PASSENGER SHIP SAFETY

Review of Operational Safety Measures to Enhance the Safety of Passenger Ships Submitted by ICS

Introduction

1. In response to the outcomes of MSC 90 and MSC 91 ICS recommended that member passenger ship operating companies conduct a review of operational safety measures. The recommendations provided at annex to MSC.1/Circ.1446 and the further recommendations within MSC.1/Circ.1446/Rev.1 were used as a basis for the review, however, additional aspects of passenger ship vessel operations were also considered and enhancements and best practice reported.

2. Recognising that the SOLAS definition of a passenger ship is “a ship which carries more than twelve passengers”, this submission reports on reviews by companies operating different types of passenger ships, including Ro-Ro Passenger ships and High Speed Craft and is not part of the Cruise Industry Operational Safety Review reported by CLIA in MSC 92/6/1.

3. The results of the reviews conducted by companies are summarised below and recommendations are made in some cases as a direct result of findings from the reviews. In addition, companies reported on other policies and procedures that they reviewed after the Costa Concordia accident.

Lifejackets on board Passenger Ships, except Ro-Ro Passenger Ships

4. Taking into account that the recommendation in MSC.1/Circ.1446 for companies to consider additional lifejackets was explicitly not applicable to Ro-Ro Passenger ships, these operators conducted a review to ensure that the location and accessibility of the additional lifejackets required by SOLAS were appropriate.

5. One issue identified, now rectified, was the absence of suitable signage for oversized lifejackets or lifejacket accessories to ensure compliance with the requirements of SOLAS Chapter III Regulation 7.2.1.5.

6. The distribution of lifejacket sizes was also considered for each assembly station to ensure accessibility, and that an appropriate number of oversized lifejackets or accessories to ensure compliance with SOLAS III/7.2.1.5, adult, child and infant lifejackets were available at each assembly station.

Recommendations

7. SOLAS specifies carriage requirements for lifejackets, however, there is no existing requirement or guidance for the location and distribution ratios for the different types of lifejackets. It is therefore recommended that guidance is developed on issues to consider when determining the distribution of lifejackets in each assembly station. Consideration of these issues could take place when conducting evacuation analysis.

8. It is also recommended that consideration should be given to ensure that there should only be one style of lifejacket that can be donned in a similar manner (irrespective of the manufacturer) on board for passengers. The goal of this recommendation is to avoid confusion amongst passengers and crew when donning lifejackets.

Emergency Instructions to Passengers

9. Companies identified that emergency instruction language provision was sufficient for their ships and noted that the extent of information provided in different languages is determined on a case by case basis. Planning based on passenger demographics was seen as important.

10. It was reported that in recent incidents where passengers were mustered as a precaution, passengers had confirmed their understanding of emergency information and instructions.

11. It has been highlighted that some vessel types, and in particular High Speed Craft utilise videos to supplement the provision of emergency instructions. In addition some companies use emergency information cards to complement information required by SOLAS. It is noted that the High Speed Craft Code requires such information to be provided “near each seat”.

12. It was also noted that emergency information is reinforced by announcement and by trained crew during an emergency and at passenger assembly.

Recommendations

13. It is recommended that companies consider extending the use of an accompanying video for passenger emergency instruction notices, where appropriate. It is also recommended that emergency information cards are made available for passengers, on request, that complement the information required by SOLAS.

Common Elements of Musters and Emergency Instructions

14. Companies reported that they had increased their focus on training and drills to ensure crew are able to provide assistance to disabled persons and persons with reduced mobility.

Passenger Muster Policy

15. Companies reported that the policy within MSC.1/Circ.1446/Rev.1 was in place, when required on voyages over 24 hours.

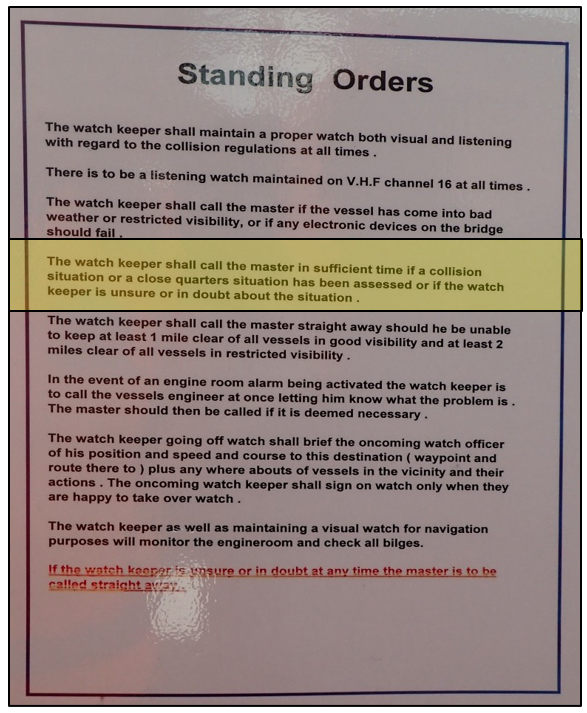

Access of Personnel to the Navigating Bridge and Avoiding Distraction

16. Companies provided information on established bridge access policies which were in place before the Costa Concordia accident. Identified best practice policies included the designation of Red, Amber and Green Conditions for the Bridge and Engine Control Room.

