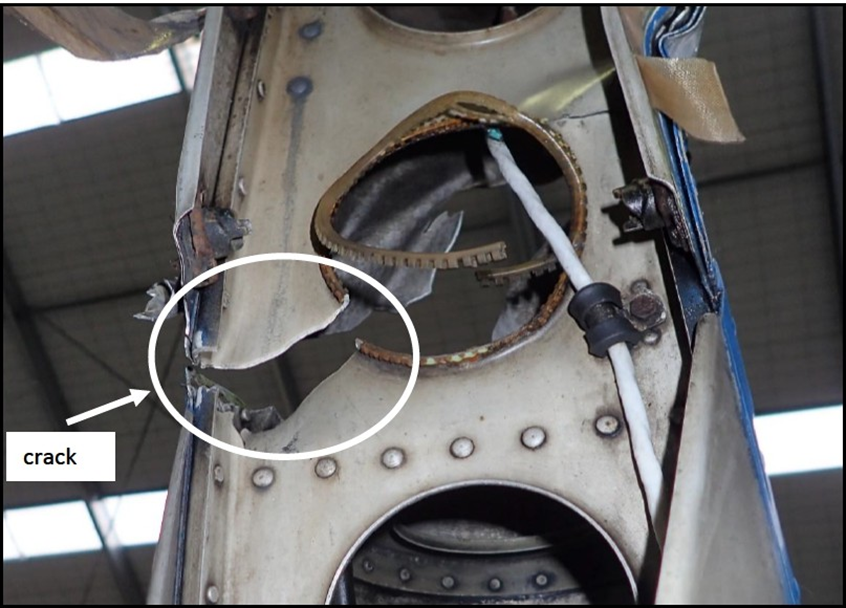

Examination

Supplied to DTA for analysis were the two primary halves of the fracture, labelled 17-004 E#8a and 17-004 E#8b. These samples will be referred to as 8a and 8b for the purposes of this report. A third sample sectioned from 8a as part of the Quest Integrity investigation was also supplied.

Visual examination of the as-received fracture surfaces revealed the presence of vast areas of impact damage, oxide deposits and debris. Solvent cleaning was undertaken to remove as much of the surface contamination as practical. Initial visual examination indicated overload. The fracture faces consistently exhibited fractures at 45° to the structure with a rough appearance that is associated with ductile overload fractures. No fracture faces exhibited indications of fatigue cracking or brittle fracture.

Following visual examination, all fracture surfaces and surrounding areas of interest were optically examined under magnification. All fracture surfaces displayed similar ductile failure morphologies, consistent with fast fracture (overload). Despite the solvent cleaning efforts large areas remained concealed by oxides and debris, interspersed with scoring and smearing. No evidence of fatigue or pre-existing cracks was found.

The section of the structure was removed for SEM inspection. This section was selected for high magnification SEM analysis as it contains fastener holes, tight radii, and other stress raisers, which are possible crack initiation sites.

SEM analysis microscopy showed consistent overload morphology at higher magnifications. On much of the fracture face feature definition was diminished due to widespread surface corrosion and damage. There were no obvious fatigue progression or arrest marks on the fracture surface and no obvious crack origin.

Discussion

Inspection of the fracture surfaces from the tail fin of ZK-IED was conducted from low to high magnification utilising magnifying eyepieces, a Leica M165 macroscope and SEM. Optical examination did not suggest there were any pre-existing cracks or fatigue cracking that had contributed to the failure of the component.