learn from others to develop innovative practices (as part of the Port Health and Safety Leadership Group insights picture and action plan a suite of good practice was pulled together. Work is being considered on where to place, and share, good practice and how to add to it over time).

- The Commission welcomes the safety action to-date. However, that action is yet to be completed and the Commission believes more is needed to ensure the safety of future operations, including the way the sector is regulated. Therefore, the Commission has made two recommendations in Section 5 of this report to address this issue.

Recommendations Ngā tūtohutanga

General

- The Commission issues recommendations to address safety issues found in its investigations. Recommendations may be addressed to organisations or people and can relate to safety issues found within an organisation or within the wider transport system that have the potential to contribute to future transport accidents and incidents.

- In the interests of transport safety, it is important that recommendations are implemented without delay to help prevent similar accidents or incidents occurring in the future.

New recommendations

- On 22 August 2023, the Commission recommended that Maritime New Zealand works with industry stakeholders to improve safety standards for stevedoring operations through:

- implementing an Approved Code of Practice for managing health and safety risks associated with stevedoring activity

- establishing minimum training standards for stevedores

- establishing a programme to facilitate continuous improvement of stevedoring safety standards, including the sharing of safety information amongst industry stakeholders. (024/23)

- On 27 September 2023, the Commission recommended that Maritime New Zealand and WorkSafe (until 1 July 2024) ensure that their regulatory activity includes a proactive role (such as monitoring and assessment) in the safety of the stevedoring industry. (025/23)

- On 22 August 2023, the Commission recommended that Wallace Investments Limited prioritise a review of their safety management system to ensure that:

- the responsibility for safety of each stevedoring role is clearly defined, unambiguous, and understood by all personnel

- procedures for work activity adequately cover scenarios with increased risk

- all risks are identified, and administrative risk controls are only used when more effective risk controls are not reasonably practicable

- adherence to administrative risk controls is effectively managed.

- supervisory oversight is effective and not compromised by competing operational demands

- safety-assurance mechanisms are in place to reliably evaluate the effectiveness of and adherence to risk-control strategies. (026/23)

- On 22 August 2023, the Commission recommended that Lyttelton Port Company Limited reviews the medical screening of stevedores to ensure it provides adequate assurance of medical fitness for their duties and responsibilities. (027/23)

-

On 13 September 2023, Lyttelton Port Company replied:

On 22 August 2023, the Commission recommended that Lyttelton Port Company reviews the medical screening of stevedores to ensure it provides adequate assurance of medical fitness for their duties and responsibilities.

Accepted: The recommendation was accepted (wholly or in part) and is being, or will be, implemented

Description of the action taken:

- Design of the LPC Fitness for Work programme

- Introduction in February 2023 of mandatory medical fitness assessments for new employees and will be mandated for all employees by the end of July 2024

- Employment of a dedicated Occupational Nurse to lead the LPC Fitness for Work programme

- Awareness campaign for LPC Fitness for Work Programme

- Consultation with workforce for LPC Fitness for Work programme

- Consultation with Union for LPC Fitness for Work programme

-

Currently offered to all operational deployment of the LPC Fitness for Work programme to all operational staff

Date of expected implementation

End of July 2024

On 22 August 2023, the Commission recommended that Lyttelton Port Company Limited prioritises a review of their safety management system to ensure that:

- documented procedures are consistent and reflect all critical aspects of the work as done

- all risks are identified, and administrative risk controls are only used when more effective risk controls are not reasonably practicable

- adherence to administrative risk controls is effectively managed

- supervisory oversight is effective and not compromised by competing operational demands

- radio communications used for safety-critical tasks are consistent and reliable. (028/23)

-

On 13 September 2023, Lyttelton Port Company Limited replied:

On 22 August 2023, the Commission recommended that Lyttelton Port Company prioritises a review of its safety management system to ensure that documented procedures are consistent and reflect all critical aspects of the work as done.

Accepted: The recommendation was accepted (wholly or in part) and is being, or will be, implemented

Description of the action taken:

- The appointment of a Training Manager for Lyttelton Container Operations

- Review of training material, Safe Work Method Statements, and operational procedures to reflect all critical aspects of work.

- Introduction of improved document control processes

Date of expected implementation

End of Feb 2024

On 22 August 2023, the Commission recommended that Lyttelton Port Company prioritises a review of its safety management system to ensure that all risks are identified, and administrative risk controls are only used when more effective risk controls are not reasonably practicable.

Accepted: The recommendation was accepted (wholly or in part) and is being, or will be, implemented

Description of the action taken:

- All operational risk registers are undergoing a current review as part of the wider migration to LPC’s new integrated Safety Management System

- Indication of the actions intending to take.

- Identification of administrative controls and review to see if higher hierarchy of controls are suitable.

Date of expected implementation

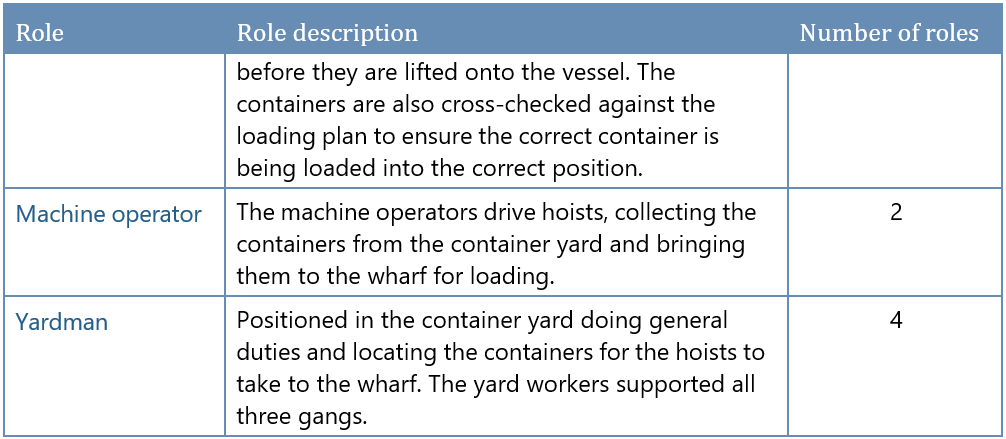

End of Feb 2024