17. Such conditions are designed not only to ensure control of bridge access but to heighten alertness and minimise distractions, as navigational risk varies due to changing circumstances.

18. Companies also reported that they prohibit the use of mobile phones and other media or music devices on the bridge at any time, except as may be necessary for an emergency situation.

19. Typically such policies require the master and OOW to ensure that bridge organisation supports the increasing levels of team alertness and control of risks to safe navigation as conditions change from Green to Amber, Amber to Red or Green to Red.

20. The conditions and requirements for each condition, referred to above, are dependent on company policies and the ship’s trade and area of operation, however, in general:

1. Green is a condition for routine operations when the vessel is clear of pilotage waters and clear of any navigational situation requiring enhanced bridge organisation;

2. Amber is a condition requiring enhanced bridge organisation due to environmental, meteorological, operational or traffic risks, but clear of navigational danger; and

3. Red is a condition where a hazardous navigational situation exists due to meteorological conditions, technical deficiency or navigation in pilotage waters and in close proximity to other vessels or shore.

21. During Red and Amber conditions, procedures are in place to ensure that bridge access is restricted and distractions avoided such as phone calls to the bridge, not related to the immediate operation of the vessel.

Recommendations

22. It is recommended that bridge access control and bridge organisation policies are developed and harmonised to ensure that unnecessary distractions are avoided and that enhanced vigilance is in place and not disrupted during hazardous navigational situations.

Voyage Planning

23. Companies confirmed compliance with the Guidelines for Voyage Planning (Resolution A.893(21)). Company procedures for areas covering voyage planning, the conduct of a passage and bridge watchkeeping were evaluated. It was clear that any deviation from a passage plan is required to be planned in accordance with the Guidelines.

24. An example policy included the guidance that “Despite the master’s/OOW’s experience, qualifications and authority, the situation must never arise, even in pilotage waters, where the plan only exists in the master’s/OOW’s head.”

Recommendations

25. The requirements of A.893(21) should be fully complied with and in addition the further guidance in the ICS Bridge Procedures Guide should be taken into account:

“If the OOW has to leave the passage plan…the OOW should prepare and proceed along a new temporary track clear of any danger. At the first opportunity, the OOW should advise the master of the actions taken. The plan will need to be formally amended and a briefing made to the other members of the bridge team.”

Bridge Team Management and Maritime Resource Management

26. Companies reported on established and implemented bridge team management principles and techniques. One example of best practice is an effective ‘Challenge and Response’ environment on the Bridge and in the Engine Control Room. Effective Maritime Resource Management ensures that individual errors can be identified and corrected by team management of the Bridge or Engine Room.

27. It is noted that the STCW Convention, as amended, now includes requirements for leadership and teamwork skills, as well as resource management.

Auditing of Operations

28. It was reported that Bridge Team audits are conducted periodically and also at random intervals by operational management and by external parties contracted by companies. This ensures that the company’s shore operational management monitors the effectiveness of their bridge operations and that there is also an independent assessment provided. These audits focus on leadership, teamwork and management for all stages of the voyage plan.

Command Development

29. Many companies have established ‘Command Development’ policies that are undertaken prior to a competitive promotion process for command positions. These policies provide trainee masters and potential masters with professional development, support and guidance to prepare them for the role of master on company vessels.

Command Assessment

30. In addition to preparing and selecting masters, companies also regularly assess their masters’ performance at fixed and random periodic intervals. The assessments ensure that procedures are followed and that professional development continues following a command appointment.

Damage Control Drills

31. Since the Costa Concordia accident, companies have assessed the adequacy of and in some cases increased the frequency of, damage control drills.

Distress and Urgency Messages

32. Companies have reviewed their procedures to ensure that if a situation develops on board with the potential to require external assistance there should be no hesitation in requesting such assistance (including the issuing of an Urgency or Distress call) or in increasing on board states of readiness.

Shore Crisis Management

33. Companies reviewed their procedures for the management of an incident ashore and in particular the procedures for shore support and contact provided by a company during and after an incident.

ICS Bridge Procedures Guide

34. The ICS Bridge Procedures Guide is acknowledged as the principal industry guidance on the subject, it is used by ships worldwide and is referred to in the footnotes of several IMO Conventions. The Guide attempts to bring together the good practice of seafarers with the aim of improving navigational safety and protection of the marine environment. The need to ensure a safe navigational watch at all times, is a fundamental principle of the Guide. It is also clear that to ensure the safety of the vessel an essential part of bridge organisation is adherence to correct procedures.

35. ICS advised MSC 91 that the Bridge Procedures Guide is currently under review with the fifth edition anticipated for publication in early 2014. The outcomes of the Costa Concordia investigation will be taken into account during the review process, as appropriate.

Action requested of the Committee

The Committee is requested to note the information provided and in particular the recommendations in paragraphs 7, 8, 13, 22 and 25 and take action as appropriate.